Earlier this year, we got news from a landmark study that microplastics – tiny shards of plastic shed from larger chunks – had been found inside more than 50 percent of fatty deposits from clogged arteries. It was the first data of its kind to draw a link between microplastics and their impact on human health.

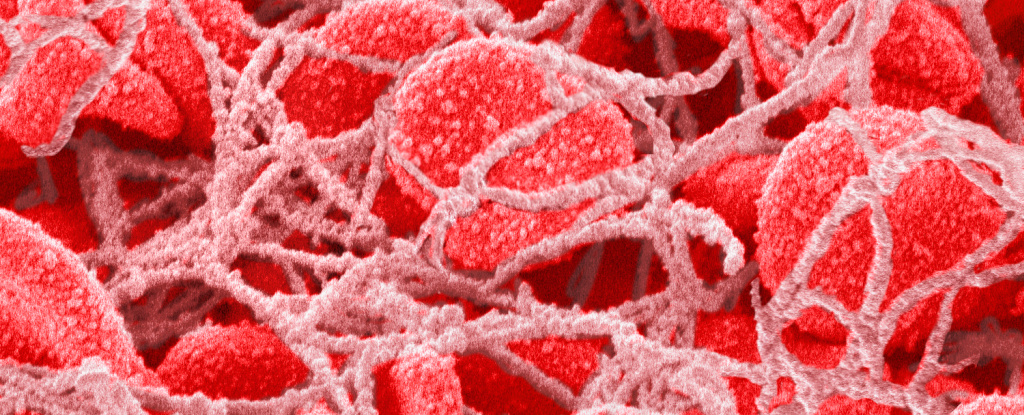

Now, a new study from researchers in China reports finding microplastics in blood clots surgically removed from arteries in the heart and brain, and deep veins in the lower legs.

It’s only a small study, of 30 patients – not nearly as many as the 257 patients followed for 34 months in the arterial plaque study published in March.

But similar to how the Italian-led team found the presence of microplastics in plaques raised people’s subsequent risk of heart attack or stroke, the Chinese team also found a potential association between levels of microplastics in blood clots and disease severity.

The 30 patients involved in the study had surgery to remove blood clots after experiencing a stroke, heart attack, or deep vein thrombosis, a condition where clots form in deep veins, typically of the legs or pelvis.

Aged 65 years old on average, patients had various health histories and lifestyles such as smoking, alcohol use, high blood pressure, or diabetes. They used plastic products daily, and were roughly split between rural and urban areas.

Microplastics of various shapes and sizes were detected using chemical analysis techniques in 24 of the 30 blood clots studied, at varying concentrations.

Testing also identified the same types of plastics as those detected in the Italian-led study of arterial plaques: polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyethylene (PE). This isn’t surprising as PVC (often used in construction) and PE (primarily used in bottles and shopping bags) are two of the most commonly produced plastics.

The new study also detected polyamide 66 in the clots, a common plastic used in fabric and textiles. Of the 15 types identified in the study, PE was the most common plastic, making up 54 percent of the particles analyzed.

The researchers also found that people with higher levels of microplastics in their blood clots also had higher D-dimer levels than patients with no microplastics detected in thrombi.

D-dimer is a protein fragment released when blood clots break down; it’s not normally present in blood plasma. So high D-dimer levels on a blood test can indicate the presence of blood clots, leading the researchers to suspect that microplastics might somehow be massing together in blood to make clotting worse.

But more research is needed to investigate that; this study didn’t measure microplastics in patients’ blood and being an observational study, it can only point to possible links, not causes.

“These findings suggest that microplastics may serve as a potential risk factor associated with vascular health,” Tingting Wang, a clinician-scientist at the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College in China, and colleagues write in their paper.

“Future research with a larger sample size is urgently needed to identify the sources of exposure and validate the observed trends in the study.”

With microplastics previously detected in human lung tissue and blood samples, it’s easy to imagine how these microscopic plastic pieces make their way from the environment into our bodies, and blood clots, if they form – even if scientists can’t trace that pathway step-by-step as it happens.

A 2023 study previously detected the chemical ‘fingerprints’ of microplastics in 16 surgically removed blood clots. Now we have a sense from Wang and team’s work, which used infrared chemical imaging and other methods, of how concentrated those plastic particles can be in blood clots and their possible health effects.

It just shows how fast this field is moving, from detecting microplastics in human tissues, to studying their effects in cells and mice, to now elucidating the health impacts of microplastics in humans.

The results couldn’t come fast enough. Plastic production is only increasing, with fossil fuel companies ramping up their plastics output as their other business prospects crumble.

“Due to the ubiquity of microplastics in the environment and in everyday products, human exposure to MPs is unavoidable,” Wang and colleagues warn.

“As such, microplastic pollutants have sparked growing concern due to their widespread presence and potential health implications.”

The study has been published in eBioMedicine.