Even in death, NASA’s Ingenuity helicopter is helping us learn about Mars.

The small aircraft met the demise of its main mission on 18 January 2024, after nearly three epic years of flitting around in the thin Martian atmosphere, like the piece of engineering marvel that it is.

Its final flight was both sad and triumphant: the helicopter was only planned to fly five times across a total of 31 days, yet managed a jaw-dropping 72 flights over the surface of the red planet.

The data collected during these flights told us a lot about Mars, and how to navigate the challenges it presents for human exploration. And now, engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and defense contractor AeroVironment are finishing up their investigation.

This, too, is exciting: it’s the first aircraft accident report ever conducted for another planet, the distance to which presented some unique challenges.

“When running an accident investigation from 100 million miles away, you don’t have any black boxes or eyewitnesses,” says cybernetics engineer and roboticist Håvard Grip of JPL.

“While multiple scenarios are viable with the available data, we have one we believe is most likely: Lack of surface texture gave the navigation system too little information to work with.”

Ingenuity’s 72nd, and final, flight started normally. The little helicopter was supposed to just lift up, hover for a bit, take some photos, and land again – a routine outing to do a little reconnaissance and test the helicopter’s systems.

The first part went fine. Ingenuity powered up its rotors, lifted off, hovering at 12 meters (40 feet) for about 20 seconds while it took some photos.

Its descent is where things went haywire, but it’s not entirely clear how. About 1 meter from the ground, Ingenuity lost contact with the Perseverance rover, which acts as a communications relay to Earth.

The images that came back in after communications were reestablished showed Ingenuity on the ground with its rotors damaged beyond repair.

After examining all the available evidence, engineers here on Earth believe that they have determined the root cause of the crash.

In order to navigate effectively, the helicopter was equipped with a downward-facing camera that takes images of the Martian surface at a rate of 30 frames per second.

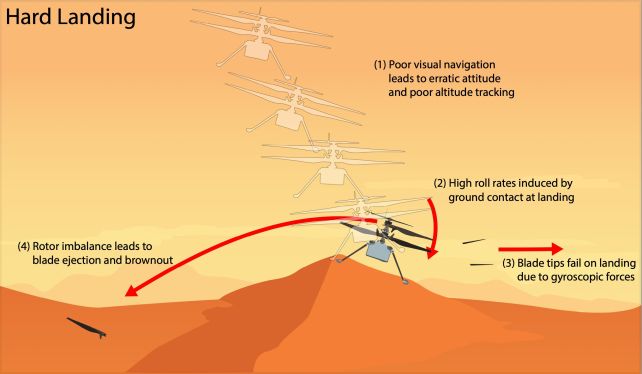

The navigation system looks at the timestamp of each image to know when it was taken, and uses this information to compare what the camera sees based on what it should have been seeing at that time. If this doesn’t stack up, the helicopter makes adjustments to its position, velocity, and attitude.

In order to do this, the camera picks out features on the surface of Mars, such as pebbly textures or rocks (there are a lot of rocks on Mars). But when the helicopter took off for its 72nd flight, it was in a sandy region of the Jezero crater relatively devoid of surface features.

As we learnt in May 2021, when the helicopter suddenly spun out of control, the seamless operation of this camera was crucial to Ingenuity’s ability to gauge how fast it should be traveling. On that occasion, Ingenuity recovered.

In January 2024, the camera could find no surface features to track, meaning that Ingenuity couldn’t determine how fast it should be descending. It hit the ground much faster than it should have. This in itself wasn’t the problem; it was what happened next.

According to NASA’s reconstruction, the hard impact caused the helicopter to pitch and roll, causing stress to all four rotors that made them snap at their weakest point, about a third of the length from the tip of each blade. This damage made the rotor system vibrate, which ripped out one of the blades entirely at its root, overloading the helicopter’s electronics, and cutting communications to compensate.

The little helicopter that could will fly no more. But its other instruments are still operational, which means we still receive data from it, both about the weather on Mars, and its own equipment. Both kinds of data will benefit the planning of future Mars exploration.

“Because Ingenuity was designed to be affordable while demanding huge amounts of computer power, we became the first mission to fly commercial off-the-shelf cellphone processors in deep space,” says engineer Teddy Tzanetos of JPL.

“We’re now approaching four years of continuous operations, suggesting that not everything needs to be bigger, heavier, and radiation-hardened to work in the harsh Martian environment.”

The technical report on the crash should be released in the coming weeks.