When the ‘wood-wide web’ was first described in the journal Nature in 1997, our view of plant life took on a utopian glean. But a new paper suggests this communication network between plants might not be so altruistic after all – and could even be used for sabotage.

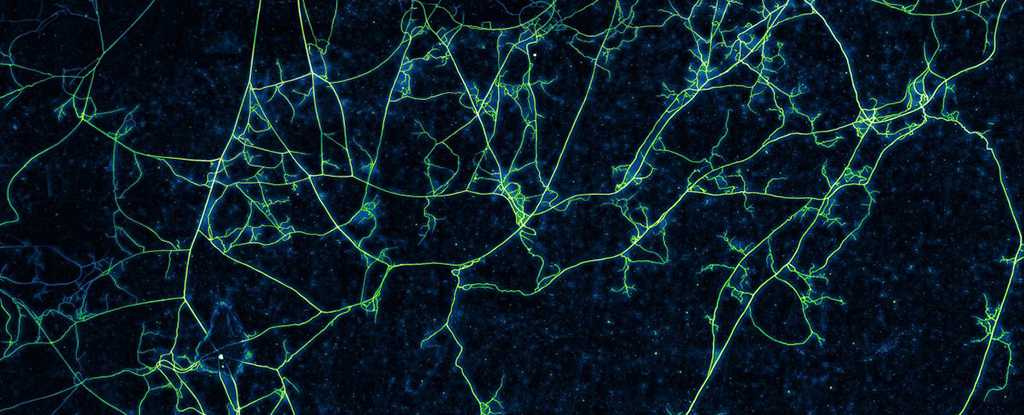

Plants can send and receive chemical signals, aided by the mycorrhizal fungal networks that connect their roots below ground. This phenomenon was described by forest ecologist Suzanne Simard and her colleagues nearly three decades ago, and is now known affectionately as the ‘wood-wide web’.

When a caterpillar takes a bite out of a tomato leaf, for instance, scientists have observed that a neighboring plant, connected to the first by a mycorrhizal network, will ramp up production of the bug-repellent enzymes in its genetic arsenal.

It’s easy to assume the plant under attack is actively emitting a warning signal to its neighbors, like a horror movie character stuck in a trap: “forget about me – save yourselves!” And that’s how many have interpreted this phenomenon.

But a trio of biologists from the University of Oxford and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU) suspect this view of plant communications may be a little too rosy.

“There is no dispute that information is transferred. Organisms are constantly detecting and processing information about their environment,” says VU evolutionary biologist Toby Kiers.

“The question is whether plants are actively sending signals to warn each other. Maybe just like gossiping neighbors, one plant is simply eavesdropping on the other.”

The team used mathematical models to unpick the possible evolutionary drivers of the supposed warning signal system.

It makes sense that plants might evolve to pick up on signs of distress among their kin and respond with defenses: the physical ability to do so helps them to ward off their own caterpillar attack before it even happens.

