Tattooing is an art that humans have been practicing for millennia. While 32 percent of adults in the United States have at least one, many of the inks in the United States today used to decorate people’s skin are more of a motley mixture than a precise blend, a new study has found.

Kelli Moseman, a chemistry researcher at Binghamton University in New York, and colleagues, analyzed more than 50 tattoo inks from nine different brands used in the US after noticing that some inks they had used in previous studies contained substances that weren’t listed on the label.

Testing inks made by global companies and smaller producers, the researchers found in their new analysis that 45 of the 54 inks they ran through chemical analyses contained substances that weren’t on the label, like unlisted pigments or additives. Some ink labels also listed additives that weren’t present: 36 listed glycerol but it was only detected in 29 of the inks.

Only one brand’s labels accurately listed the ingredients its ink contained. Fifteen inks contained propylene glycol, the American Contact Dermatitis Society’s 2018 allergen of the year, while other tested samples contained potentially harmful or simply strange substances, such as antibiotics.

It’s not yet known if these are accidental contaminations of tattoo inks, errors in labeling, or intentional but undisclosed additions; that would require further investigation.

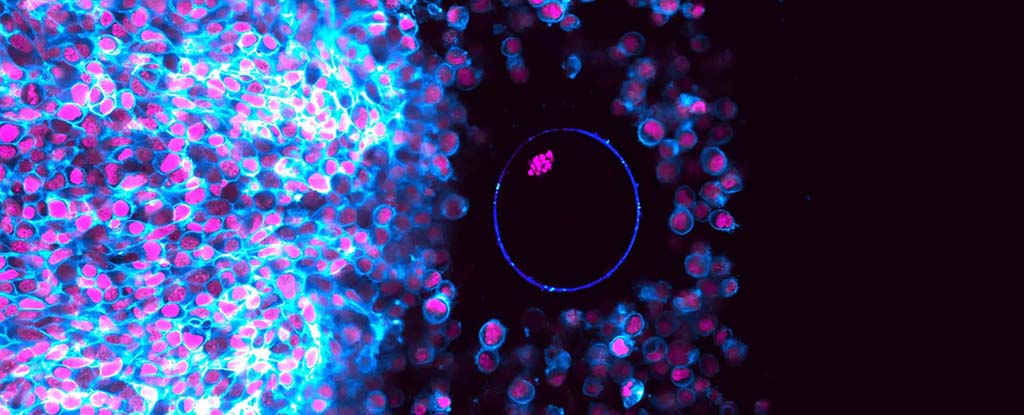

But given how long tattoo inks stay in the skin, their summons of immune cells, and evidence suggesting small amounts of pigment can leak into lymph nodes, the findings are concerning enough to warrant attention.

A 2021 study of tattoo inks used in the European Union also uncovered major issues with mislabeling and unlisted additives in a similar proportion of products (around 90 percent) while also detecting metal impurities at concentrations exceeding regulated limits.

“We’re hoping the manufacturers take this as an opportunity to reevaluate their processes, and that artists and clients take this as an opportunity to push for better labeling and manufacturing,” senior author and Binghamton University chemist John Swierk says.

Tattoo inks, especially red hues, can cause allergic reactions such as swelling, itching and blisters months or even years after they were first injected. But if ingredients aren’t listed on product labels, it makes it difficult to figure out what may have caused the reaction and prevent it from happening again.

Moseman and colleagues looked at both pigments in tattoo inks and substances used to suspend the pigments in solution, or modify the ink’s viscosity or surface tension.

The team used multiple analytical techniques to confirm the presence of unlisted substances. Raman and XRF spectroscopy allowed the researchers to identify the pigments in each ink while NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry were used to find out what was in the carrier solutions.

Detection limits for NMR spectroscopy meant the researchers focused only on substances present in the carrier solution at considerably high concentrations of 2,000 parts per million (ppm) or more, which means anything in lower concentrations may not have been observed.

The European Chemicals Agency, which introduced regulations in 2022 to restrict thousands of hazardous chemicals found in tattoo inks, considers substances down to concentrations as low as 2 ppm.

“While we are only considering six inks per manufacturer, there is reasonable cause for concern that labeling issues are likely to extend to other inks not considered in this study,” the researchers write in their paper.

Towards the end of 2022, the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) also moved to regulate tattoo inks as part of an expansion of its authority over cosmetics regulation. This change allows the FDA to recall products, if necessary, and requires that adverse events be reported and product ingredient labeling be updated yearly.

Since this kind of regulation is less than two years old, it’s not surprising that researchers are finding products containing ingredients not listed on labels. But these results can be used as a baseline to compare with the findings of future studies, to assess the impact of those regulations and ultimately improve safety.

The research has been published in Analytical Chemistry.