Before life on our planet exploded in diversity, Earth was once a ‘wormworld‘, dominated by wriggling tube-shaped creatures.

One of the earliest rulers of this ancient animal kingdom – a giant carnivorous worm – has now been found in fossil form.

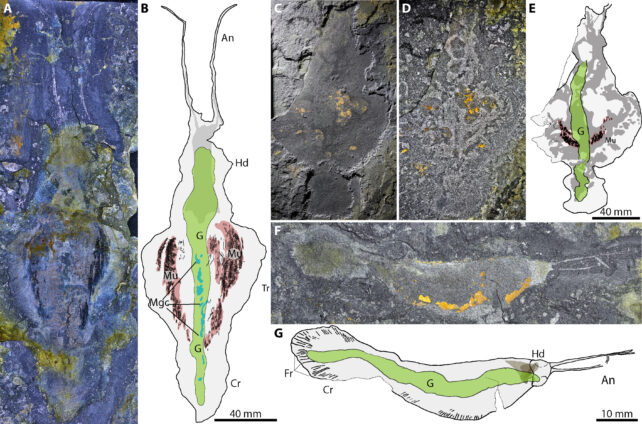

More than 518 million years ago, the roughly 30-centimeter-long critter would have been one of the largest existing swimming animals. Its relatively gigantic jaws, long antennae, and rippling fins would have made it a formidable enemy.

An international team of scientists, led by experts at the Korea Polar Research Institute (KPRI), have officially named the novel species Timorebestia koprii – the first part of which means ‘terror beasts’ in Latin.

“Timorebestia were giants of their day and would have been close to the top of the food chain,” says earth scientist Jakob Vinther from the University of Bristol.

“That makes it equivalent in importance to some of the top carnivores in modern oceans, such as sharks and seals back in the Cambrian period.”

The discovery of this species is based on 13 fossils found in North Greenland. In the digestive system of some fossils, researchers found evidence of food. Specifically, bivalved arthropods, called Isoxys.

Today, the living relatives of Timorbestia are known as arrow worms, and they are tiny compared to many other animals swimming in the ocean. Nevertheless, these worms are still important predators in the modern food web, picking on foundational prey like zooplankton.

The fossils of arrow worm ancestors can be traced back as far as 538 million years. That’s several million years older than known fossils of ancient arthropods, like insects, spiders, or crustaceans.

“Both arrow worms, and the more primitive Timorebestia, were swimming predators,” explains Vinther.

“We can therefore surmise that in all likelihood they were the predators that dominated the oceans before arthropods took off. Perhaps they had a dynasty of about 10–15 million years before they got superseded by other, and more successful, groups.”

These weren’t the only predators of the time to get knocked off their ecological thrones. The rapid evolutionary diversification of life during the Cambrian Explosion reshuffled the food web dramatically.

Some scientists suspect that the days of ‘wormworld’ set the stage for this critical turning point.

In a 2016 article, for instance, experts argued that the evolutionary breakthroughs achieved by ancient aquatic worms, “including novel strategies, behaviors, and physiologies,” increased the diversity of ocean ecosystems and “ultimately signaled the curtain call” of the Precambrian.

Timorebestia, for example, may have been an important evolutionary step in the development of internal jaws among predators. Ancient arrow worms, while closely related to Timorebestia, caught their prey not with their mouths but with external bristles.

“Over a series of expeditions to the very remote Sirius Passet in the furthest reaches of North Greenland… we have collected a great diversity of exciting new organisms,” says the field expedition leader Tae Yoon Park from the Korean Polar Research Institute.

“We have many more exciting findings to share in the coming years that will help show how the earliest animal ecosystems looked like and evolved.”

The study was published in Science Advances.