Researchers have published a comprehensive sonic survey of the blue whale in the Antarctic: it covers almost 3,900 hours of sound, gathered across 15 years, and focuses on three distinct types of call made by these fascinating creatures.

While the blue whale is the largest animal on the planet – growing up to 30 meters (98 feet) in length – it’s also an endangered species that lives in a remote habitat, and monitoring these whales across the vastness of the oceans isn’t easy.

That’s where passive acoustic devices called sonobuoys come in. These are special buoys that can detect sonar, which means when they are plopped in the ocean, they can pick up the calls of Antarctic blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus intermedia), figure out their positions, and locate them for further study.

“This analysis represents the most contemporary circumpolar information on the distribution of these rarely sighted and elusive animals, which were hunted to the brink of extinction during industrial whaling,” says marine mammal acoustician Brian Miller, from the Australian Antarctic Program.

“We can reliably listen for [these whales], sail to them and visually sight them, then photograph and follow them, and even take small biopsies of their skin and blubber for further study.”

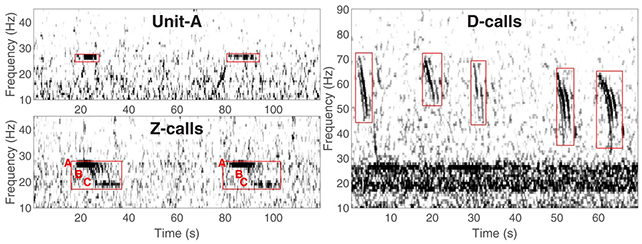

Three distinct loud and low-frequency calls were logged by the team, and two are only made by blue whales in this part of the ocean: the Z-call made only by the males, and the Unit-A call that’s a specific part of the Z-call.

The third call is the ‘social’ call known as the D-call, which is made by all blue whale populations, and by both male and female whales on feeding grounds. Studying the patterns of these calls helps to monitor whale populations over time.

“Unit-A was the most widely distributed call detected on the largest number of sonobuoys throughout the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic,” says Miller.

“We detected more of the non-song D-calls earlier in the summer feeding season, and the Unit-A and Z-song calls later in summer and early autumn.”

While we don’t know exactly what these calls mean, they can be combined with other data – like drone footage and AI algorithms – to assess the movements of blue whales and different aspects of the animal’s behavior.

As the planet adapts to climate change, the researchers are hoping that the techniques they’ve developed in this new study can be used to monitor the possible impacts on blue whale populations – and on krill, their major food source.

Further investigations could make use of uncrewed vehicles, fitted with hydrophones (underwater microphones) and other instruments to record calls and swim speeds – potentially linking different call types to different feeding patterns.

“Our analysis and the collated datasets will serve as a baseline and springboard for future work,” says Miller. “Passive acoustic monitoring is poised to play a crucial role in future research addressing knowledge gaps about Antarctic blue whales.”

The research has been published in Frontiers in Marine Science.