Contrary to what we may have assumed about the migration of modern humans out of Africa, at least some movement may have been driven, not by ‘green corridors‘, but by privation.

A new analysis involving volcanic glass found in Ethiopia reveals humans lived in what could have been drought conditions in the Horn of Africa 74,000 years ago, forcing them to adapt, and possibly travel, to maximize available resources.

Following seasonal rivers and waterholes, where food was more plentiful, could have created what a team of scientists calls ‘blue highways‘ that facilitated a dispersal out of Africa and into the big wide world.

“As people depleted food in and around a given dry season waterhole, they were likely forced to move to new waterholes,” says anthropologist John Kappelman of the University of Texas at Austin, who led the research.

“Seasonal rivers thus functioned as ‘pumps’ that siphoned populations out along the channels from one waterhole to another, potentially driving the most recent out-of-Africa dispersal.”

Humans and human ancestors are known to have migrated out of Africa many times in prehistory, and it seems a change in climate conditions is a very compelling reason to do so. But piecing together when and why humans en masse flowed out of Africa can be quite tricky.

The ‘green corridor’ theory proposes that, as food resources expanded and became bountiful, humans expanded with them. Kappelman and his colleagues sought to investigate an alternative driving force behind the most recent, and most widespread, migration, which occurred sometime less than 100,000 years ago.

Their research focused on the Shinfa-Metema 1 archaeological site in what is now northwestern Ethiopia, investigating how the people there lived. There, they found stone tools, the bones of the animals the people consumed, the remnants of their cooking fires – and microscopic shards of volcanic glass, known as cryptotephra, that match the chemistry of the Toba eruption.

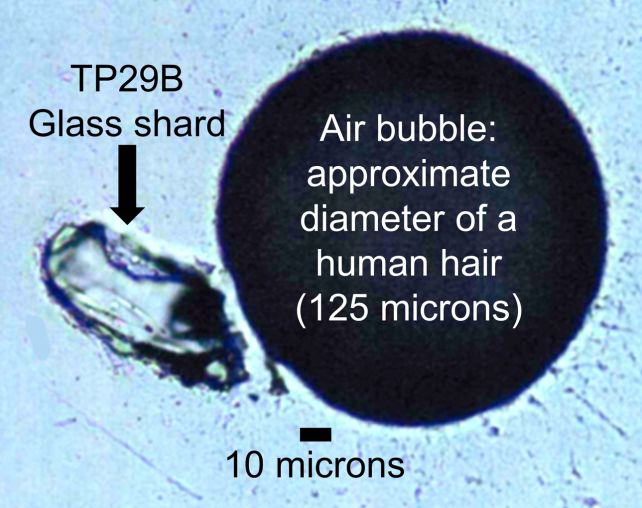

“One of the ground-breaking implications of this study,” says archaeologist Curtis Marean of Arizona State University, “is that with the new cryptotephra methods developed for our prior study in South Africa, and now applied here to Ethiopia, we can correlate sites across Africa, and perhaps the world, at a resolution of several weeks of time.”

Cryptotephra are smaller than the width of a human hair, but they can reveal a lot about human history. For example, cryptotephra can help reveal the extent of an eruption’s reach. Previous studies showed ash from the eruption in other parts of Africa. But they also help scientists pin down a date for archaeological artifacts.

In the case of Shinfa-Metema 1, the researchers gathered a collection of various types of evidence. Bones and teeth show the kinds of food the site’s inhabitants ate, with cut marks from hunting and butchery. They hunted and ate mammals such as monkeys and antelopes; when those resources became scarce, they relied more heavily on fish.

Interestingly, some of the stone artifacts found at the site are consistent with arrowheads. The researchers say this is the earliest evidence of archery found to date.

The researchers also conducted oxygen isotope analysis on mammal teeth and fragments of ostrich eggshells found at the site. The ratios they derived were consistent with a period of high aridity.

Although the people of Shinfa-Metema 1 were probably not among those migrating, they displayed a high level of adaptability in hard times, which suggests that humans were readily able to go with the flow, so to speak. That when times got tough, they found new ways to live, even if those ways may have meant finding greener pastures.

“This study confirms the results from Pinnacle Point in South Africa,” Marean says. “The eruption of Toba may have changed the environment in Africa, but people adapted and survived.”

The research has been published in Nature.