Previously considered an airless ball, an Earth-sized world orbiting a red dwarf some 40 light-years away may have an atmosphere after all.

New observations of planet b in the TRAPPIST-1 system reveal that the rocky world is more complex than we thought, affirming the challenges of drawing solid conclusions based on a narrow band of spectral information.

In stark contrast with a paper released last year that determined the exoplanet was likely to be bare and barren, new data obtained using JWST suggest that TRAPPIST-1b is either roiling with geological activity, or possibly shrouded in a thick atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide.

“The idea of a rocky planet with a heavily weathered surface without an atmosphere is inconsistent with the current measurement,” says astronomer Jeroen Bouwman of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

“Therefore, we think the planet is covered with relatively unchanged material.”

That means unchanged by stellar and space weathering processes, suggesting that the surface of TRAPPIST-1b is very young, only up to 1,000 years old. In turn, that implies activity, such as magmatic resurfacing – hinting at ongoing geology inside the exoplanet.

In 2017, astronomers reported that they’d found a star around which seven exoplanets were orbiting. Although the exoplanets are a bit closer to the star than the planets of the Solar System, the star TRAPPIST-1 is a red dwarf – cooler and dimmer, which in turn means the system’s habitable zone is closer to its sun.

This raised hopes that one of the TRAPPIST-1 worlds might be habitable. It also gave us several exoplanets that may be analogous to worlds within the Solar System, with comparable sizes and densities to Earth, Venus, and Mars.

TRAPPIST-1b is too close to its star to be habitable, but astronomers hope it can teach us about how other planetary systems form and evolve.

“Planets orbiting red dwarfs are our best chance of studying for the first time the atmospheres of temperate rocky planets, those that receive stellar fluxes between those of Mercury and Mars,” says astronomer Elsa Ducrot of the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA).

“The TRAPPIST-1 planets provide an ideal laboratory for this ground-breaking research.”

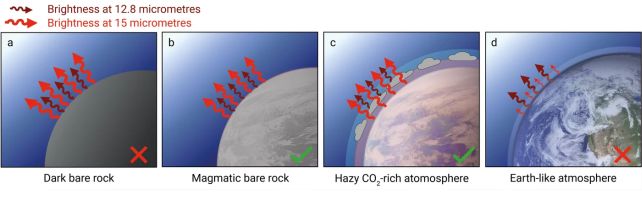

The first data from JWST dealt a blow to that idea. It was based on just one infrared wavelength – 15 microns – which is strongly absorbed by carbon dioxide. The strong 15-micron signature suggested that no carbon dioxide was present.

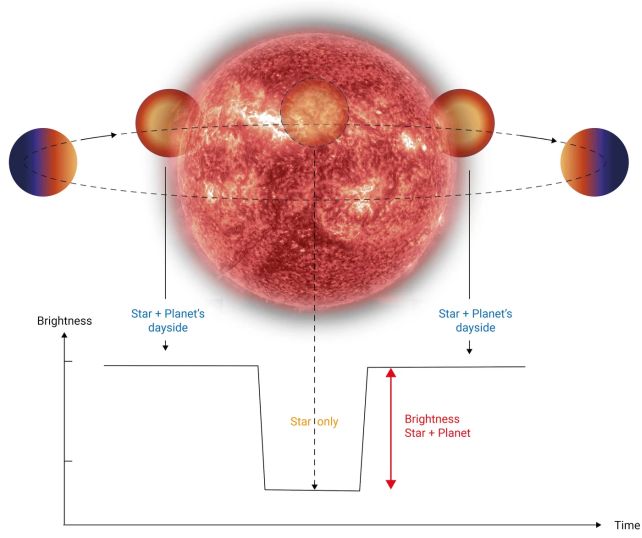

In order to investigate in more detail, the researchers took further JWST observations in the 12.8-micron wavelength to measure the temperature of TRAPPIST-1b as it made repeated orbits of its star. As the exoplanet moves in front, around to the side, and behind the star, the changing light reveals how much of the infrared light is emitted by the exoplanet, giving astronomers the tools to measure the temperature distribution across the exoplanet’s surface.

Then, they compared their observations against different models to try to figure out what they were seeing. In contrast to the 15-micron analysis, which found a bare, gray surface, the research team found the 12.8-micron observations more consistent with a bare surface covered in mineral-rich volcanic rock.

This could indicate that TRAPPIST-1b has tectonic or volcanic activity, or that the gravitational tugging of the star and the other exoplanets in the system are stretching and squeezing TRAPPIST-1b to keep its interior hot and molten.

The other interpretation of the data is an atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide. This can be reconciled with the 15-micron observations by the presence of a haze resulting in a phenomenon known as thermal inversion, whereby the carbon dioxide emits 15-micron light rather than absorbs it.

“These thermal inversions are quite common in the atmospheres of Solar System bodies, perhaps the most similar example being the hazy atmosphere of Saturn‘s moon Titan,” explains astronomer Michiel Min from the Netherlands Institute for Space Research.

“Yet, the chemistry in the atmosphere of TRAPPIST-1b is expected to be very different from Titan or any of the Solar System’s rocky bodies and it is fascinating to think we might be looking at a type of atmosphere we have never seen before.”

Which, if any, of these scenarios is occurring on TRAPPIST-1b is going to take a lot more digging to reveal. But the study highlights just how difficult it is to figure out what’s happening on other worlds, beyond the Solar System.

The team’s research has been published in Nature Astronomy.