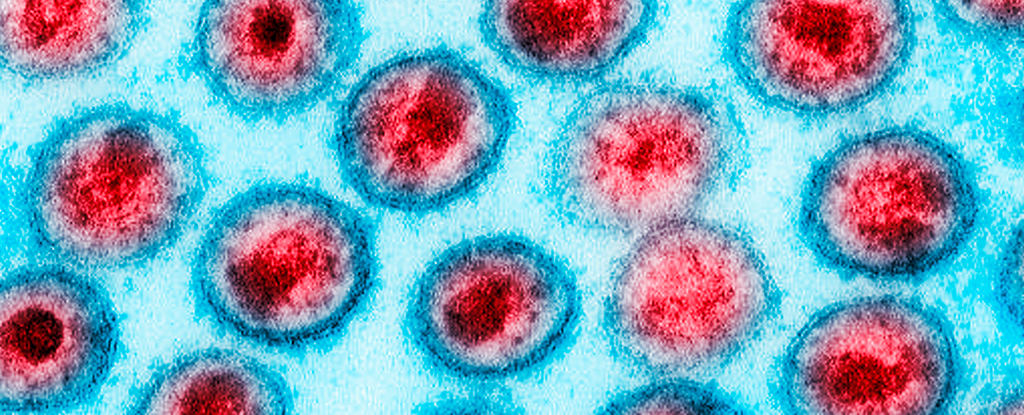

A new randomized controlled trial adds weight to claims that circumcision may reduce the risk of infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among men who have sex with men.

While observational studies have found removal of the foreskin can impede the transfer of STIs like HIV among this demographic, the possibility of sampling biases have left conclusions open to debate.

The recent study led by researchers from Sun Yat-sen University in China used blood tests to compare two randomly-assigned groups of men who voluntarily underwent circumcision over a twelve month period.

HIV remains a major public health threat in some parts of the world, claiming hundreds of thousands of lives per year. While the global death rate has dropped since the early 2000s, some countries in Africa still bear a disproportionate burden.

There is still no cure for an HIV infection, although treatment options have improved in recent years, as have efforts focused on education and prevention.

And while it may not rival more reliable preventive measures such as condom use, research suggests circumcision can reduce the risk of HIV transmission in at least some cases.

Previous research has shown male circumcision is associated with lower rates of several sexually transmitted infections, including syphilis and chancroid. Studies also suggest heterosexual men who are circumcised face a lower risk of contracting HIV.

In the new study, researchers from China and the US enrolled 247 uncircumcised men between the ages of 18 and 49 from eight cities in China, all of whom were HIV-seronegative. The study participants all self-reported having primarily insertive anal intercourse, and having had two or more male sex partners in the past six months.

All men in the study received HIV counseling and testing, and then were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group.

The 124 men in the intervention group received immediate circumcision, the authors report, while the remaining 123 in the control group had their circumcision delayed by a year.

During the study period, the men in the intervention group experienced zero seroconversions – the time window when the body begins producing detectable levels of antibodies in response to an HIV infection.

In other words, none of the men who received circumcisions at the outset of the study later became infected with HIV.

The control group, on the other hand, experienced five seroconversions, indicating a handful of men became infected with HIV during the course of the study. The study found no statistically significant differences in infection rates of three other sexually transmitted diseases tested for.

There are some noteworthy caveats with the new study. As the authors acknowledge, the sample size was smaller than ideal, and the overall rate of HIV infection was lower than expected.

Though circumcision is a common and ancient tradition among many cultures, it’s ongoing practice is controversial, especially when carried out on minors. Advocacy of non-consensual circumcision as a public health intervention can be a sensitive subject.

Campaigns promoting circumcision in Africa have faced criticism, for example, largely centering on the dynamic of Western governments and NGOs pushing the practice in African communities, often based on what critics describe as faulty or overstated evidence.

As one 2020 study put it, these campaigns “were started in haste, without adequate contextual research, and the manner in which they have been carried out implies troubling assumptions about culture, health, and sexuality in Africa, as well as a failure to properly consider the economic determinants of HIV prevalence.”

The framing of circumcision as a solution to African HIV epidemics “has more to do with cultural imperialism than with sound health policy,” the authors of the 2020 study argued.

The new study does suggest voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) could offer some protection against HIV infection for men who have sex with men, although the researchers are careful not to overstate the implications.

“While VMMC may exhibit high protective efficacy, the authors caution that it is important to offer comprehensive protection against HIV with additional preventive measures,” they write.

“Recommendations include condom use, education to reduce the number of partners, regular HIV testing, and pre-exposure or post-exposure prophylaxis, as appropriate.”

The study was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.