Plastics are affecting our environment and possibly even our health in troubling ways – and the tiniest pieces have now been linked to changes in brain proteins associated with certain types of dementia, including Parkinson’s disease.

A team led by researchers from Duke University in the US looked at the relationship between nanoplastics broken down from polystyrene and the protein alpha-synuclein.

A buildup of aberrant forms of this protein has previously been observed in the brains of people with Parkinson’s.

“Parkinson’s disease has been called the fastest growing neurological disorder in the world,” says neurobiologist and senior author Andrew West from Duke University.

“Numerous lines of data suggest environmental factors might play a prominent role in Parkinson’s disease, but such factors have for the most part not been identified.”

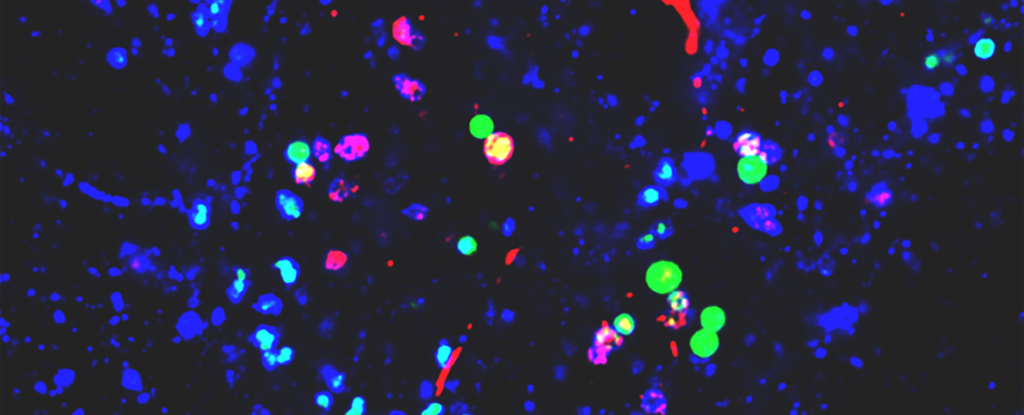

In three different types of experiment – in solutions, in cells cultured in the lab, and in mice genetically engineered to have a predisposition to developing a condition similar to Parkinson’s – the presence of plastics attracted unusually large clumps of alpha-synuclein.

Of particular interest were the tight chemical bonds formed between the nanoparticles of polystyrene and the alpha-synuclein protein, especially in cell lysosomes, where waste disposal is handled.

There’s evidence here that plastic interferes with the natural cleaning process in neurons, which is something that again points to Parkinson’s and diseases like it.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, we should note these are still early findings, and no tests have been done in humans yet. The relationship between nanoplastics and alpha-synuclein isn’t yet clear, nor is the relationship between the congregation of alpha-synuclein and dementia.

It’s worth noting that alpha-synuclein is thought to play an important role in keeping the brain’s neurons healthy – it’s only when it becomes warped or misfolded that problems start. However, determining whether this is a cause or a symptom of diseases like Parkinson’s is proving tricky.

What this study shows is that nanoplastics have an effect on the levels of the protein. The next step is to take a closer look – and that might require new technologies that are better able to monitor levels of plastic and their chemical interactions at the smallest scales.

What we know already is that most of us are already carrying around microscopic particles of plastic in our blood. Figuring out how that is impacting our health is going to be a crucial area of research in the years to come.

“While microplastic and nanoplastic contaminants are being closely evaluated for their potential impact in cancer and autoimmune diseases,” says West, “the striking nature of the interactions we could observe in our models suggest a need for evaluating increasing nanoplastic contaminants on Parkinson’s disease and dementia risk and progression.”

The research has been published in Science Advances.