The Moon might be a bit of a dark horse when it comes to water.

According to a new analysis of mineralogy maps, water and hydroxyl – another molecule made up of hydrogen and oxygen – can be found in multiple locations across all lunar latitudes and terrains, even where the Sun shines down most powerfully.

It’s a discovery that has multiple implications. It can help us understand the Moon’s geological history and ongoing processes, and inform future crewed missions to Earth’s satellite.

“Future astronauts may be able to find water even near the equator by exploiting these water-rich areas. Previously, it was thought that only the polar region, and in particular, the deeply shadowed craters at the poles were where water could be found in abundance,” says planetary scientist Roger Clark of the Planetary Science Institute.

“Knowing where water is located not only helps to understand lunar geologic history, but also where astronauts may find water in the future.”

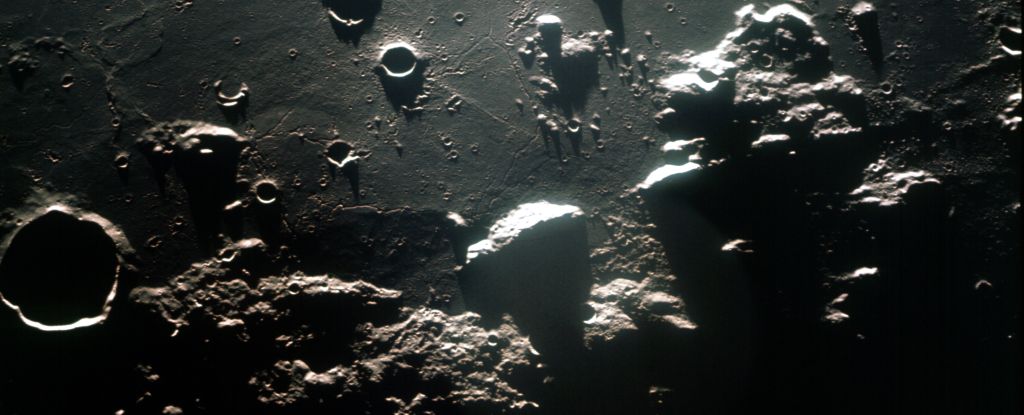

The Moon seems pretty dry and devoid of moisture, and in one sense it is. There is no liquid water pooling on the surface – no lakes, puddles, or rivers. But studies are increasingly showing that the Moon has plenty of water tucked away.

Previous studies into where all the water might be hiding suggested that a huge amount could be deep in lunar craters, particularly at high latitudes. These deep pockets are never touched by the direct light and heat of the Sun, which means they may be harboring deposits of ice several meters thick.

But other recent work has found that other parts of the Moon could have water, too. And now, the work of Clark and his colleagues supports this finding. Water and hydroxyl – consisting of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom – appear to be pretty abundant on the Moon, bound up in the minerals that form the rocks and dirt on the surface of the Moon.

The researchers used data from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) instrument on the Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft, which orbited the Moon in 2008 and 2009, collecting spectroscopic images of the Moon. This data recorded the infrared light reflected by the Moon, looking for colors on the spectrum consistent with water and hydroxyl.

The researchers found that water and hydroxyl can be found across all latitudes on the Moon, although the molecules appear to be less abundant in lunar mares. But the water-rich rocks that are excavated during impacts can be found wherever such impacts take place.

Water doesn’t stay forever. The researchers found that water in the lunar surface is is exposed in cratering events and then gradually destroyed by radiation from solar wind over a timeframe of millions of years. But this process leaves behind hydroxyl. Hydroxyl is also produced by the solar wind, which deposits solar hydrogen on the surface of the Moon, which can bind with oxygen there to produce the molecule.

“Putting all the evidence together, we see a lunar surface with complex geology with significant water in the sub-surface and a surface layer of hydroxyl,” Clark says. “Both cratering and volcanic activity can bring water-rich materials to the surface, and both are observed in the lunar data.”

The researchers also found that the water signature of pyroxene – a type of igneous rock – changes depending on the angle of the sunlight hitting it. This tidies up a lunar mystery: scientists had observed this changing signature and not known what it meant. It seemed to suggest that water was moving around on the Moon. It still could be, but not as much as the pyroxene signature had seemed to indicate.

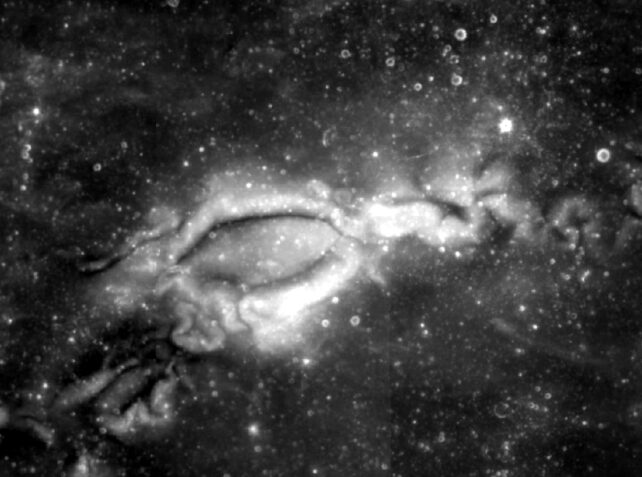

Finally, the team’s maps give us some more information about another weird Moon mystery – the lunar swirls. These are strange, swirling patterns on the surface of the Moon, and scientists don’t know what makes them, although magnetism could play a role. Clark and his team found that the swirls are very water-poor.

We don’t know what that means for their formation mechanism, but this signature also occurs on parts of the lunar surface that don’t have a swirl pattern. These parts, the researchers think, could be ancient swirls that have eroded, leaving only a telltale water signature to tell us they were once there. And that could help us work out what the swirls actually are.

Meanwhile, the discovery suggests a possible water source for lunar explorers. By processing the hydroxyl-rich minerals, future astronauts could, indeed, find a way to squeeze water out of a stone.

The research has been published in The Planetary Science Journal.