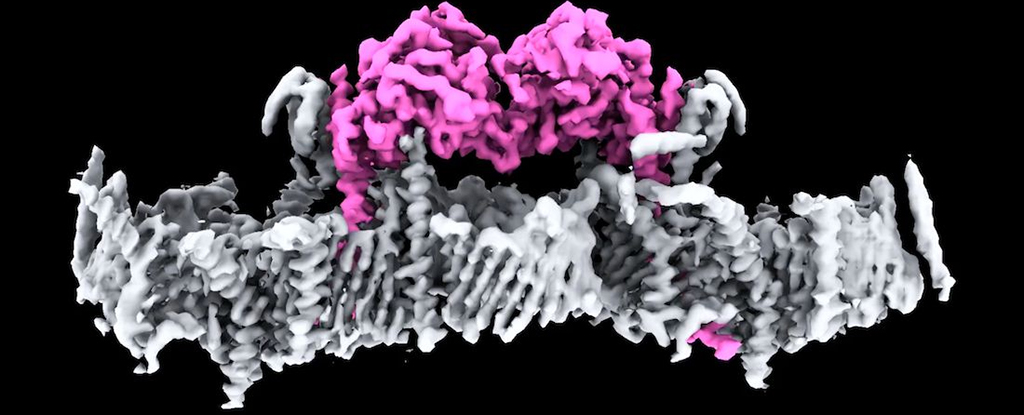

Researchers have unveiled the first real look at a mitochondrial protein strongly linked to Parkinson’s disease, revealing key details in how its malfunction might play a critical role in the disease’s progress.

Scientists have known for more than two decades that mutations in the gene for a protein called PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) can trigger early-onset Parkinson’s, but the mechanisms at play have remained a mystery.

A team of scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI) in Australia used advanced imaging technology to not only determine the structure of PINK1, but to show how the protein attaches to cellular power houses and how they are activated.

“This is a significant milestone for research into Parkinson’s,” says WEHI medical biologist David Komander.

“It is incredible to finally see PINK1 and understand how it binds to mitochondria. Our structure reveals many new ways to change PINK1, essentially switching it on, which will be life-changing for people with Parkinson’s.”

The PINK1 protein is an important maintenance worker in the body. In healthy mitochondria, the protein passes through the outer and inner membranes, where it sinks out of sight.

In mitochondria that have broken down, the protein is forced to pause half way through, tagging the power house for deletion through a series of processes that release a chemical signal called ubiquitin. When mutations prevent PINK1 from doing its job, dysfunctional mitochondria aren’t cleared.

Brain cells are particularly energy hungry, making the replacement of inefficient power units vital in order to prevent the neurodegeneration that triggers conditions like Parkinson’s disease.

Here, the team used techniques including cryo-electron microscopy and mass spectrometry to study PINK1 and mitochondria close-up, finding their attachment is based on a specific protein complex called TOM-VDAC.

It’s still early days for this research, but if treatments to repair the functionality of the protein can be developed, that may then give us a way of reducing the risk of Parkinson’s or slowing its progress.

“This is the first time we’ve seen human PINK1 docked to the surface of damaged mitochondria and it has uncovered a remarkable array of proteins that act as the docking site,” says biochemist Sylvie Callegari, from WEHI.

“We also saw, for the first time, how mutations present in people with Parkinson’s disease affect human PINK1.”

Parkinson’s is a complex disease, with undoubtedly numerous contributing factors. Yet by identifying the mechanisms behind proteins like PINK1, researchers move closer to understanding what the many causes have in common.

The research has been published in Science.