On the prehistoric plains of Australia shone a golden age for giant flightless birds. There was the “Demon Duck of Doom” that lived around 15 million years ago in what is now the continent’s Northern Territory.

Now, we need to make room in our hearts for another: an absolute unit that, scientists have revealed, bore more than a passing resemblance to modern geese. Just, you know, significantly larger.

We’ve known about Genyornis newtoni for quite some time. The species, which died out around 45,000 years ago, was first described in 1913.

An imposing bird standing up to 2.25 meters (7.4 feet) tall and weighing up to 230 kilograms (510 pounds), Genyornis newtoni would have been a formidable presence in the grassland habitats it preferred across a vast swathe of the Australian continent.

But a new discovery suggests that we may have misinterpreted the bird.

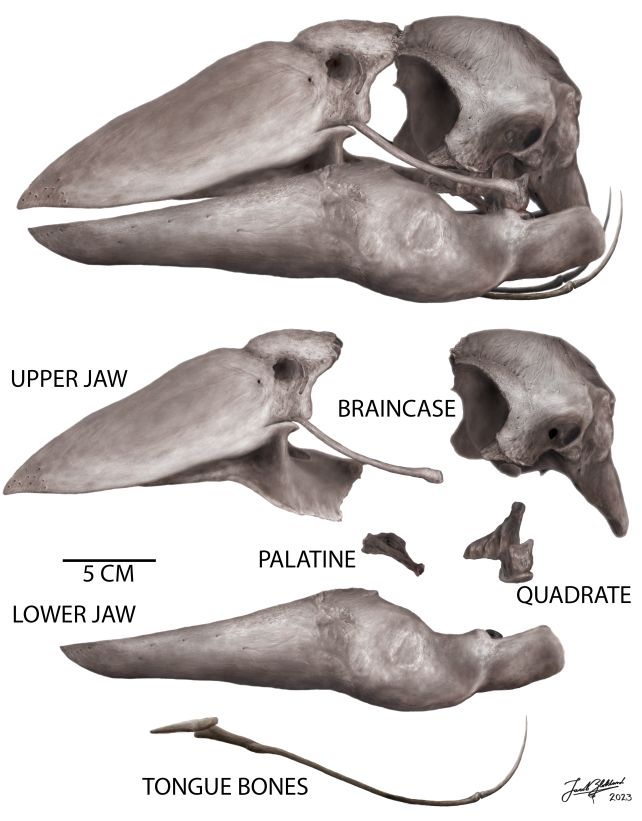

Paleontologists have uncovered a near-complete, articulated Genyornis newtoni skull. It’s only the second skull we’ve ever found for the species. The first was used for that 1913 species description, and it was in, not to be rude about it, absolutely terrible condition.

So now, for the first time, we’re actually getting a good look at the animal’s noggin – and what a spectacular noggin it was. The fossil reveals that Genyornis would have really stood out in a crowd, looking very different from other closely related birds.

It had a huge braincase, large jaws, and a triangular bony crest called a casque on its skull. In fact, some features of Genyornis newtoni’s skull were consistent, not with its closest relatives, but with early lineages of waterfowl diverging at the time.

Its beak looked similar to that of birds we see around us today, such as the Australian magpie goose (Anseranas semipalmata).

“Genyornis newtoni had a tall and mobile upper jaw like that of a parrot but shaped like a goose, a wide gape, strong bite force, and the ability to crush soft plants and fruit on the roof of their mouth,” says paleontologist Phoebe McInerney of Flinders University in Australia.

“The exact relationships of Genyornis within this group have been complicated to unravel, however, with this new skull we have started to piece together the puzzle which shows, simply put, this species to be a giant goose.”

The researchers performed scans of the fossil, and were able to create a detailed three-dimensional reconstruction. This reconstruction allowed for comparison with the skulls of other, living birds, to find out how the head of Genyornis would have functioned, and what it may have looked like, once more modestly clothed in flesh, skin, and feathers.

“The form of a bone, and structures on it, are partly related to the soft tissues that interact with them, such as muscles and ligaments, and their attachment sites or passages,” says paleontologist Jacob Blokland of Flinders University.

“Using modern birds as comparatives, we are able to put flesh back on the fossils and bring them back to life.”

This seems to have clinched it. The giant bird had several adaptations linked to aquatic habitats.

The structure of its ear was such that the canal would have been protected against water when Genyornis submerged its head, and the structure of its beak offered the same protection for its throat. The shape of the beak seems like it would also have been adept at grasping and tearing aquatic plants.

If this is the case, it could help explain why Genyornis went extinct, since the freshwater habitats it would have thrived in have since become salty, dramatically altering the ecosystem.

We’ll probably only learn more by further close analysis and hopefully finding more fossils, but it’s fantastic to finally learn the true identity of this remarkable species.

Just imagine it. It’s early dawn in the grassy swamp. A mist rolls across the landscape. As the first rays of sunlight spike over the horizon, life begins to stir. And, from the other side of the water, the birds start to call.

“HONK,” trumpets Genyornis. “HONK. HOOOOONK.”

Magnificent.

The research has been published in Historical Biology.