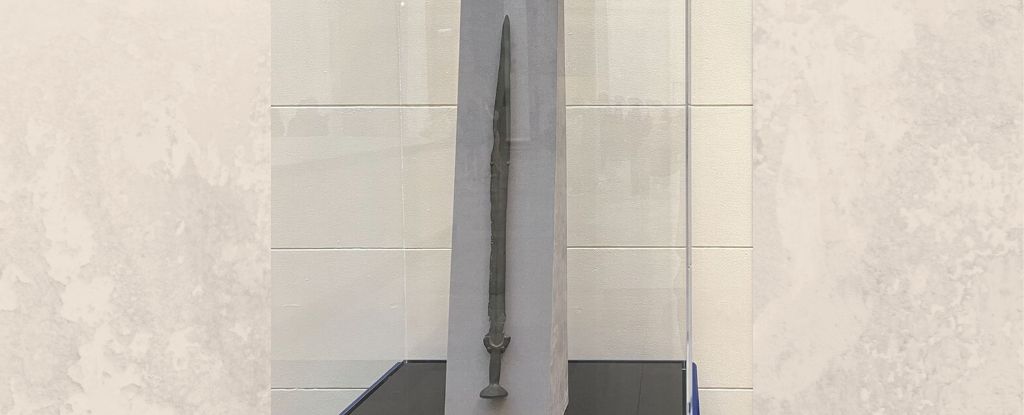

In the 1930s, a tarnished bronze sword was pulled from the banks of the Danube, which runs through Budapest.

It was designed like a Hungarian Bronze Age weapon, and yet it was thought to be a replica at the time, possibly made in the Middle Ages or later.

For almost a century the sword has been on display at the Field Museum in Chicago, marked as a mere copy. But last year, as the museum prepared for an upcoming exhibition on ancient European kings, a visiting Hungarian archaeologist (whose name has not been released) took one look at the sword and declared it genuine.

“We brought it out, he looked at it, and it was 20 seconds and he said, ‘It’s not a replica,'” said William Parkinson, curator of anthropology at the Field Museum. told a local news station.

But Parkinson wasn’t convinced yet. He wanted to use X-rays to see if the sword really was forged from the right copper and tin combinations, like other Bronze Age weapons from the region.

And “Bam!” Parkinson’s remindthe chemical composition of the sword matched that of other artifacts.

“Usually this story goes the other way around,” Parkinson said marveled in a recent press release from the museum. “What we think is an original turns out to be a fake.”

This way is much more exciting.

Experts now believe that the ancient sword was made somewhere between 1080 and 900 BC. It was thrown into the waters of the Danube for ritual purposes, possibly to commemorate a battle or the death of a loved one common lore among other cultures in Europe at that time.

The upcoming exhibition of the Field Museum, The first kings of Europescheduled to open in March 2023.

The newly authenticated sword will be the first artifact visitors to the exhibition will see upon entering the main hall – a replica that will no longer be overlooked.