Last year an ant species was caught using antibiotics – now, another has been observed performing amputations.

Researchers have just confirmed with experiments that this surgery and the other treatments ants provide each other do indeed save ant lives.

While we have known for a few years now that ants treat each other’s wounds, we’re only just learning how astonishingly complex and precise ant medical care can be.

“Ants are able to diagnose a wound, see if it’s infected or sterile, and treat it accordingly over long periods of time by other individuals,” explains behavioral ecologist Erik Frank from the University of Würzburg in Germany.

“The only medical system that can rival that would be the human one.”

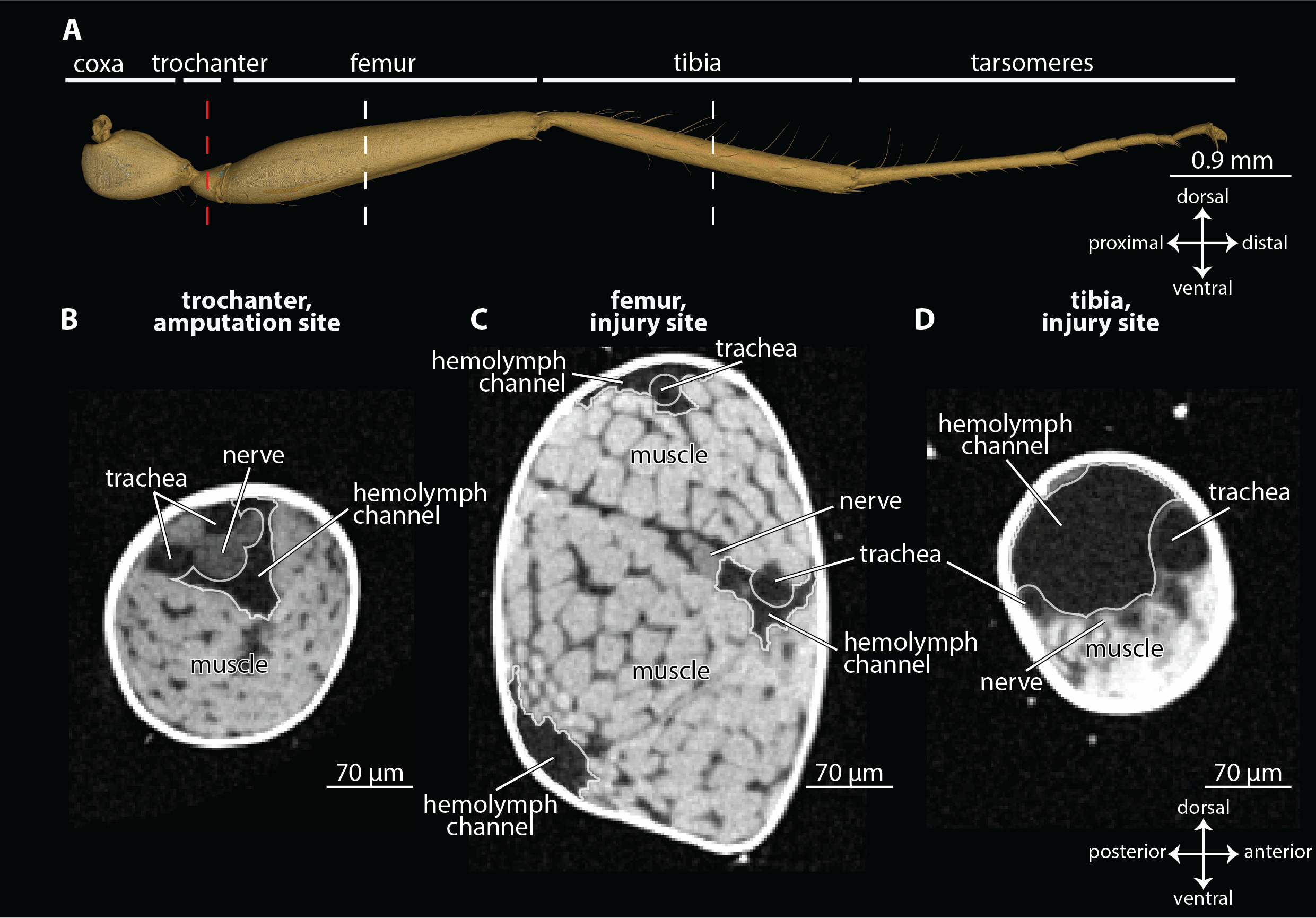

Frank and colleagues analyzed leg injuries in Florida carpenter ants (Camponotus floridanus). When wounds on the shin-like tibia were left unattended only 15 percent of the ants survived.

But if nestmates were allowed to tend to the wounds, injured ants’ survival rates increased to an incredible 75 percent.

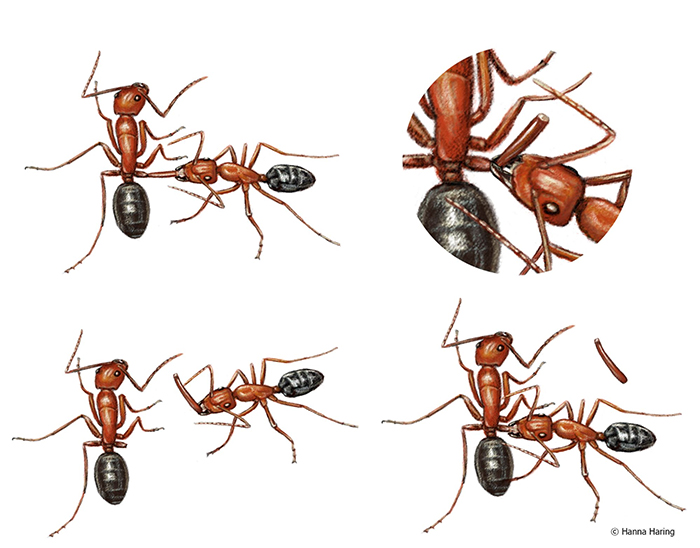

Tibia wounds were treated with mouth cleaning, in which the treating ant held the delicate injured limb with its mandibles and front legs, licking the wound for extended periods.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

But when the carpenter ants encountered nestmates with injuries on what would be equivalent to our thighs, the tiny surgeons first cleaned the wound before amputating the leg. This involved repeatedly biting the injured limb until it was severed.

The survival rate increased from 40 percent for ants with untreated femur wounds to about 90 percent after amputation.

