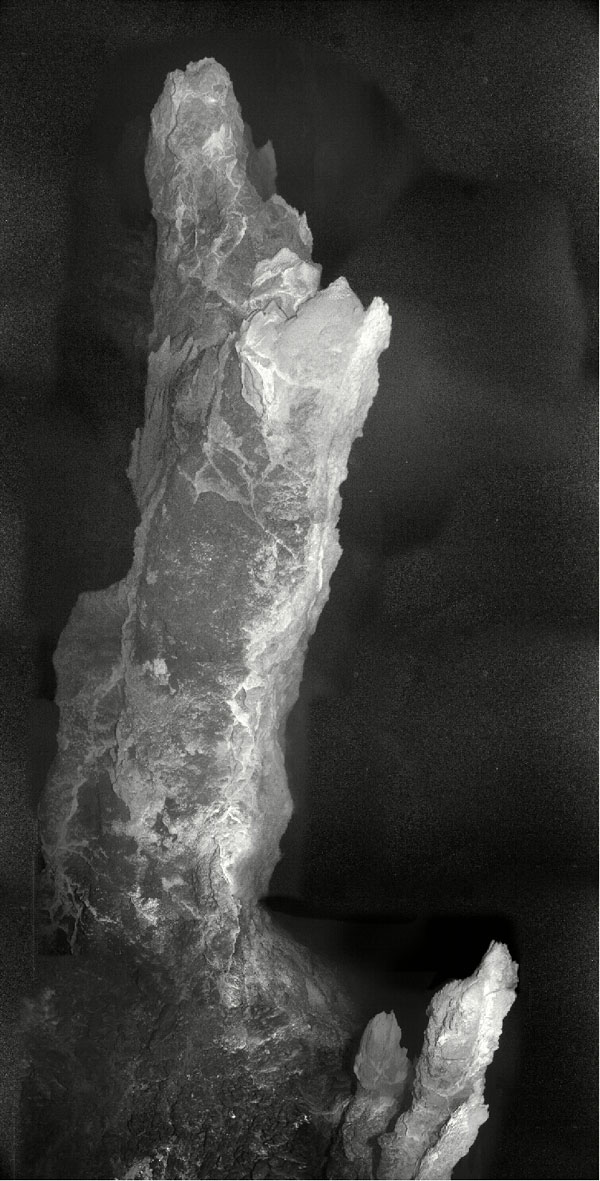

Near the summit of an underwater mountain west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a rugged landscape of towers rises out of the darkness.

Its creamy carbonate walls and pillars appear an eerie blue in the light of a remote-controlled vehicle sent to explore.

They range in height from tiny stacks the size of toadstools into a large monolith Standing 60 meters (nearly 200 feet) tall. This is the lost city.

Discovered by scientists in 2000 more than 700 meters (2,300 feet) below the surface, The Lost City hydrothermal field is the longest-lived known vent environment in the ocean. Nothing comparable has ever been found.

For at least 120,000 years and perhaps longer, the rising mantle in this part of the world has been reacting with seawater to blow hydrogen, methane, and other dissolved gases into the ocean.

In the cracks and crevices of the field’s chimneys, hydrocarbons feed novel microbial communities even without the presence of oxygen.

Chimneys that emit hot gases up to 40 °C (104F) home to an abundance of snails and crustaceans. Larger animals such as crabs, shrimp, sea urchins and eels are rare but still present.

Despite the extreme nature of the environment, it appears to be teeming with life, and researchers think it’s worth our attention and protection.

While other hydrothermal fields like this likely exist elsewhere in the world’s oceans, this is the only one that remote-controlled vehicles have been able to find so far.

The hydrocarbons produced by the vents of the Lost City were not formed from atmospheric carbon dioxide or sunlight, but from chemical reactions on the deep sea floor.

Since hydrocarbons are the building blocks of life, this leaves open the possibility that life originated in a habitat like this. And not just on our own planet.

“This is an example of an ecosystem that could be active on Enceladus or Europa right now,” said microbiologist William Brazelton told The Smithsonian in 2018, based on the moons of Saturn and Jupiter.

“And maybe Mars in the past.”

Other called underwater volcanic vents Black smokersalso mentioned as a possible first habitat, the ecosystem of the Lost City does not depend on the heat of the magma.

Black smokers primarily produce minerals rich in iron and sulfur, while the Lost City’s chimneys produce up to 100 times more hydrogen and methane.

The Lost City’s calcite vents are also much, much larger than black smokers, suggesting they’ve been around longer.

The tallest of the monoliths is named Poseidon, after the Greek god of the sea, and it rises over 60 meters high.

A little northeast of the tower is a cliff with short bursts of activity. Researchers at the University of Washington describe the openings here as “weeping” with fluid to produce “bundles of delicate, multi-pronged carbonate proliferations that extend outward like the fingers of upturned hands”.

Unfortunately, scientists aren’t the only ones drawn to this unusual terrain.

In 2018, it was announced that Poland had done so won the rights to mine the deep sea around The Lost City. While no valuable resources can be dredged in the actual thermal field itself, the destruction of the city’s surroundings could have unintended consequences.

This is the Lost City, a towering ecosystem in the middle of the North Atlantic. It is totally unique, with life found nowhere else on earth. And if someone wanted to destroy it? There’s nothing you can do about it. No Laws. No consequences. Welcome to the high seas… pic.twitter.com/mdG5wOsr5h

— Exploring the Open Ocean (@RebeccaRHelm) August 22, 2022

Any plumes or discharges triggered by mining could easily swamp the remarkable habitat, scientists warn.

Some experts are therefore support financially Inscribe the Lost City on the World Heritage List to protect the natural wonder before it’s too late.

For tens of thousands of years, the Lost City has been a testament to the enduring power of life.

It would be like us to ruin it.

A previous version of this article was published in August 2022.