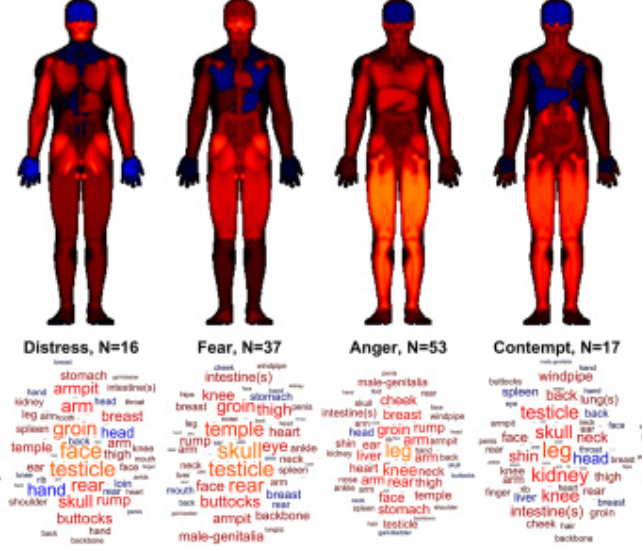

Ask a person raised in Taiwan where they feel their rage most in their body; there’s a good chance they’ll indicate somewhere around their head or chest. Halfway around the world in Finland, you’re bound to find a very similar answer.

No matter where you go today, most of us relate emotions like anger to very similar pieces of anatomy.

Jump in your time machine and set the dial for ancient Mesopotamia; you might find people gesturing to very different parts of their body. According to a recent analysis of thousands of 10th to 7th century BCE Neo-Assyrian texts, anger is an emotion located in the thighs.

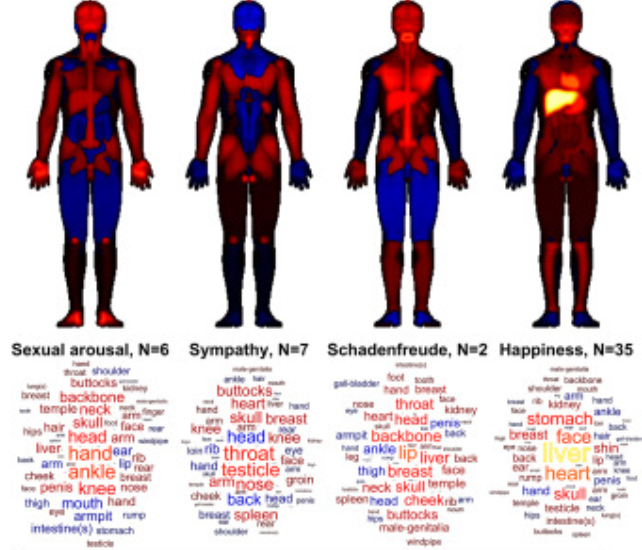

Stranger still, love and happiness are typically anchored in the liver, suffering is often felt in the armpits, and sexual arousal can be a sensation of the ankles, of all places.

Led by cognitive neuroscientist Juha Lahnakoski from the Jülich Research Centre, Germany, a team of researchers sifted through records in the Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, cataloguing terms for emotions and areas of the body.

The result is a heat map of body parts specific to 18 different emotional sensations, from love, anger, and envy to happiness, pride, and even schadenfreude.

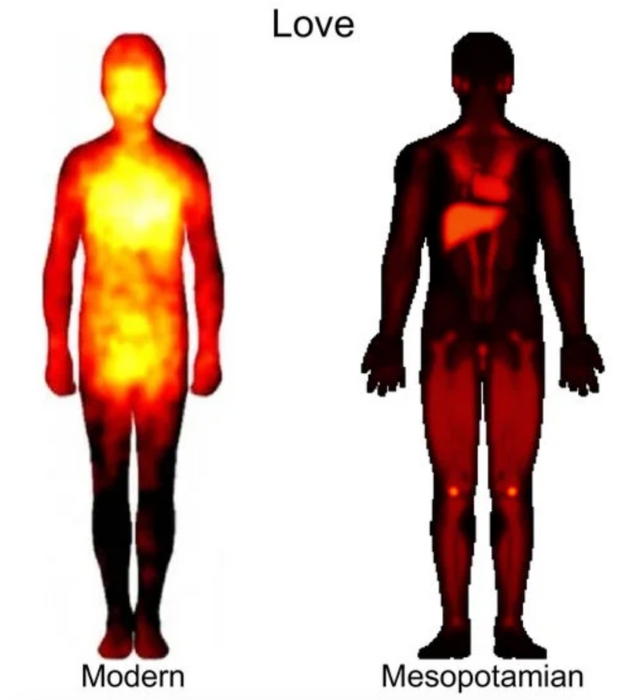

Western cultures share an anatomical atlas of feelings. Allowing for degrees of poetic license, love is usually held in our achy-breaky hearts, lust inflames the loins, steam erupts from our ears when enraged, and fear churns in our guts.

Spare a thought for the poor ol’ liver, shins, and kidneys, which are rarely considered.

These associations are robustly universal, at least in today’s world. Though a degree of variation exists, studies on language and musical sensations across diverse cultures suggest humans everywhere are bonded by the threads of emotional body maps.

On the surface, this similarity may not be all that surprising. The tug-of-war between our parasympathetic nervous system’s ‘rest and digest’ and sympathetic nervous system’s ‘fight or flight’ responses has subtly different effects on our functioning.

Our heart beats faster in anticipation of touching a loved one; our digestive system churns to cope with impending threats; our heads pound with a stress-induced rise in blood pressure.

This implies that humans have generally experienced the same map throughout history.

Testing the assumption, however, isn’t as straightforward as holding up a picture of the human body and asking a paleolithic mammoth hunter where they feel happiness.

So Lahnakoski and his team turned to detailed records of life, politics, and wisdom left by a culture that controlled much of the Middle East nearly 3,000 years ago.

“Even in ancient Mesopotamia, there was a rough understanding of anatomy, for example the importance of the heart, liver, and lungs,” says the study’s senior author, Assyriologist Saana Svärd from the University of Helsinki in Finland.

Putting aside the intriguing contrasts, there was a degree of overlap. Like us, the Assyrians felt their hearts fill with pride and sadness dwelled in their chests. Few emotions were exclusive to any one organ, limb, or zone, either. Love might be felt in the knees, but it also resonated in the liver and heart.

Yet few of us today would express the sympathy we feel deep in our testicles, or the shame we have in our hands, giving us pause to think perhaps the body map of emotions might not be quite as strict as other studies lead us to think.

Interpreting a long-lost culture’s language thousands of years after it was last spoken is fraught with challenges. While the researchers did their best to screen out problematic or confusing terms, the model they used leaves room for interpreting contexts in different ways.

What’s more, an intrinsic bias in the tools used in the study excluded female anatomy, potentially erasing an entire lexicon of terms. The researchers give the example of how the Assyrian word for womb was often used to describe a king’s compassion.

“Also, we have to keep in mind that texts are texts and emotions are lived and experienced,” says Svärd.

Advances in generative language models could further aid our ability to study metaphorical concepts used by different cultures, providing a more nuanced insight into how emotions are related to areas of our body.

As future studies continue to explore the richness of human expression around the world and across the ages, we’ll undoubtedly map the interplay between language and experience that shapes how we communicate, making discoveries that ought to fill our livers with joy.

This research was published in iScience.