A cattle painkiller introduced in the 1990s led to the unexpected crash of India’s vulture populations, which still haven’t recovered to their former glory.

Some might have said ‘good riddance’ to this much-maligned, death-associated bird, but there’s a devastating human cost, and a new study reveals the shocking numbers, linking their absence to the deaths of over half a million people.

The analysis from the US and UK suggests human mortality in districts affected by vulture loss increased by more than 4 percent because of the sanitation ‘shock’ that ensued, causing an estimated US$69.4 billion in economic damages annually from 2000 to 2005.

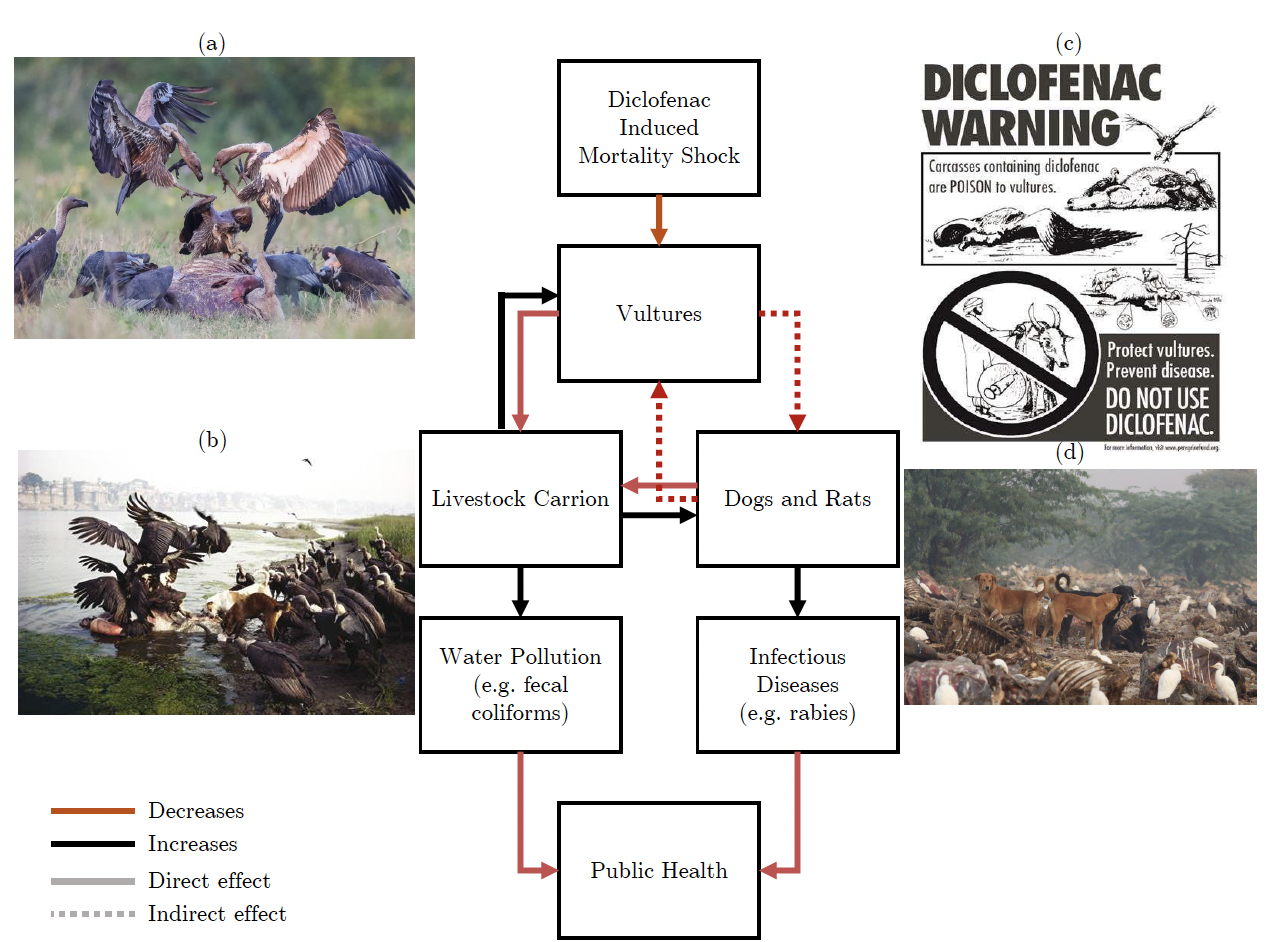

A thorough scavenger species, vultures’ meticulous feasting cleans carcasses down to the bone, leaving no muscle to rot, while others of their ilk – such as dogs and rats – are not only messy eaters, but disease carriers themselves.

Vultures can strip a cow skeleton in 40 minutes, and this efficiency led to their downfall once veterinary use of the drug diclofenac emerged in India in 1994. In just ten years after its introduction into the ecosystem, the vulture population plummeted from an estimated 50 million birds to a couple thousand.

Given to cattle to treat pain and inflammation, diclofenac remains in a cow’s system for around three days. Sick cows sometimes die before they metabolize the drug, and in areas without access to expensive animal incinerators, vultures have long offered their body disposal services to the agricultural sector.

But remnants of diclofenac in dead cows are poisonous to the raptors, whose kidneys become damaged. Unable to pass in their urine, uric acid builds up in the vulture’s blood, reaching up to ten times the normal level. Uric acid crystals are often found on the organs of vultures that died from exposure to diclofenac.

It wasn’t until several 2004 papers named diclofenac as the vulture’s vice that countries in South Asia began to ban its use in livestock. But the damage was already done, with this unlikely keystone species rendered functionally extinct in India.

Without vultures to literally pick up the pieces, disease spread via both decaying flesh, and a boom among other disease-carrying scavengers, like rabid dogs.

Environmental economists Eyal Frank, from the University of Chicago, and Anant Sudarshan, from the University of Warwick in the UK, set out to quantify the human toll of this ecosystem catastrophe.

In lieu of quality data on vulture numbers across the years, they overlaid data on vulture habitat from BirdLife International, drug sales in India between 1991 and 2003 (especially diclofenac and rabies vaccinations), human health outcomes from Vital Statistics of India, and livestock census data.

Districts affected by vulture loss were defined as those where suitable vulture habitat converged with diclofenac use in livestock, along with other ecosystem health factors like reduced water quality and high dog populations.

From 2000 to 2005, these districts had an average increase in all-cause human deaths of 4.7 percent – more than 100,000 extra deaths each year. Based on the India-specific value of statistical life, $665,000 per person, the yearly cost of human mortality was US$69.4 billion.

These impacts were not seen in districts that were not classified as reliant on vultures.

The authors hope that these somewhat brutal figures could push policymakers to act to protect essential species, like vultures, that are considered ‘dirty’ due to their association with death, but which provide ecosystem services that ultimately benefit human survival.

“Our results suggest that subjective existence values alone may not be the best way to formulate conservation policy,” Frank and Sudarshan write.

Headway has already been made, with veterinary drug alternatives like meloxicam and tolfenamic acid, which aren’t toxic to vultures, being used in place of diclofenac since it was banned in India in 2006.

However, other anti-inflammatory drugs such as ketoprofen, nimesulide, and aceclofenac are yet to be banned on a national level, despite studies showing these are similarly toxic to vultures.

The study has been accepted for publication in an upcoming edition of the American Economic Review. You can read the working paper online at the University of Chicago.