The fossilized remains of a new horned dinosaur have just been discovered in the mountains of Montana. And it’s a giant.

Lokiceratops rangiformis is one of the largest ceratopsian dinosaurs to have ever roamed our planet, belonging to a family of horned beasts that includes Triceratops and Styracosaurus.

What’s more, the two long, curving horns that adorned the crest of its skull are the most astonishing ever documented. It’s for these horns that the dinosaur gets its name, from the spectacular helmet worn by the Marvel character Loki.

Lokiceratops lived 78 million years ago, alongside several other frilled dinos of the Centrosaurine subfamily in what was once the Cretaceous island continent of Laramidia, but it was larger and heavier than all of them.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

Although the bones are all from just a single individual, by a huge stroke of luck they make up most of the dinosaur’s skull.

From this, we know that Lokiceratops had horns unlike any other, crowned by the two large, caribou-like asymmetric horns on the top of the frill – the large, shield-like bony plate found in ceratopsians. It also lacked the nose horn typical in other beasts of its ilk.

“This new dinosaur pushes the envelope on bizarre ceratopsian headgear, sporting the largest frill horns ever seen in a ceratopsian,” says paleontologist Joseph Sertich of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. The paleontologists believe the dinosaurs used their horns much like birds use their different feathers, for mate selection or species recognition.

“These skull ornaments are one of the keys to unlocking horned dinosaur diversity and demonstrate that evolutionary selection for showy displays contributed to the dizzying richness of Cretaceous ecosystems.”

The fossilized bones were found in the Judith River Formation in Montana, a fossil deposit from which the bones of four other dinosaurs have been retrieved.

But, when Sertich and his colleague, paleontologist Mark Loewen of the University of Utah, started reconstructing the skull from bones excavated in 2019, they realized they were looking at something nobody had ever seen before.

And it was, dare we say, a chonker.

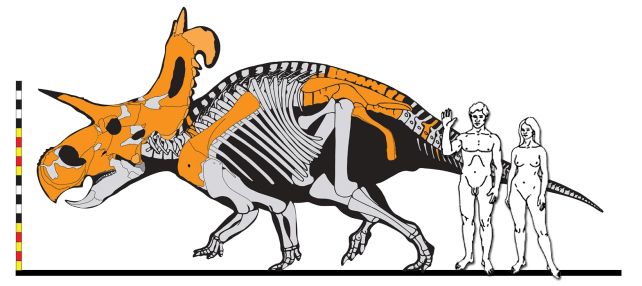

Lokiceratops is estimated to have measured some 6.7 meters (22 feet) in length, with a skull more than 2 meters long from nose to horn-tips. And it would have tipped the scales at around 5 metric tons (11,000 pounds). That puts it on a par with the largest elephants found on Earth today.

It’s still not quite as big as Triceratops, which came along around 10 million years later in Earth’s history, but you’d still want to get out of its way if it was charging at you, head lowered.

Another interesting thing about Lokiceratops is the other dinosaurs in the formation in which its remains were found.

Three of the other species are also Centrosaurines, closely related to each other and Lokiceratops, and the fourth was another horned dinosaur. The other Centrosaurines are also not known outside Laramidia.

“Previously, paleontologists thought a maximum of two species of horned dinosaurs could coexist at the same place and time,” Loewen explains. “Incredibly, we have identified five living together at the same time.”

The isolation of ceratopsian dinosaurs on Laramidia is likely what led to the large sizes and diversification of the animals found there, including the distinctive arrangements of horned protuberances on their giant heads. This rapid speciation can be found in isolated animal communities, most notably the finches in Galapagos.

This suggests that we may be vastly underestimating the diversity of dinosaurs, the researchers say.

“Rapid evolution may have led to the 100- to 200-thousand-year turnover of individual species of these horned dinosaurs,” Loewen says, adding, “Lokiceratops helps us understand that we only are scratching the surface when it comes to the diversity and relationships within the family tree of horned dinosaurs.”

The research has been published in PeerJ.