The human body undergoes profound physiological changes during pregnancy, and the brain is no exception.

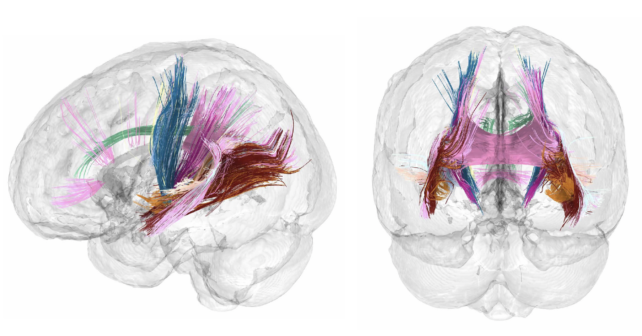

Neuroscientists in the US have now provided the first detailed map of the human brain across gestation.

The breakthrough is based on the neurological changes of one first-time mother, who had snapshots of her brain taken before, during, and after pregnancy.

As the pregnancy advanced, researchers noticed a widespread shrinking of gray matter, which is the brain tissue that includes the bodies of neurons.

While shrinking parts of the brain might sound scary, these changes are probably for the best. They may reflect a re-wiring of the brain’s finite tissue for motherhood.

Researchers found the links between neurons, which make up white matter, had increased their connectivity in the final two trimesters of pregnancy.

When neuronal circuits are fine-tuned for whatever reason, gray matter tends to be pruned back while white matter connections increase, allowing information to travel around the brain more efficiently.

Neuroscientist Emily Jacobs from the University of California Santa Barbara compares the process to Michelangelo chipping away at a carving of David. The artist starts with a big block of marble, she explains, but through careful honing it turns into a refined piece of art.

“We’ve never witnessed the brain in the midst of this metamorphosis,” Jacobs said in a press briefing.

“We were able to observe sweeping changes in gray matter volume, cortical thickness, white matter microstructure, and ventricle volume as it all unfolded week by week.”

Not so long ago, neuroscientists used to think the human brain was ‘hard-wired’ with fixed circuits of neurons. Now we know better. The brain is actually soft-wired, meaning it is plastic and malleable, undergoing significant changes as we learn and age.

The idea of plasticity took the field of neuroscience by storm, and now, another revolution is on the horizon.

To date, barely 2 percent of neuroimaging studies mention sex hormones as influencing factors, even though the few papers that are published suggest there is a statistically significant association between sex steroids and changes in the brain.

In 2024, for instance, researchers documented in detail the structural changes that take place in the brain as hormones change during menstruation.

But there are only a handful of studies that have investigated what happens to the brain during pregnancy, according to neuroscientist Elizabeth Chrastil from the University of California, Irvine.

In 2017, researchers showed that pregnancy coincided with significant reductions in gray matter, and in 2022, a follow-up study among 28 volunteers found that pregnancy hormones changed the way the brain’s networks are wired.

“There is so much about the neurobiology of pregnancy that we don’t understand yet, and it’s not because women are too complicated; it’s not because pregnancy is some Gordian knot,” says Jacobs.

“It’s a byproduct of the fact that the biomedical sciences have historically ignored women’s health. It’s 2024, and this is the first glimpse we have at this fascinating neurobiological transition.”

The new MRI study tracked a 38-year-old woman, who had not had kids before, and who underwent in-vitro fertilization (IVF) to achieve pregnancy.

The female participant underwent 26 MRI scans in total, including four scans three weeks before conception, multiple scans in the first, second, and third trimester, and seven scans in the two years postpartum. Researchers also took blood samples from the participant throughout this timeline.

During pregnancy, over 80 percent of the brain regions that neuroscientists examined showed reductions in gray matter of about 4 percent, on average, although everything returned to normal at the end of the pregnancy. That’s about the same magnitude of change observed during puberty, the authors say.

How these brain changes relate to behavioral changes is unknown. All we have at the moment are animal studies to point to, and the majority of these are conducted on male brains.

In pregnant rodents, some studies have found a surge in estrogen and progesterone reprograms brain circuits like the hypothalamus, which enhances a mother’s sensitivity to the smells and sounds of her newborn pups.

Perhaps something similar is happening in humans, although our physiology is more complex, and the findings among rodents may not relate.

“This paper really opens up more questions than it answers because really we’re just starting to scratch the surface of understanding what does this mean for postpartum depression or… how does pregnancy possibly help alleviate some things like migraines?” says Chrastil.

“This is really just sort of opening up the box.”

The study was published in Nature Neuroscience.