Scientific detective work has uncovered a truly harrowing incident of shark-on-shark crime in the waters of Bermuda.

There, a pregnant porbeagle was slain and devoured – and we only know her fate thanks to a satellite tag with which she had been equipped. The strange temperature data overwhelmingly led to just one explanation.

“I couldn’t believe it when I got the data from our pregnant porbeagle shark’s satellite tag,” marine biologist Brooke Anderson of Arizona State University told ScienceAlert.

“I kept trying to think of alternative explanations for the increase in temperature at depth, but all signs pointed to the same conclusion…that our pregnant female porbeagle had to have been eaten by an even larger shark.”

Porbeagles (Lamna nasus) are large mackerel sharks that can be found widely distributed around the world, but their numbers are in a worrying decline. Porbeagles are a popular target for recreational fishing, but they are also targeted in commercial fishing, and end up as bycatch in the same.

These sharks can grow up to 3.7 meters (12.1 feet) in length, weigh up to 230 kilograms (507 pounds), and live long lives up to several decades. But, like other mackerel sharks, they are oviviparous, meaning that their young first incubate in eggs inside their mothers, before hatching, still in utero, to complete their gestation. They are born live after about eight or nine months.

Female porbeagles don’t start reproducing until they’re around 13 years old, and then have litters of up to around four pups every year or two.

This slow reproductive cycle makes them particularly vulnerable to population decline, especially when faced with multiple threats. To figure out how to protect these vulnerable animals, Anderson and her colleagues monitored the species using satellite tags that record the sharks’ movements and behavior.

The tags used are a kind called pop-off tags. They record information such as temperature, water depth, and rough location for a period of time, storing the data until they ‘pop off’, detaching from the shark and floating to the surface.

After three days of no changes in water pressure, the tag assumes that it is no longer attached to the shark, and transmits all its stored data to the waiting scientists. In addition, a fin-mounted tag on the shark sends more accurate location data when the fin rises above the water’s surface.

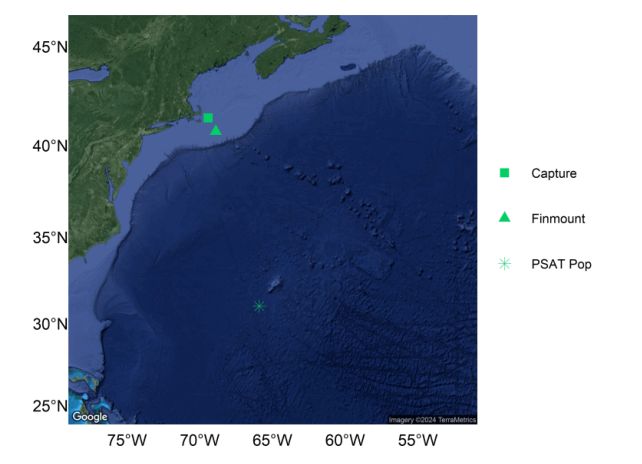

The pregnant porbeagle, measuring 2.23 meters, was tagged on 28 October 2020. On 3 April 2021, the researchers started receiving data from the pop-off tag.

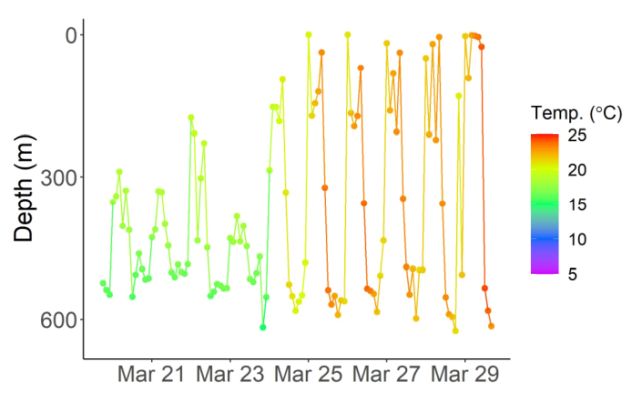

That data was odd. Up until 24 March 2021, the porbeagle seemed to be behaving pretty normally. From late December, she spent her time in the North Atlantic Ocean, diving to between 100 and 200 meters at night, and 600 to 800 meters during the day, at temperatures ranging between 6.4 and 23.52 degrees Celsius (43.5 and 74.3 degrees Fahrenheit).

On March 24, the tag had recorded similar depth ranges in the same place, between 150 and 600 meters. But the temperature was significantly higher, around 5 degrees Celsius higher than the surrounding water.

The only possibility, Anderson and her colleagues concluded, was that the porbeagle had been eaten by a predator, likely a white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) or a shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus), both of which are partially endothermic; that is, the movement of their muscles generates warmth as the shark swims.

The tag probably spent some time in the predator’s digestive tract; when it was excreted out, it rose to the surface of the ocean, from whence it began transmitting 3.5 days later.

“It’s highly unlikely that the temperature increase was due to the shark moving into a warmer water body based on all the other data we have, such as the change in diving behavior, the premature release of the pop-off satellite tag, and the fact that we never received any other locations from the finmount satellite tag,” Anderson explained.

“All this other evidence still points to a predation being the most likely fate of our shark.”

This is not the first evidence of large sharks eating each other; but we don’t see it very often, and this is the first time we’ve seen such an encounter involving predation of a porbeagle. And the fact that she was pregnant is worrying. In one fell swoop, not one, but several sharks were removed from the porbeagle population, suggesting that predation could be a stressor on the species’ survival that we’ve been overlooking.

Anderson says that the behavior is not likely a newly developed one, but merely one that we have not had the tools to discover before now. Tagging more porbeagles, and other sharks, could help us understand not only why the porbeagles are migrating to the open waters of the North Atlantic, but how often such encounters occur, and what impact they have on the porbeagle population.

“Uncovering the mysteries of the open ocean has always been challenging, and it’s been the development and advancement of satellite tagging technologies in recent decades that has finally allowed us to track and uncover novel behaviors in marine species such as highly mobile sharks,” she told ScienceAlert.

“I think the more of these animals we can tag and track, the more behaviors like this are going to be revealed.”

The research has been published in Frontiers in Marine Science.