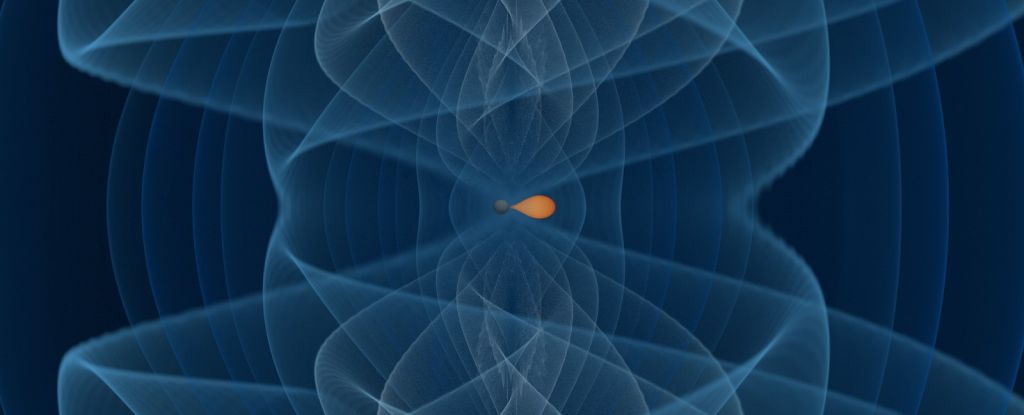

A gravitational wave detected in May of last year has given us a type of cosmic collision we’ve never seen before.

One of the masses involved was a neutron star. So far, so normal.

But we don’t know what the other object was. That’s because it sits firmly in a niche known as the lower mass gap – the seemingly rare bodies with masses somewhere between the chonkiest neutron stars and the titchiest black holes.

It’s the first time we’ve seen a gravitational wave event involving a neutron star and a mass gap object, and although we aren’t much closer to knowing what the latter actually is, the discovery excitingly suggests that these elusive mystery blobs could be common in the galaxy.

“While previous evidence for mass-gap objects has been reported both in gravitational and electromagnetic waves, this system is especially exciting because it’s the first gravitational-wave detection of a mass-gap object paired with a neutron star,” says astrophysicist Sylvia Biscoveanu of Northwestern University in the US.

“The observation of this system has important implications for both theories of binary evolution and electromagnetic counterparts to compact-object mergers.”

Neutron stars and stellar-mass black holes belong to the same class of cosmic object. They’re what’s left of massive stars that have reached the ends of their lives and gone supernova. The outer material of the star explodes violently into space; but the core in the center of the star – no longer supported by the outward pressure of fusion – collapses down into an ultradense object.

What determines the outcome is mass. Stars with a starting mass of about eight to 30 times the mass of the Sun end up as neutron stars. Once most of the stellar material has been ejected, the collapsed core will have a mass of up to 2.3 solar masses packed into a sphere just 20 kilometers (12 miles) across.

Stellar black holes form in the collapse of stars with far more mass, leaving highly-concentrated pockets of material that tend to range from around five to a dozen or so solar masses.

Here’s where it gets interesting: we’ve detected very few objects between 2.3 and five solar masses. And of those we have detected, it’s unclear whether we’re looking at a small black hole or a big neutron star.

Since the region between the heftiest neutron stars and lightest black holes is curiously devoid of detections, scientists refer to it as the lower mass gap (to differentiate it from the black hole upper mass gap).

Gravitational wave detections are flying thick and fast these days, and astronomers are using them to understand black holes; their number and mass distribution gives us an idea of how many there are out there, and how they form and grow.

The lower mass gap is a mystery that scientists have been hoping gravitational waves would shed some light on. In 2020, the first detection came in of a merger between a black hole and a mass gap object, something that clocked in at 2.6 solar masses.

The new detection, called GW230529, was made in May 2023. By analyzing the gravitational wave signal, the LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA collaborations were able to determine that one of the objects involved was between 1.2 and 2 solar masses. That’s fairly solidly in the neutron star range.

The second object, however, was between 2.5 and 4.5 solar masses. That’s firmly in the mass gap. The researchers believe that it’s probably a tiny black hole; there’s no way of knowing with the current data, but it exceeds the theoretical upper limit for neutron star mass, so it’s the most plausible explanation at this time.

But it’s the fact of the discovery itself that is most exciting, and what it means for future detections.

“Before we started observing the Universe in gravitational waves, the properties of compact objects like black holes and neutron stars were indirectly inferred from electromagnetic observations of systems in our Milky Way,” says astrophysicist Michael Zevin of the Adler Planetarium in the US.

“The idea of a gap between neutron-star and black-hole masses, an idea that has been around for a quarter of a century, was driven by such electromagnetic observations. GW230529 is an exciting discovery because it hints at this ‘mass gap’ being less empty than astronomers previously thought, which has implications for the supernova explosions that form compact objects and for the potential light shows that ensue when a black hole rips apart a neutron star.”

The LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA gravitational wave detectors have all been undergoing maintenance, and recent upgrades have dramatically improved detection sensitivity. The observing run is set to resume on 10 April 2024; we’re anticipating some more juicy black hole discoveries in the near future.

The research can be read on the LIGO website.