When does a regular joke become a dad joke? As soon as it’s apparent.

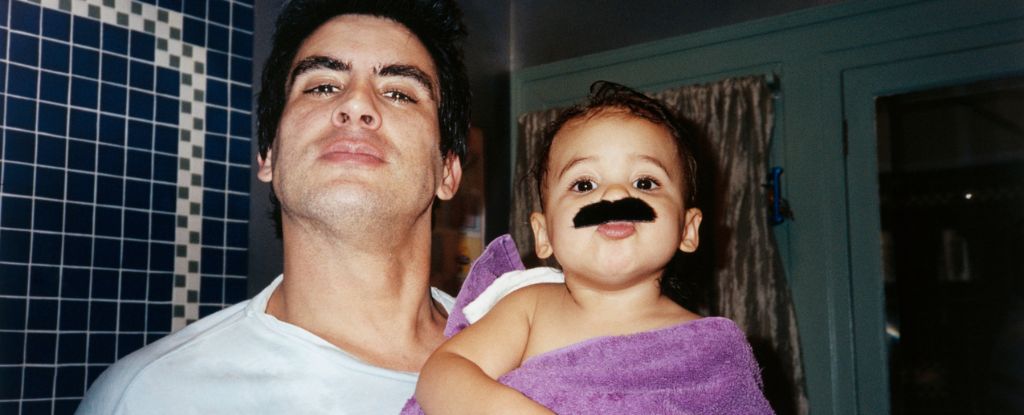

Hokey puns like that one are a quintessential form of “dad joke,” a term inspired by the common fatherly inclination for corny quips and cheesy wordplay.

Yet while dad jokes customarily elicit groans and eye rolls, the jocular attitude behind them may nonetheless help dads – as well as moms and parents/guardians in general – build better relationships with their kids, according to a new study.

The use of humor in parenting has received scant scientific investigation until now, the study’s authors say, despite the prevalence of humor in human social life and a wealth of literature on the topic in other fields of study.

Considering the findings from some of those earlier studies, our lack of knowledge about humor in parenting seems like an oversight worth correcting, the researchers say.

“Humor can teach people cognitive flexibility, relieve stress, and promote creative problem solving and resilience,” says senior author Benjamin Levi, pediatrician at Penn State College of Medicine.

“My father used humor and it was very effective. I use humor in my clinical practice and with my own children,” Levi says. “The question became, how does one constructively use humor?”

Previous research has looked at facets of humor and play in child development, as well as other contexts, the authors note, but the specific issue of humor’s role in parenting remains poorly understood.

Due to inherent child-parent power dynamics, humor might help families akin to the way research suggests it can help businesses, says first author Lucy Emery, who was a medical student at Penn State while working on the new study and is now a pediatrics resident at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“There’s an interesting parallel between business and parenting, which are both hierarchical,” Emery says.

“While parent-child relationships are more loving than business relationships, stressful situations happen a lot when parenting,” she adds. “Humor can help diffuse that tension and hierarchy and help both parties feel better about a stressful situation.”

With little existing research to build upon, Emery and her colleagues conducted a small pilot study to examine people’s views on the role of humor in parenting, including their experiences being parented, and their experiences as a parent.

This could be a jumping-off point for future research, the authors say, to explore in more detail how and when parents can use humor constructively.

For the new study, the researchers created a 10-item survey to measure a person’s experiences and opinions about humor and parenting, then used an online tool to find eligible participants.

They ended up with 312 respondents, aged 18 to 45, most of whom identified as male (63.6 percent) and White (76.6 percent).

More than half of all respondents said they were parented with humor as children, the survey found, and nearly 72 percent expressed belief in humor as an effective parenting technique.

Most reported using or planning to use humor with their own children, the researchers note, and most said they believe humor has more potential to help than to harm.

The survey responses also showed a correlation between parents’ use of humor and some relevant opinions their now-grown children express on the matter.

Participants who reported having a good relationship with their parents were 43 percent more likely to report that their parents had used humor in raising them compared to those who denied having a good relationship with their parents.

These individuals were also nearly 30 percent more likely to use humor or plan to use humor in parenting their own children.

It makes sense that people parented with humor would employ similar tactics for their kids, but the study’s authors didn’t expect such a dramatic difference between the two groups.

The study offers preliminary evidence that “Americans of childbearing/rearing age have positive views about humor as a parenting tool, and that such use of humor may be associated with various beneficial outcomes,” they write.

Future research, they add, should look at how parents use different kinds of humor, what that’s like for their kids, and how that fits with our existing knowledge about the social roles of humor.

“My hope is that people can learn to use humor as an effective parenting tool, not only to diffuse tension but develop resilience and cognitive and emotional flexibility in themselves and model it for their children,” Levi says.

The study was published in PLOS One.