Yet, the ants never amputated legs with wounds near the tibia. So Frank and team experimentally amputated tibia-injured ant limbs to find these ants’ survival did not increase.

“In tibia injuries, the flow of the hemolymph was less impeded, meaning bacteria could enter the body faster. While in femur injuries the speed of the blood circulation in the leg was slowed down,” says Frank.

It takes ants 40 minutes to complete a surgical amputation on a nestmate’s leg.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

“Thus, because they are unable to cut the leg sufficiently quickly to prevent the spread of harmful bacteria, ants try to limit the probability of lethal infection by spending more time cleaning the tibia wound,” explains evolutionary biologist Laurent Keller from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland.

Infections are a major threat to animals, particularly in social species where the risk of transmission is increased by close-quarter living.

Insects are known to mitigate some of these risks by destroying infected broods or leaving the nest to die in isolation.

Medical care of nestmates is likely another of these strategies, but how it arose in ants is an intriguing question, given there’s little evidence they can learn. This suggests such behavior may be innate, despite its complexity, the researchers suspect, but they are keen to experiment further to find out more.

“When you look at the videos where you have the ant presenting the injured leg and letting the other one bite off completely voluntarily, and then present the newly made wound so another one can finish [the] cleaning process – this level of innate cooperation to me is quite striking,” says Frank.

This research was published in Current Biology.