A little-known form of dementia, easily mistaken for Alzheimer’s disease, now has a brand new name and specific diagnostic criteria.

Researchers are calling it limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), and they hope that their work makes it easier for medical professionals to care for and counsel patients with various forms of memory loss.

LANS presents with a different set of brain changes to Alzheimer’s, and it tends to progress slower and with milder symptoms, mostly impacting those over the age of 80.

Similar to Alzheimer’s, a definitive diagnosis is only available upon autopsy.

To help those living with memory loss, neurologist Nick Corriveau-Lecavalier and his colleagues at the Mayo Clinic, along with other institutions in the US and Spain, have provided an official framework by which to distinguish LANS from Alzheimer’s.

“In our clinical work, we see patients whose memory symptoms appear to mimic Alzheimer’s disease, but when you look at their brain imaging or biomarkers, it’s clear they don’t have Alzheimer’s,” says senior author and Mayo neurologist David Jones.

“Until now, there has not been a specific medical diagnosis to point to, but now we can offer them some answers.”

The more precise diagnosis considers factors such as age, the severity of memory loss, brain scans, and biomarkers.

In a trial, the new diagnostic criteria successfully categorized dozens of patients who had died with Alzheimer’s disease or LANS, based only on health data from when they were alive. The success rate was not perfect, but the accuracy was over 70 percent.

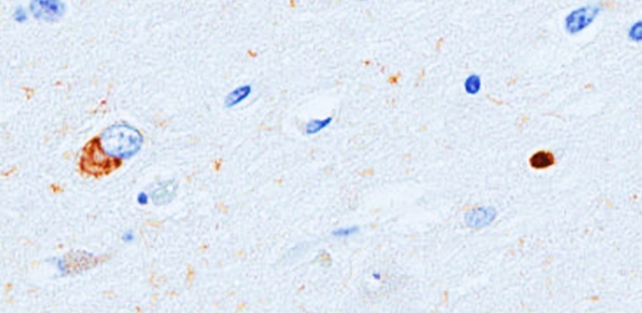

As it turns out, the set of clinical criteria for LANS has a high likelihood of being associated with brain changes caused by limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy – aka LATE.

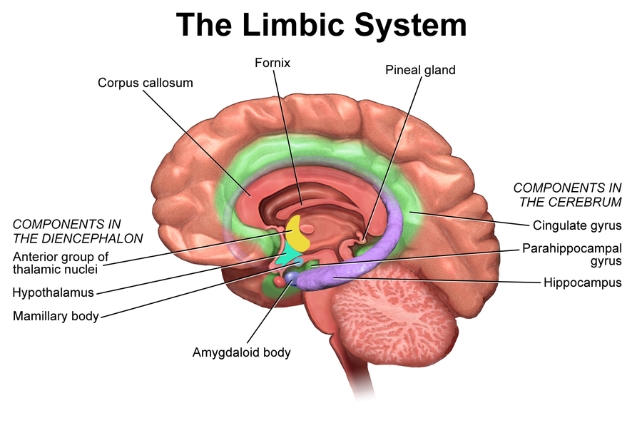

In the study, most patients with LATE brain changes scored the highest for a LANS diagnosis, but the authors note that while the two terms are “highly associated”, LANS can technically cover any form of dementia that leads to degeneration of the limbic system.

The brain changes in LATE are highly common in elderly folk, occurring in about 40 percent of autopsied brains beyond age 85. They are marked by a buildup of protein, called TP-43, in the limbic system, which is a brain network involved in regulating memory, emotions, and behavior.

These brain changes are distinctly different to the tau protein tangles that occur in Alzheimer’s disease, and which tend to accumulate in parts of the brain involved in spatial awareness and spatial reasoning.

In 2019, an international consensus report recommended that LATE brain changes should be part of the dementia classification system.

Alzheimer’s and LANS have significant overlaps in symptoms, which means they are often conflated. Sometimes LANS can even arise alongside Alzheimer’s, complicating matters even more.

But the two diseases are distinct.

Sifting through available studies on both forms of dementia, researchers at the Mayo Clinic have identified some key clinical differences in how LANS and Alzheimer’s present in patients.

Patients with LANS tend to first suffer from episodic memory loss, which reduces their ability to recall contextual details or names of objects and people, and reduces verbal fluency. But their visuospatial processing is relatively preserved compared to those with Alzheimer’s.

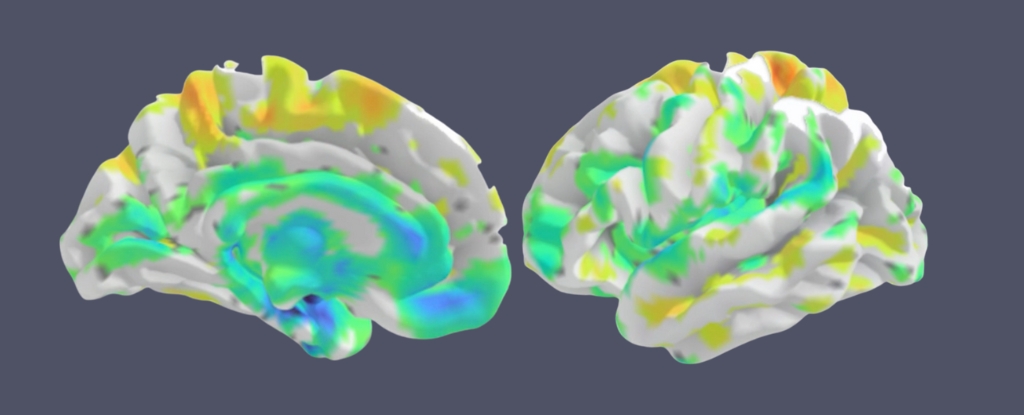

Additionally, MRI studies suggest that a loss of volume in the hippocampus is associated with LANS more so than Alzheimer’s, where losses in volume tend to be focused in the neocortex.

LANS also appears to come on slower and with more mild effects than the faster rate of decline seen in Alzheimer’s disease, and the even steeper rate of decline observed in those who have both LANS and Alzheimer’s.

“One example that can be a potential source of clinical conundrums is the limbic variant Alzheimer’s disease, where tau predominantly localizes to the limbic system and therefore qualifies for LANS,” the authors explain.

“The advanced LANS criteria in combination with visual assessment of tau-PET can help in determining which pathology has the highest likelihood of driving clinical symptoms.”

Disentangling the various forms and mechanisms of dementia is clearly tricky work, but the team at Mayo plans to continue refining their LANS classification.

The study was published in Brain Communications.