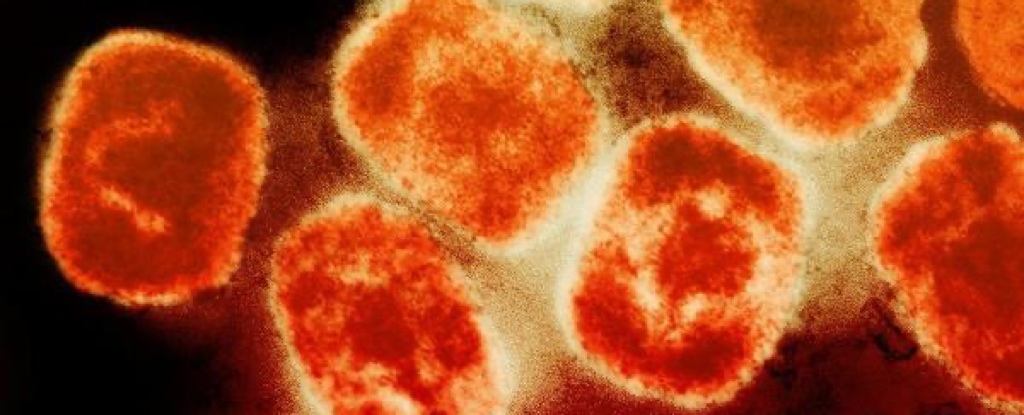

Mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is a viral infection that can be prevented with just a single dose of an existing vaccine, a new study finds.

This discovery could help slow the tide of the global mpox outbreak, which was declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization back in July 2022.

At the time, the WHO recommended that targeted use of second- or third-generation smallpox vaccines could help, but there has been little clinical or real-world data on the effectiveness of this approach since. Smallpox is a viral illness related to mpox that can be prevented with a vaccine.

New drug and vaccine development can take time and money that could be otherwise spent on rollout, so it’s great news that an existing vaccine could be effective at preventing mpox.

Observational studies conducted since the WHO announcement have suggested the modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) vaccine could be anywhere from 36 to 86 percent effective for mpox prevention.

The team behind the new study, led by public health physician Christine Navarro from Public Health Ontario and the University of Toronto, acknowledge observational data are prone to bias, which can lead to misleading or inaccurate results.

But in this urgent situation, where mpox infections are once again rising globally, and “the most dangerous” strain yet spreading across Africa, observational findings – where a study relies on an existing intervention to test an hypothesis – can offer much-needed solutions quickly.

So the researchers applied the design principles of randomized trials – the gold standard for testing drug efficacy – to an analysis of observational data. The technique is called target trial emulation, and it can estimate the causal effect of a vaccine while minimizing biases.

The 3,204 MVA-BN vaccinated men in the study, all from Ontario in Canada, had received one dose before exposure to mpox, which reached Ontario sometime between June 2022 and November 2022.

This group was matched to 3,204 men who had not received the vaccine, for comparison. If any of the men in this group became vaccinated during the study period, another unvaccinated man was added – so that nobody was denied access to a vaccine, they were simply studied as controls while they were ‘in the queue’.

Across the study period, 71 mpox infections were diagnosed, with 21 of those from the vaccinated group, and 50 from the unvaccinated group.

This sets the estimated effectiveness of a single dose of the vaccine at 58 percent.

They also found MVA-BN was not associated with a reduced rate of mpox infection during the first 14 days post-vaccine, most likely because it was too soon for the body to develop an adequate antibody response.

And while it’s no surprise that it would take a while for a vaccine to work its magic, this finding adds further support for the vaccine being the specific cause of reduced mpox infections among the vaccinated cohort.

“Although MVA-BN is approved in Canada as a series of two doses 28 days apart, Ontario initially employed a dose sparing strategy such that vaccine candidates could only receive one dose owing to concerns about limited vaccine supply,” the authors write.

A two-dose program was implemented in Ontario at the end of September 2022, but too few participants had received that second dose for the researchers to assess its effectiveness in the current study.

“Our findings strengthen the evidence that MVA-BN is effective at preventing mpox infection and should be made available and accessible to communities at risk,” the authors conclude.

This research is published in the British Medical Journal.