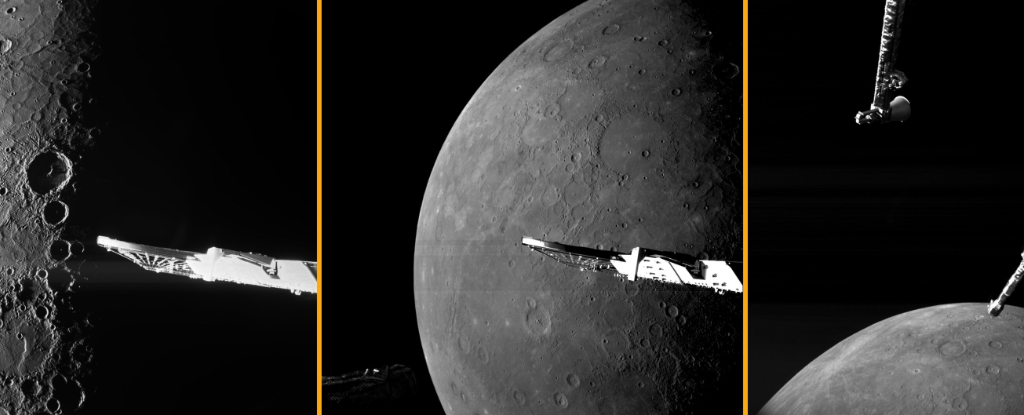

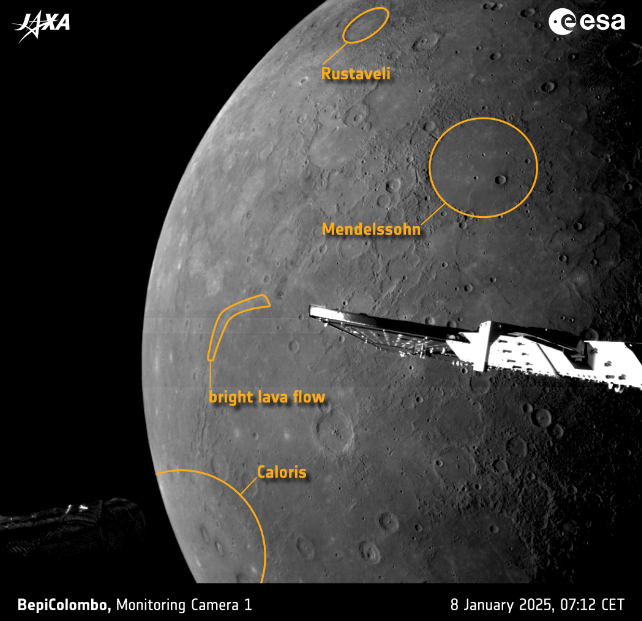

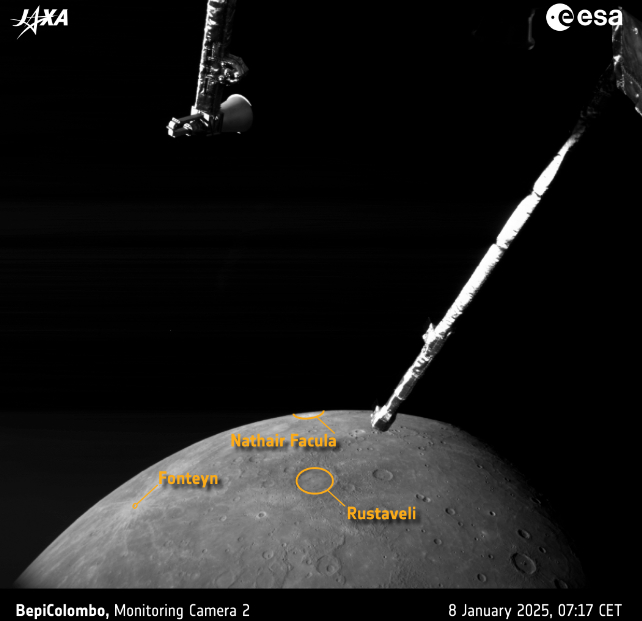

From just 295 kilometers above Mercury‘s surface, ESA’s BepiColombo transfer probe has captured stunning close-up images while on its final flyby of the tiny, sunbaked world.

The photos represent a planet in the grip of extremes, revealing detailed views of permanent darkness bordered by crater rims blasted by endless daylight. Within those shadows, it’s thought, sits a layer of ice, preserving clues that could help us better understand Mercury’s past and potentially its future.

“In the next few weeks, the BepiColombo team will work hard to unravel as many of Mercury’s mysteries with the data from this flyby as we can,” ESA (European Space Agency) Project Scientist Geraint Jones said at the agency’s annual press briefing on January 9.

Having completed its set of gravitational assists, the mission will enter its next phase, readying itself for data collection in 2027.

“BepiColombo’s main mission phase may only start two years from now,” Jones explained,” but all six of its flybys of Mercury have given us invaluable new information about the little-explored planet.”

Mercury is a peculiar sphere of rock, as far as planets go. Barely larger than our own Moon, it orbits within a cosmic whisker of our Sun at an average distance of roughly 58 million kilometers (36 million miles).

Scoured by radiation and eroded by solar wind, its atmosphere is a miserable film of gas constantly regenerated as meteorites and plasma tear into its hide.

At high noon, temperatures can reach a scorching 430 degrees Celsius (more than 800 degrees Fahrenheit). Without an appreciable atmosphere to spread and trap heat, hidden crevices and the predawn chill can reach lows of minus 180 degrees Celsius.

Beneath the surface there are secrets we can only guess at. Mechanisms responsible for a mysterious magnetic field. A bounty of carbon that could take the form of a thick layer of diamond. Some kind of activity that could be causing the planet to slowly shrink over time.

Launched in October 2018, BepiColombo aims to collect data on Mercury’s magnetism, gaseous exosphere, and surface features that could help explain these oddities and more.

On the way, its monitoring cameras have sent glorious snapshots of not only the innermost planet’s surface, but the cloudtops of Venus as it passed by.

Together with these latest images, astronomers have amassed evidence of a world slowly darkened by time, with evidence of occasional rejuvenation by monumental impacts and a history of volcanic eruptions.

In one image a feature called the Nathair Facula preserves signs of Mercury’s largest known volcanic explosion, still marked by a vent some 40 kilometers across in its very center.

Nearby sits Fonteyn crater, shining with relative youth having formed a mere 300 million years ago.

In 2026, the Bepicolombo Mercury Transfer Module will return to Mercury once again to release the ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, aiming to spend 2027 collecting data from their individual altitudes and orientations above the planet.

Neither will come within 480 kilometers of the planet’s surface, making these the closest visuals of Mercury we’ll see for a while.

Nonetheless, our picture of the hellish world is about to become a lot more detailed as BepiColombo settles in to do the job it came for.