Last year a new discovery in particle physics stunned scientists: a fundamental particle responsible for one of the particles of the universe four basic forces was harder than predicted.

The discovery of a discrepancy between W boson‘s theorized and experimental masses promised new insights beyond the standard modelthe theoretical blueprint that describes how matter behaves.

Now scientists have recalculated the same numbers using an updated technique, but this time the discovery of the particle’s mass fits well with Standard Model predictions.

While this means we may not need to revolutionize our current theory of particle physics, we can’t help but be a little disappointed. However, the standard model of particle physics has so far remained a hypothetical interpretation of the universe around us it has held up well to the series of tests we put it through. At the same time, we know that there are inexplicable gaps: the Standard Model does not take this into account Dark matterfor example, or even gravity.

While the W boson cannot be measured directly, the mass and energy released on decay can be measured. Putting the pieces together requires a thoughtful approach and a solid starting point to knowing how collided particles hold together.

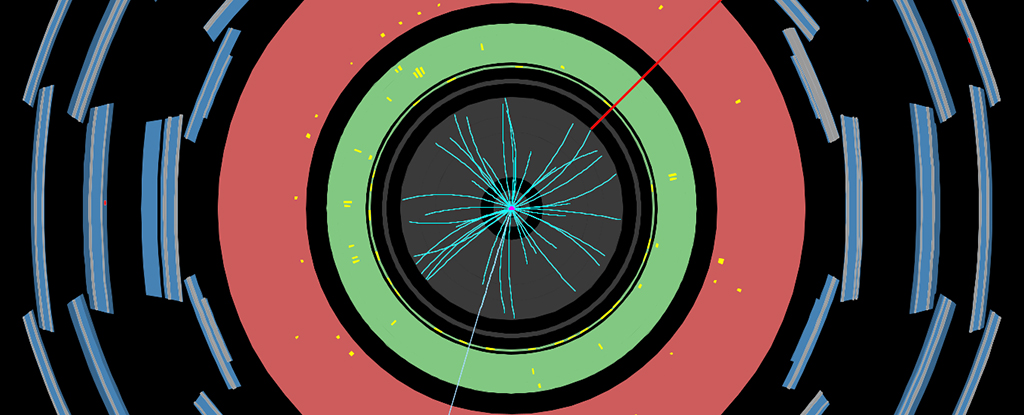

The latest research reanalyzed data from 2011 ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland using a revised statistical approach based on an improved understanding of the processes.

The researchers say their new reading is 16 percent more accurate than before and with a lower level of uncertainty, and question the 2022 results from the now-closed Tevatron collider in Illinois state.

“While the understanding of the detector and the impact of contributions from electroweak and top quark background processes have not changed, significant progress has been made in the statistical framework in extracting the W boson mass from the data.” write Researchers.

For this new research, the team focused on particle collision events in which the W boson breaks up into lighter particles: electrons, muons, and neutrinos. Additional data collected in 2017 helped validate the results.

The Tevatron measurement returned 80.4335 gigaelectronvolts, an apparently small but significant difference to the 80.357 gigaelectronvolts predicted by the Standard Model. The latest W boson mass measurement is 80,360 gigaelectronvolts, much closer to the theoretically predicted mass.

As a class of particles, measure bosons such as the W boson essentially facilitate interactions between other elementary particles. Along with the Z boson, the W boson is crucial in processes such as radioactive decay and nuclear fusion.

“Due to an unknown neutrino in the decay of the particle, the measurement of the W mass is one of the most demanding precision measurements that can be carried out at hadron accelerators”, says Particle physicist Andreas Hoecker from the ATLAS team in the CERN laboratory.

“It requires extremely accurate calibration of the measured particle energies and momenta, as well as careful evaluation and excellent control of the modeling uncertainties.”

It is worth bearing in mind that this is only a preliminary finding at the moment. Further tests with more recent data are now underway. If the Standard Model turns out to be wrong about the mass of the W boson, it would point to some previously undiscovered particles and forces at play. For now, however, the reputation of this fundamental hypothesis seems secure.

“This updated result from ATLAS provides a rigorous test and confirms the consistency of our theoretical understanding of electroweak interactions,” says hump.

You can read a paper detailing the new findings the CERN website.