From France to Indonesia and Australia, ancient life is painted on the walls of dark caves, seemingly motionless silhouettes in earthy colors that reflect an earlier time.

But in recent years, archaeologists have envisioned how these simple images might have captured moving scenes in ways we might have overlooked. Apparently, animation has its roots in ancient works of art.

Earlier this year a series of Stone engravings of strange animals with fused bodies reignited speculation about the earliest forms of animation. Using 3D models and virtual reality software, the team of archaeologists bring ancient etchings to life argued that the stone artworks could have been dynamic depictions of animals in motion when viewed by firelight.

While they may be a far cry from the hyper-real animation that entertains us today, these prehistoric artworks are awe-inspiring – inasmuch as our human desire to understand, depict, and recreate movement runs deep.

Another specimen lay covered in ash and dust for centuries Shahr-e Sukhteh, an archaeological site in south-eastern Iran known as the “Burned City”. Here the researchers found a nondescript goblet with burnt red sketches of a leaping goat that springs to life when the vase is rotated – much like a modern one zoetrope of the 19th century.

In five consecutive frames, the horned goat jumps up to eat the leaves of a tree that could represent it Assyrian Tree of Life. But only archaeologists recognized the drawings as a series of images years after the vase was unearthed in 1967.

Dating suggests the clay vase currently on display at Iran’s National Museum is around 5,200 years old, with some claiming it may be one of the oldest examples of animation. While this may be debatable, at least Persian potters mastered early concepts of animation and persistence of vision long before 19th-century inventors put the two and two together.

“This suggests that humans have been fascinated by the movement of animals for thousands of years and have expended energy capturing a series of sequential images,” says Leila Honari, a Persian animator and art scholar at the University of Griffith in Australia. Write in the magazine of animation studies in 2018.

As Paleolithic and filmmaker Marc Azéma describes In a 2015 article, if we look closely, there are many more examples of Paleolithic artists bringing their artworks to life.

Sprawling, graphic, and often chaotic narrative scenes capture movement with repeated sequences. For example the Grand panneau of the Fond rooma hunting scene over 10 meters long (33 feet) found inside the Chauvet Cave in France, is full of horses and bison and features cave lions reappearing to hunt their prey along the wall. It has been dated to be around 32,000 years old.

In Indonesia, some 12,000 years earlier, people on the island of Sulawesi painted panoramic scenes stretching across limestone walls Depiction of supernatural beings bickering buffalo – in what is believed to be the oldest story ever found.

While these narrative performances are majestic, Honari writes that “the chalice of the burnt city indicates its creator’s knowledge of conceiving a series of images as a sequence of motion.”

“The old potter created ‘keyframes’ that incorporate a very basic level of now-classic animation principles like squash and stretch, anticipation and even timing and spacing” to create a vase that “must be the result of years of trial-and-error.” – Experiments”, Honari adds.

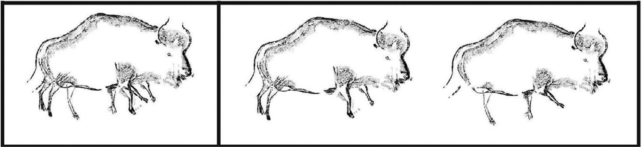

Split motion sketching was also used long ago to capture moving body parts. These works of art, like the stone engravings described earlier this year, overlay animal forms that at first glance appear to have a head or more legs than usual.

But as Azema explainedthose prehistoric drawings represent animals they gallop, toss their heads, or flick their tails—much like flip books. Sometimes barely sketched contour lines around the head or legs convey a sense of movement.

“An eight-legged bison drawn in the Alcôve des Lions in Chauvet Cave proves that split-action movement by superposition was already used by the Aurignacian [period]” about 35,000 years ago, Azéma writes. “This graphic illusion is most effective when the light from a grease lamp or torch is moved along the rock face.”

Ancient discs of bone and two-sided plaques with divided images of animals have also been found, likely used to create entertaining or symbolic visual illusions.

But regardless of the form or age of these works of art, they still tell a story that we can only remotely piece together. Animations aside, we can still marvel at ancient cave paintings Take viewers to other worlds long before our time and reorient our understanding about what it means to be human.