A popular and easy way to check whether a boulder is a meteorite or not, and what type of meteorite it is, was to accidentally delete invaluable information that was trapped within.

Using rare-earth magnets such as neodymium erases and overwrites the magnetic record trapped in ferromagnetic minerals in meteorites, scientists from MIT in the US and the University of Paris Cité in France have found. Since many meteorites that fall to Earth have significant iron content, it means we are losing important data on how magnetic fields in space have altered these meteorites over billions of years.

“Meteorites provide invaluable records of planet formation and evolution. Studies of their paleomagnetism have constrained accretion in the protoplanetary disk, thermal evolution and differentiation of planetesimals, and the history of planetary dynamos.

“Nevertheless, the potential of these magnetic records to advance the field of planetary science is severely hampered by a widely used technique: the application of handheld magnets to aid in meteorite classification.” Write a team led by MIT planetary scientist Foteini Vervelidou.

“Touching a meteorite with a magnet results in the almost instantaneous destruction of its magnetic record.”

Exposure to a magnetic field can have an interesting effect on minerals. As a rock chunk forms, the crystals in magnetic minerals can align with the magnetic field and in some cases become magnetized themselves, providing a record of the strength and orientation of the magnetic field that caused it.

Here on Earth, studying these records is known as paleomagnetism, and scientists use them to understand the history of the Earth’s magnetic field and how it has evolved and changed over time. The ground beneath our feet abounds with such records, and we have learned much about our ever-changing homeworld.

Other rocky worlds are expected to keep similar records, but our access to them is obviously much more limited. Mars, for example, is of great interest. The Earth’s magnetic field is generated by a dynamo: a rotating, convective, conductive fluid deep within the planet that converts kinetic energy into magnetic energy.

Mars currently has no active dynamo, and the disappearance of its global magnetic field is a mystery. Ancient rocks from Mars may reveal more about the time in Mars’ history when there was an active dynamo; and ancient rocks from Mars occasionally, rarely, find their way here to Earth.

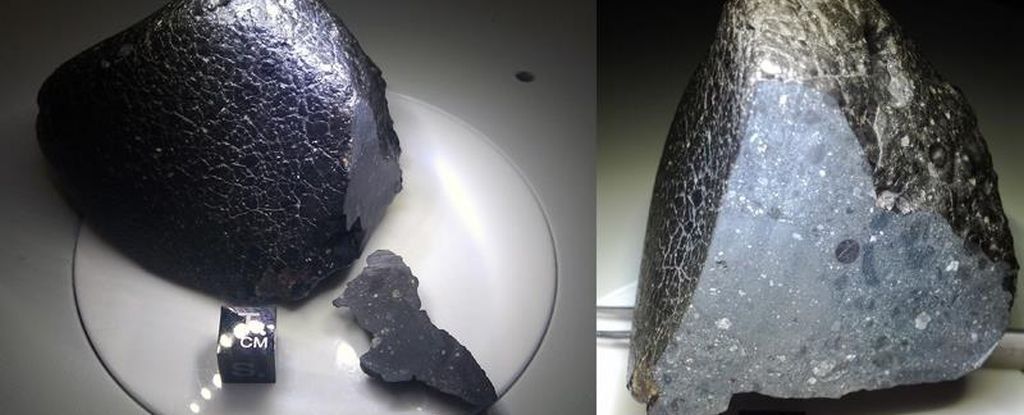

The meteorite Black Beauty, also known as Northwest Africa 7034, recovered from the desert sands of Morocco in 2011, is a famous example. It’s one of the oldest Meteorites from Mars on Earth and contains fragments dated up to 4.4 billion years old – when the solar system and the planets in it were babies.

Scientists thought it was supposed to keep a record of the Martian dynamo at the time, but when they checked magnetic records in boulders, they found nothing – not a trace. Any magnetic records of Mars remaining in NWA 7034 after its journey to Earth have been obliterated by magnets used by meteorite hunters to verify their finds.

This phenomenon has been observed in many meteorites, but no one had done a systematic study of how it occurs. So Vervelidou and her colleagues performed a multi-step analysis, combining numerical modeling, remagnetization of terrestrial basalt with handheld magnets, and an examination of 9 fragments of the parent meteorite that produced NWA 7034.

First, they calculated the magnitude of a magnetic field around a hand-held magnet and the effect that field would have on rocks of different sizes. Next, they tested the results of their calculations on lumps of earthen basalt and measured the magnetization in the rock before and after exposure to a neodymium magnet.

Many of the chunks became fully demagnetized after exposure to the hand magnet, and others were consistent with the partial demagnetization observed in meteorite chunks.

The 2014 study of NWA 7034 mentioned above indicated that the rock had been wiped away, but the other fragments of the parent meteorite may still have contained traces of the original magnetic record. So the next step in the research was to test these other fragments. Unfortunately, Vervelidou and her team found that none of the fragments contained a trace of these records. They had all been completely erased.

However, research has shown that the magnetic disturbance is progressive and follows a similar demagnetization curve. So future scientists studying the magnetization of meteorites have a guide to how deep the demagnetization can go, allowing them to find samples that contain fossilized magnetic fields, either from planetary processes, or the solar system itself.

There are now techniques that can help identify meteorites without destroying the sensitive internal information.

“The use of magnetic susceptibility gauges has been shown in many studies to be an accurate and non-destructive method of meteorite identification and classification. Not only can they be used to distinguish between meteorites and earth rock, but they can also be used to distinguish between different types of meteorites. ” write the researchers.

“We continue to hope that more paired rocks from NWA 7034 and new Martian meteorite finds free from the effects of magnet remagnetization will become available in the near future.”

The research was published in JGR planets.