Every now and again, serendipity gives us a unique window into times long past.

An explosive volcanic eruption that took place in prehistory is one of them. As the ash from a pyroclastic flow during the Cambrian age was dumped on a shallow marine environment, its population of ancient arthropods called trilobites were preserved almost instantly – including any soft tissues that are normally degraded or destroyed during other fossilization processes.

Now, hundreds of millions of years later, those unfortunate animals have given us an unprecedented record of their three-dimensional anatomy, along with any smaller creatures that happened to be clinging to their bodies at the time.

“Cambrian ellipsocephaloid trilobites from Morocco are articulated and undistorted, revealing exquisite details of the appendages and digestive system,” write a team led by sedimentologist Abderrazzak El Albani of the University of Poitiers in France.

“This occurrence of moldic fossils with three-dimensional soft parts highlights volcanic ash deposits in marine settings as an underexplored source for exceptionally preserved organisms.”

In spite of more than 22,000 known trilobite species documented across a span of nearly 300 million years from the beginning of the Cambrian more than half a billion years ago, the number of fossil specimens with intact internal anatomy is extremely limited, and those usually incomplete. That’s because soft tissues don’t tend to survive the temperature and pressure changes that result in the formation of a fossil.

But there is more than one way to make a fossil impression. And, just over half a billion years ago, one of them went off in spectacular style: a volcanic eruption in what is now Morocco that spewed a rain of ash that buried the surrounding region, and a lot of the life in it.

We know such pyroclastic outflows can preserve a snapshot of what they bury. The most famous example is Pompeii, the people of which were buried and cast in millions of tons of ash that rained down on the ancient Roman city, preserving their last moments in horrifying detail.

In the Tatelt Formation in Morocco, a fossil bed with many layers that span ages, there’s a thick layer that comprises volcanic ash and debris. And in those, El Albani and his colleagues found specimens of two species of trilobite.

The features of this ash layer indicate that it was deposited during a single, large, pyroclastic flow event, in which hot ash and gas traveled along the ground away from a volcanic eruption, with minerals indicative of a rapid interaction between hot volcanic material and salty seawater.

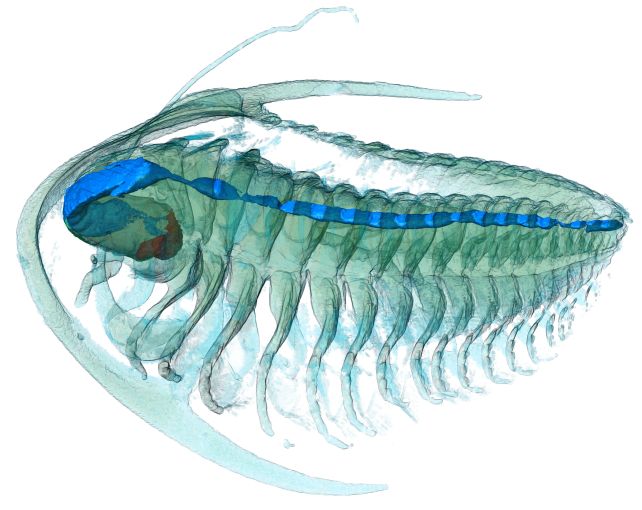

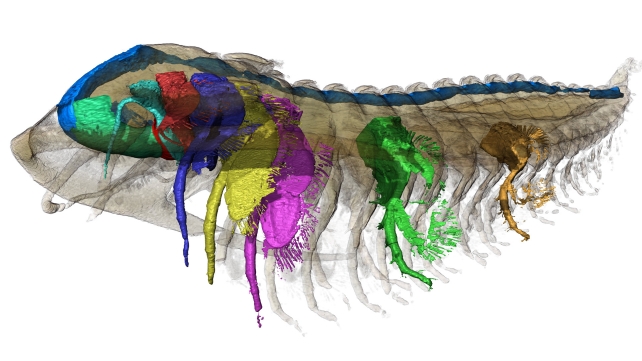

To determine the effect this had on the fossilization process of the trilobite specimens within, the researchers used microtomographic X-ray imaging to reconstruct the interior anatomy of the animals in three dimensions. And what they found was nothing short of spectacular.

They were able to observe the exoskeletons of the trilobites, articulated and undistorted by time. They also probed their antennae, digestive systems, and the complex anatomy around their mouths the trilobites used to feed. Some of the uncovered features had never been identified before.

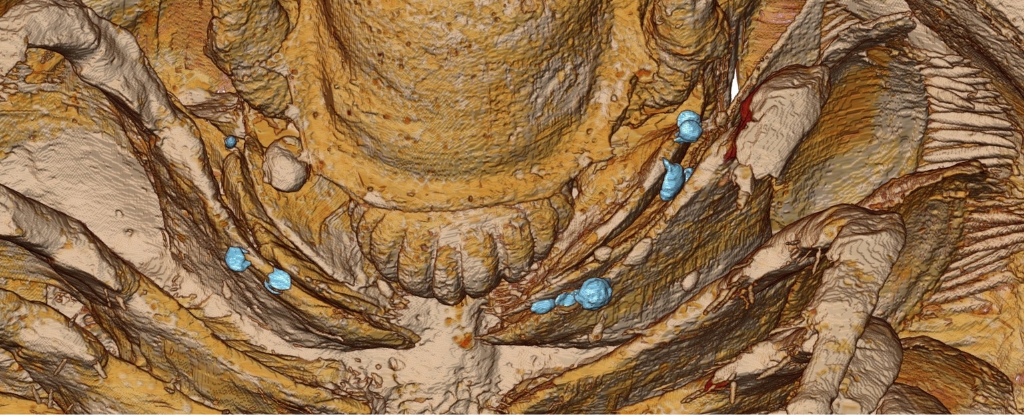

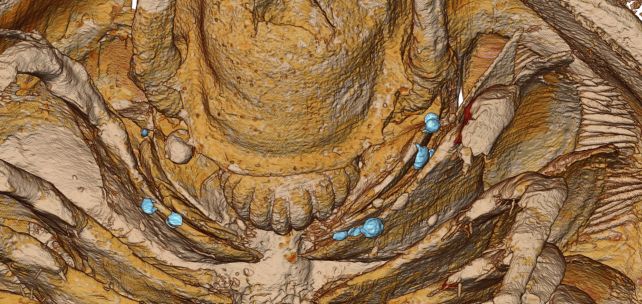

The pyroclastic flow even preserved tiny brachiopods – tiny clam-like creatures that adhered to the shell of the trilobites in an epibiotic relationship. These brachiopods are in a relaxed life position, suggesting that the two species died together, either buried alive, or not long after death.

They were even able to resolve a long-standing debate about trilobite mouths. Their scans revealed, for the first time, a mouth part called a hypostome constructed of soft tissue.

Previous researchers had theorized, due to the absence of a clear hypostome in other trilobite fossils, that perhaps it was part of a different mouth part called the labrum. The new research shows that, in both trilobite species, the hypostome and labrum are two separate structures.

We now know just that little bit more about one of the most abundant animal groups ever to exist on our planet, but the research also highlights an untapped paleontological resource.

“Although the soft-bodied anatomy of trilobites has been known for over 100 years, the Tatelt specimens reveal critical details at a level not previously observed, despite the long stratigraphic range and abundance of this iconic group of Paleozoic fossils,” the researchers write.

“The extraordinary preservation of fine anatomical detail in the ash deposit of a pyroclastic event is unexpected but points to the great potential of ash deposits in marine settings to yield further discoveries.”

The research has been published in Science.