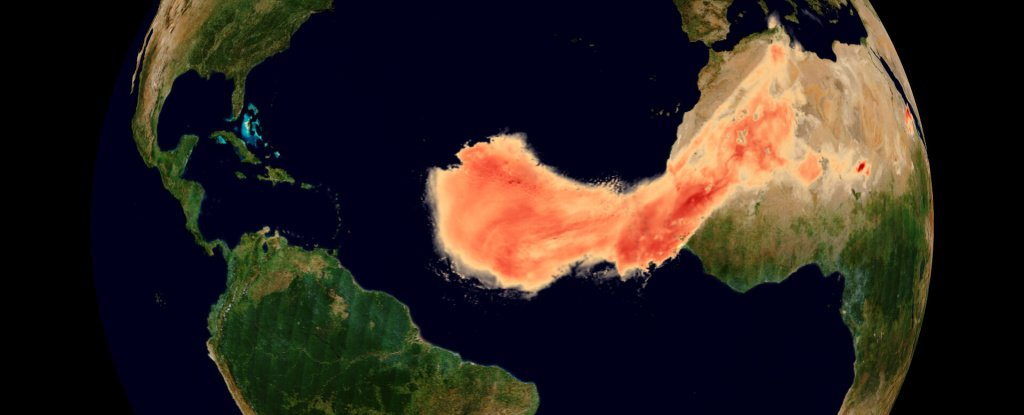

Dust swept from the Sahara desert provides life at the bottom of the marine food chain with a critical nutrient. Without the iron carried far and wide in this mineral cloud, oceanic phytoplankton would struggle to bloom.

According to a new study led by the University of California, Riverside, the more time the dust spends aloft in the atmosphere, and the further it travels, the more its iron is converted into a form that is easily accessed by the biosphere below.

“The transported iron seems to be stimulating biological processes much in the same way that iron fertilization can impact life in the oceans and on continents,” says biogeochemist Timothy Lyons. “This study is a proof of concept confirming that iron-bound dust can have a major impact on life at vast distances from its source.”

Barren desert dust from North Africa is Earth’s largest source of airborne particles. Wind shifts around 800 million metric tons of it westward every year, all the way over to the Americas, carrying isotopes of iron scoured from the desert’s exposed surface.

The metal has a vital role to play in biochemical pathways that secure carbon in the atmosphere into organic molecules. As essential as iron is to life, however, its availability is limited, meaning this nutrient’s distribution dictates much of where life can be found on Earth.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

Not all forms of iron are easy for living organisms to make use of. Conditions in the atmosphere might make a big difference to the iron menu that eventually settles onto the ocean’s surface.

“Dust that reaches regions like the Amazonian basin and the Bahamas may contain iron that is particularly soluble and available to life, thanks to the great distance from North Africa, and thus a longer exposure to atmospheric chemical processes,” explains Lyons.

Biogeochemist Bridget Kenlee and colleagues discovered this by analyzing drill cores from the bottom of the ocean. They found that while total dust decreased with transport distance, the amount that had biologically usable iron that dissolves in water actually increased with that distance.

“This relationship suggests that chemical processes in the atmosphere convert less bioreactive iron to more accessible forms,” says Owens.

With its heavy mass of bioactive iron, the dust fuels a vast food chain thousands of miles from its origins, fertilizing the phytoplankton in the ocean as well as the plants all the way over to the Amazon. These two systems produce much of the oxygen we all breathe.

Previous studies have suggested these patterns of bioactive iron match with areas of increased biological activity. This includes more microbe activity on the surface to the Caribbean coral reefs and the fertilization of the Amazon region.

A seven-year study found an average of 28 million metric tons of North African dust provides the Amazon River basin with about 22,000 tons of fertilizing phosphorus as well.

Other research similarly found dust from Asia has fertilized Hawaii’s rainforests for millennia.

The Saharan dust clouds can cause problems with their presence too, like triggering allergies in humans. They even have the power to smother hurricanes.

Despite the barren origins of this lofted soil, and any problems it might cause, grains from the Saharan desert carry vital fuel for life on Earth, providing another example of how incredibly interconnected the physical processes of our planet are with the life that calls it home.

This research was published in Frontiers in Marine Science.