Your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease depends largely on your genes and your age, but that doesn’t mean it’s out of your hands. As a new study suggests, you might have more influence on the matter than you think.

The study’s authors introduce another key indicator for Alzheimer’s risk that may warrant more attention: your ‘bioenergetic age’, which isn’t necessarily the same as your chronological age.

Bioenergetics is a field of biochemistry focused on the transformation of energy in living things. Your bioenergetic age represents how efficiently (i.e., how youthfully) your cells generate energy.

This metric may not only improve the accuracy of Alzheimer’s risk assessments, the study finds, but could also help empower patients to mitigate their own risk. While bioenergetic age is dictated partly by genes and the passage of time, it’s malleable in ways chronological age is not.

“That’s quite big because it means some people can lower their risk without the uncertain side effects of current treatments,” says senior author Jan Krumsiek, physiologist at Weill Cornell Medicine.

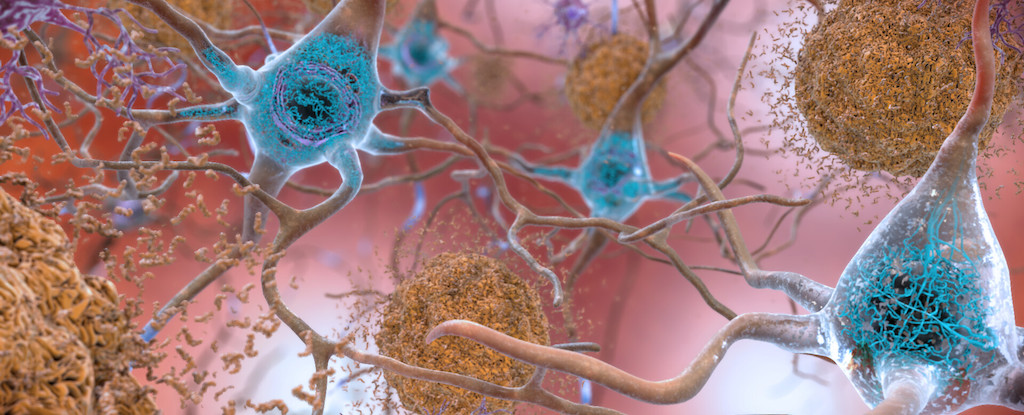

It may also help explain why Alzheimer’s can progress so differently in people with similar early signs of the disease, like cells that begin using and producing energy less efficiently.

While many people with this warning sign soon develop Alzheimer’s symptoms, others mysteriously remain symptom-free for years.

A special ‘bioenergetic capacity’ seems to protect these patients, helping them maintain normal energy levels despite pathological anomalies in their energy pathways, the researchers write.

“In these cases, people can be unusually healthy when we look at their cognition,” Krumsiek says. “They make it to old age without the kind of declines that usually creep in.”

The next step was to find a test that can identify which patients already have this higher bioenergetic capacity, and a way to cultivate it in those where it’s lower.

The researchers focused on a class of fatty acid metabolites known as acylcarnitines found in the blood, which previous studies have established as markers of cognitive decline and energy metabolism.

Using data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), they investigated whether acylcarnitine levels in blood can clarify Alzheimer’s risk.

Higher acylcarnitine levels correlate with a higher bioenergetic age, which is associated with more severe Alzheimer’s pathology and cognitive decline, the study found.

The researchers used a common 11-question test to assess cognitive decline, finding patients with low acylcarnitine levels declined less quickly, losing about half a point less per year than patients with high acylcarnitine levels.

That rate is comparable to that of patients taking lecanemab, they add, suggesting that having a lower bioenergetic age could be protective against Alzheimer’s.

“It was fascinating,” Krumsiek says. “Dividing research participants into groups based on their specific acylcarnitine levels highlighted people with more severe Alzheimer’s disease and others with fewer symptoms.”

This suggests acylcarnitines can help us read our bioenergetic clocks, revealing how old we seem based on our metabolism rather than the date of our birth. Luckily, a cheap test for acylcarnitine levels in blood already exists.

“It’s fortunate that these blood tests – originally developed to identify metabolic and mitochondrial disorders in newborns – can also help assess a person’s bioenergetic age,” Krumsiek says.

“If we can repurpose this technology for older adults, that could provide a way to start personalized treatment earlier.”

That treatment could include behavioral shifts to boost exercise and nutrition, reducing patients’ bioenergetic age and thus their Alzheimer’s risk.

Interventions like these might yield the most benefit for patients with a high bioenergetic age but also a favorable genetic profile, the researchers suggest, noting that about 30 percent of participants from the ADNI study fit that description.

Future research should also explore which interventions are most effective in reducing a person’s bioenergetic age, the researchers say.

The study was published in Nature Communications.