A medieval astronomical instrument discovered entirely by accident has turned out to be a powerful record of cross-cultural scientific collaboration.

The brass astrolabe dates back to 11th century Spain – but was subsequently engraved with annotations and amendments over the centuries, in multiple languages, as changing owners adapted and updated it for their own use.

The object is, therefore, not just a rare artifact, but almost unique: a palimpsest that records changing ideas and needs of its users as the world and context changes.

“This isn’t just an incredibly rare object. It’s a powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews, and Christians over hundreds of years,” says historian Federica Gigante of the University of Cambridge, who rediscovered the astrolabe and its inscriptions in an Italian museum in Verona.

“The Verona astrolabe underwent many modifications, additions, and adaptations as it changed hands. At least three separate users felt the need to add translations and corrections to this object, two using Hebrew and one using a Western language.”

Astrolabes are instruments that chart the heavens, and have been in use for many hundreds of years. They consist of a map of the sky with rotating parts that allow users to calculate their position in time and space – a powerful tool, not just for navigation, but for astronomy, and astrology as well.

They first emerged in Ancient Greece, but only through development in the Islamic world did they reach their full versatility.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” allowfullscreen>

That versatility is on full display with what Gigante calls the Verona astrolabe – because it was discovered in the collection of the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo in Verona, likely obtained as part of the collection of noble and art collector Ludovico Moscardo, who lived in Verona in the 17th century.

Gigante, who specializes in artifacts from the Islamic world in the early modern period, noticed a newly uploaded photo of the astrolabe on the museum’s website, and reached out to them to find out more about it.

“The museum didn’t know what it was, and thought it might actually be fake. It’s now the single most important object in their collection,” she says.

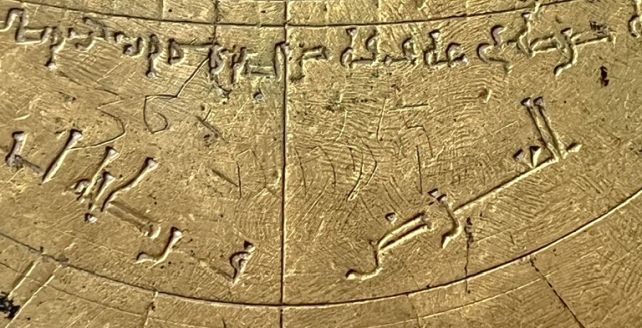

“When I visited the museum and studied the astrolabe up close, I noticed that not only was it covered in beautifully engraved Arabic inscriptions but that I could see faint inscriptions in Hebrew. I could only make them out in the raking light entering from a window. I thought I might be dreaming but I kept seeing more and more. It was very exciting.”

Working out the provenance of the instrument involved carefully studying its features and comparing them to other astrolabes. The style of the astrolabe, the engraving on the back, and the style of the calligraphy, are consistent with other astrolabes made in Al-Andalus, Islamic Spain, in the 11th century.

This is supported by the positions of the star pointers, which are consistent with an astrolabe made by Ibrāhīm ibn Saʿīd al-Sahlī in the Spanish municipality of Toledo in 1068 CE. This suggests that it was based on star coordinates used in the late 11th century.

As for the engravings on the object, they speak of a rich cultural history. Some of the Arabic inscriptions are Muslim prayer lines and prayer names; since astrolabes could be used for timekeeping, this suggests that at least one owner used the artifact for prayer.

Another Arabic inscription reads “for Isḥāq” and “the work of Yūnus”. Gigante believes this inscription was added some time after the astrolabe was made. It’s impossible to tell who Isḥāq and Yūnus might be, or if indeed Yūnus was the one who made the astrolabe, but the two names in English are Isaac and Jonas.

In medieval Spain, there was a sizable Sephardic Jewish community who spoke Arabic. This inscription could mean that the astrolabe spent some time there, too.

The Hebrew inscriptions include translations for astrological constellations, which is also very telling, Gigante says.

“These Hebrew additions and translations suggest that at a certain point the object left Spain or North Africa and circulated amongst the Jewish diaspora community in Italy,” she explains, “where Arabic was not understood, and Hebrew was used instead.”

Finally, someone, at some point, has scratched latitude corrections on both sides of the astrolabe in Western Arabic numerals (the ones we use today), probably for a Latin or Italian speaker. Interestingly, though, some of the corrections appear to be wrong.

Many objects that make their way to us down the centuries have many tales that we’ll never know. That’s also the case for the Verona astrolabe – but its scratchings and engravings offer us a window into its history that very few artifacts can offer. It’s a spectacular discovery that speaks to years, if not centuries, of cultural mixing and exchange.

“This object is Islamic, Jewish, and European, they can’t be separated,” Gigante says.

The research has been published in Nuncius.