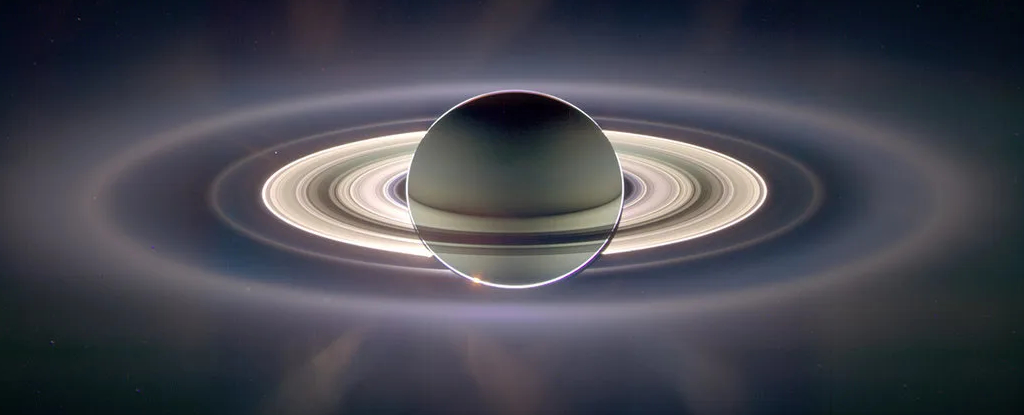

It’s hard to imagine Saturn without its glorious, extensive, complicated rings. Yet, when the Cassini probe arrived to study the planet in 2004, it made a curious discovery: the ice chunks and particles that make up the rings were strangely clean, devoid of the dust astronomers expected to find as a result of constant micrometeoroid bombardment over billions of years.

Scientists thought that meant the rings had not always been there; that they were, in fact, no more than 100 to 400 million years old. Dinosaurs could have been stomping across Earth with a naked, ringless Saturn in the sky above them.

Well, you can ease that disconcerting mental picture from your brain. A new study by researchers from the Institute of Science Tokyo and the French National Centre for Scientific Research has found that Saturn’s rings may be ancient after all – with a neat explanation for how the ice within them may have remained clean as a whistle.

“Data from the Cassini spacecraft suggested the rings might be young because they appear so clean, and many people simply accepted that conclusion. However, our theoretical work now shows that a clean appearance does not necessarily mean the rings are young,” planetary scientist Ryuki Hyodo of the Institute of Science Tokyo told ScienceAlert.

“So, I think this is an important insight for guiding future planetary exploration missions; you better not be fooled by its first glance.”

Although the other giant planets in the Solar System have rings, too, they are nothing like Saturn’s. Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune are all banded by dainty, ethereal rings that can hardly be seen unless you use the right observing wavelengths.

Saturn, by contrast, is practically defined by its extensive rings. It seems likely that, outside the Solar System, rings could be common, given the large number of gas giant exoplanets identified – but we don’t know much about rings like Saturn’s. If they are relatively short-lived, lasting just a few hundred million years before collapsing, our experience of them may have just been a case of being in the right place at the right time.

But if they are longer lived, that doesn’t just have implications for the Solar System; majestic planetary rings may reasonably be something we can factor into puzzling observations of other stars.

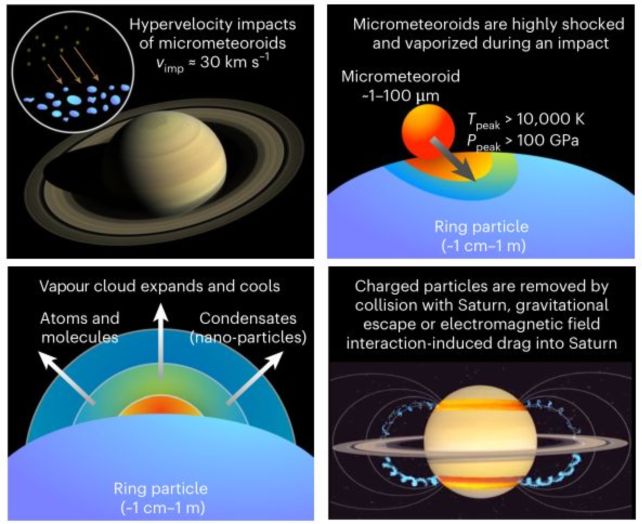

The assumption of the youth of Saturn’s rings was based on the absence of dust from the constant bombardment of high-speed meteoroids slamming into the ice that makes up the rings. Hyodo and his colleagues wanted to know if there could be another explanation for the rings’ youthful appearance, so they conducted theoretical modeling to see what happens when you smack a dust particle at high speed into ice in the cold vacuum of space.

Tiny micrometeoroids, less than 100 microns in size, are zipping around Saturn, accelerated by Saturn’s powerful gravitational pull. Meanwhile, the ice chunks that make up the rings can be quite a bit bigger, from centimeters to meters in size.

When a particle traveling at more than 25 kilometers (about 15 miles) per second smacks into an ice chunk, rather than polluting the ice, the heat of impact causes both the micrometeoroid and a tiny area on the surface of the ice to vaporize; some of which condenses into nanoparticles, the rest of which remains atoms and molecules.

From there, “the nano-particles and atoms and molecules are charged in the plasma environment around Saturn; once charged, Saturn’s magnetic field affects the orbits of charged nano-particles and ions,” Hyodo explained.

“In the end, micrometeoroid material (darkening material of rings), now in the form of nano-particles and ions, either slam into the planet or escape into Saturn’s atmosphere or out into space. In conclusion, the rings hardly get darkened by micrometeoroid impact.”

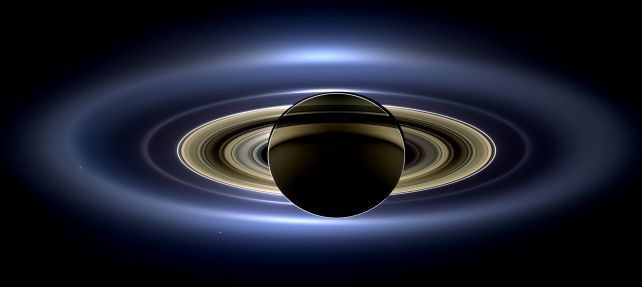

If this is the case, the rings of Saturn could be billions of years old. In addition, the phenomenon could mean that Saturn’s rings will be around for longer in the future than we thought. Cassini detected huge amounts of water falling from Saturn’s rings down onto the planet – enough to fill an Olympic pool every half-hour.

The observed falling material was interpreted as the rate at which the rings are decaying; with as little as 100 million years before they are gone beyond recognition. But, Hyodo and his colleagues found, ring rain could be the vaporized water from micrometeoroid bombardment.

If Saturn’s rings are older, they are also easier to explain. The Solar System was much more chaotic billions of years ago, increasing the odds of an event such as a collision between asteroids or baby planets that created clouds of debris that spooled around Saturn and became its rings.

At the moment it’s just a hypothesis – but it would certainly tidy up several ongoing questions about Saturn and its rings. Hyodo and his colleagues are working to explore their findings further.

“Following our study, my colleague is now conducting laboratory experiments to simulate micrometeoroid impacts on icy particles. These experiments can help further validate our results,” he told ScienceAlert.

“In addition, I’m leading scientific teams on several Japanese planetary exploration missions, including a potential future mission dedicated to studying Saturn’s rings more closely. Such a mission would allow us to approach the rings at a much closer distance than Cassini did, enabling us to observe impact events directly or collect indirect evidence that could shed more light on the rings’ age.”

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.