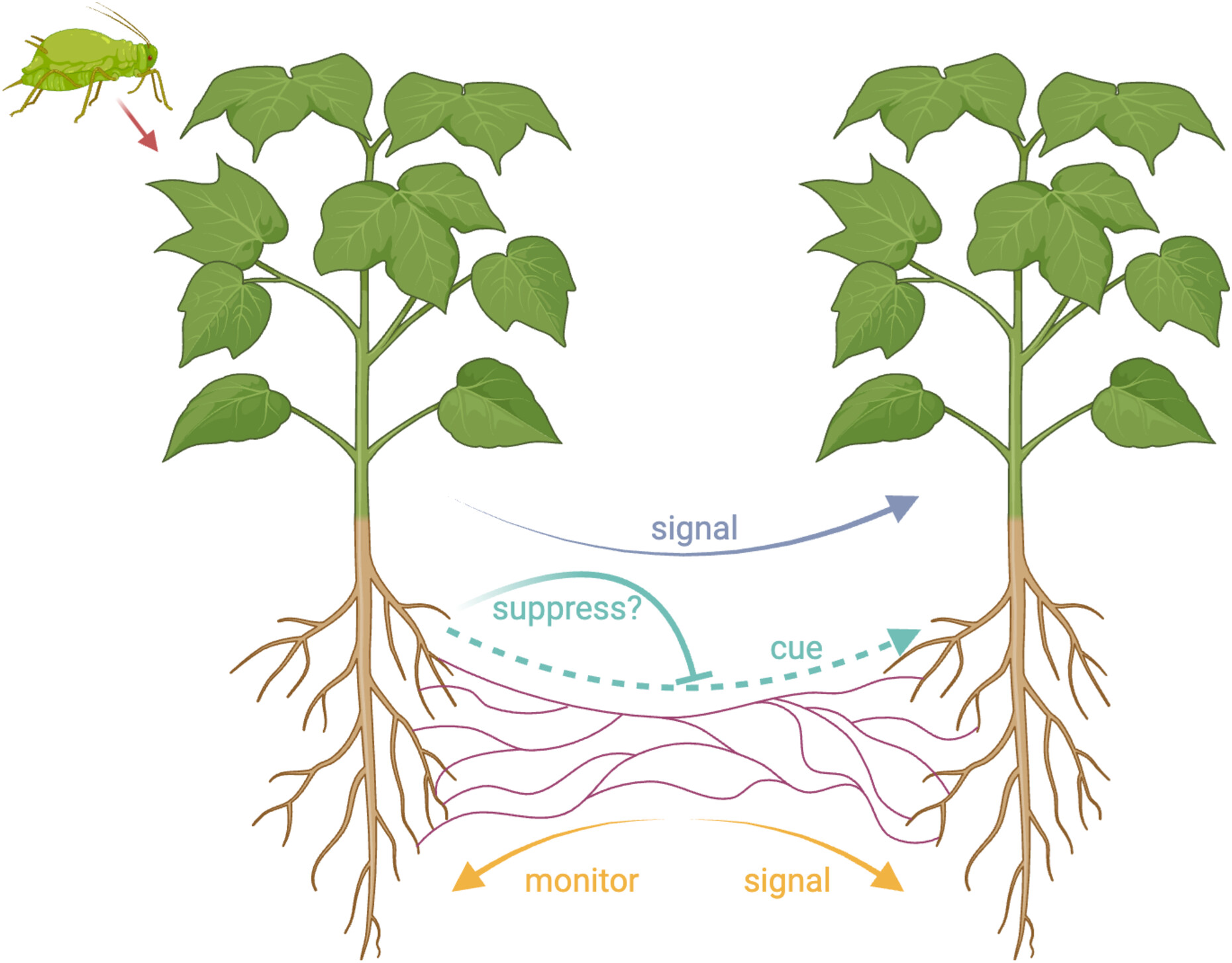

But the plant issuing that signal doesn’t necessarily benefit from this interaction. The team’s modeling showed that giving its neighbors such an advantage could actually do the plant more harm than good. Evolutionary pressures in their modeling, like competition with neighboring plants for nutrients and sunlight, actually selected against such an altruistic trait.

“Indeed, selection is often more likely to push plant behavior in the opposite direction – with plants signaling dishonestly about an attack that has not occurred, or suppressing a cue that they have been attacked,” the authors write.

“For instance, plants may signal that a herbivore attack is occurring, even when no herbivore is present,” says University of Oxford evolutionary theoretician Thomas Scott.

“Plants can gain a benefit from dishonest signaling because it harms their local competitors, by tricking them into investing in costly herbivore defense mechanisms.”

However, nature might select against crying caterpillar too often. If the lies are prolific enough, plants may stop ‘trusting’ messages from their neighbors altogether.

Either way, we still see examples of what is often interpreted as ‘honest signaling’ again and again in the plant world. Based on their models, the authors reason that there must be some other evolutionary benefit, besides altruism, at play.

One option is that it’s too difficult for a plant under siege to silence the chemical cry that inadvertently warns their neighbors of the attack at hand.

“For instance, in nature, it may be too costly or even impossible to suppress all cues of herbivore attack, given the sheer volume and diversity of such cues, passed through the air or fungal networks,” the authors write.

Another option is that the fungi – not the plants – are sending the warning signals, pulling the lever in a kind of subterranean trolley problem. They have a vested interest in ensuring the survival of as many host plants as possible, rather than protecting just one.

Perhaps, in a way, the ‘wood-wide web’ has more in common with our internet than we’d like to admit: it may also be beset by misinformation and selfish interests.

The new research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).