Balmy summer nights alive with the sounds of cicadas are so relaxing, until all manner of unruly insects swarm your lights. As much of a nuisance as this may be to us, what’s happening to them is far worse.

Imperial College London zoologist Samuel Fabian and colleagues used advanced videography techniques to discover centuries of rumored affairs between moths and flames were never true.

Rather than aiming for the intense glow, the poor insects are minding their own business, conducting vital nightly tasks like pollination, when a blaring burst of light messes with their sense of up and down.

Flight attitude is a measure of angle compared to Earth’s horizon – kind of critical for keeping on track in the air. Insects evolved mechanisms for attitude correction based on the fact that throughout time, the sky has been significantly brighter than the land.

So when presented with a competing light source, flies, moths, beetles and so on find themselves in an erratic spiral of continued course corrections, giving the illusion of an infatuation with your porch light.

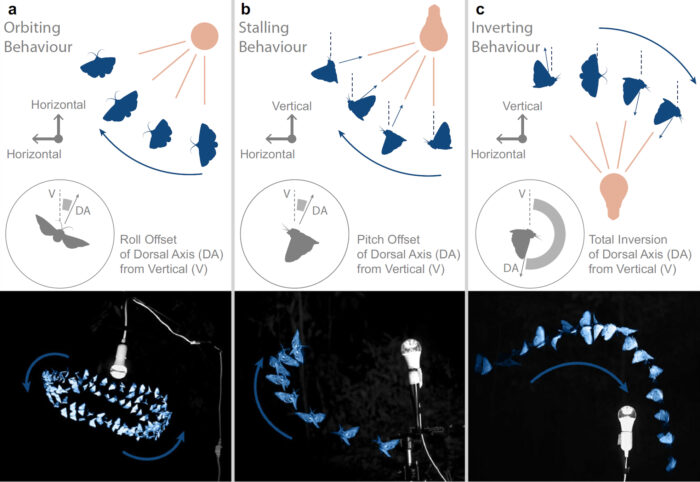

“Contrary to the expectation of attraction, insects do not steer directly toward the light,” the team described. “Instead, insects turn their [back] toward the light, generating flight bouts perpendicular to the source.”

Clashing with other signals for orientation, like gravity, the mixed messages give the unfortunate animals vertigo. It can trick wasps into crashing into things and send dragonflies plummeting towards the ground.

Humans have taken advantage of this light trap for centuries, with the Roman Empire back around 1 CE providing our earliest known written record. Many theories for this phenomenon have since arisen, including that insects must use the Moon for navigation, or are attracted to thermal radiation from globes, but until now our technological limits kept the truth out of our reach.

“3D tracking of small flying objects in low light is technically challenging, and necessary tools did not exist,” Fabian and team write in their paper.

“We leveraged advances in camera hardware and tracking software to consider the sensory requirements for insect flight control, and how artificial light may disrupt them.”

The researchers recorded 477 instances of different types of insects flying near artificial light, to discover repeating patterns of behavior that spun them in disoriented doom spirals or crash courses. However, if the wind threw them off course they were often able to escape.

The researchers then tested different lighting scenarios and found overhead light sources can allow insects to avoid lower light traps.

But their findings only relate to how insects behave around close light sources. To help mitigate the disastrous decline of insects globally, which light pollution contributes to, Fabian and colleagues recommend examining the long distance impacts of our lights at this level of detail as well.

“Taken together, reducing unnecessary, unshielded, upward-facing lights and ground reflections can mitigate the impact on flying insects at night, when skylight cannot compete with artificial sources,” they conclude.

The team’s findings put an ironic spin on the saying “drawn like a moth to a flame,” given these animals sure as heck don’t want to be there and are desperately doing all that they can, yet still often fail, to escape.

This research was published in Nature Communications.