Masses of rock and other material swirl around our solar system as asteroids and comets. If one of these came towards us, we were able to successfully prevent the collision between one asteroid and earth?

Perhaps. But there seems to be one type of asteroid that could be particularly difficult to destroy.

Asteroids are boulders in space, remnants of a more violent past in our solar system. Examining them can reveal their physical properties, clues to the ancient history of the solar system, and threats these space rocks may pose from impacting Earth.

In our new study published today in which Proceedings of the National Academy of Scienceswe discovered that debris pile asteroids are an extremely resilient type of asteroid and are difficult to destroy through collisions.

Two main types of asteroids

Mainly concentrated in the asteroid belt, asteroids can be classified into two main types.

When people think of asteroids, they usually think of monoliths, which are made out of a solid boulder.

Monolithic-type asteroids, about a kilometer in diameter, have only been projected to have a life expectancy of 1000 a few hundred million years in the asteroid belt. Given the age of our solar system, that’s not all that long.

The other kind are Debris heaps of asteroids. These consist entirely of many fragments ejected during the total or partial destruction of pre-existing monolithic asteroids.

However, we don’t really know the durability, and therefore the potential lifetime, of debris pile asteroids.

Sneaky and plenty of debris

September 2022, NASA’s DART mission (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) successfully hit the asteroid dimorphos. The goal of this mission was to test whether we could deflect an asteroid by hitting it with a small spacecraft, and it was a resounding success.

Like other recent asteroid missions the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to visit asteroids Itokawa and Ryuguand from NASA to the asteroid BennuClose-up photos have revealed that Dimorphos is another debris-pile asteroid.

These missions showed us that debris pile asteroids have low densities because they are porous. In addition, they are plentiful. Indeed they are very are plentiful, and because they are shattered pieces of monolithic asteroids, they are relatively small and therefore difficult to see from Earth.

Therefore, such asteroids pose a major threat to Earth and we really need to understand them better.

Learn from asteroid dust

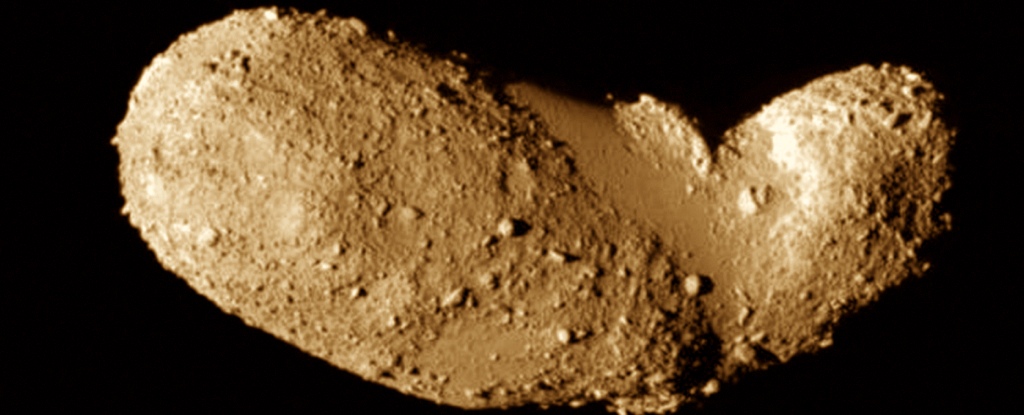

In 2010, the JAXA-designed Hayabusa spacecraft returned from the 535-meter-long, peanut-shaped Asteroid Itokawa. The probe brought with it more than a thousand rock particles, each smaller than a grain of sand. These were the very first samples to be brought back from an asteroid!

As it turned out, the images taken by the Hayabusa spacecraft while it was still orbiting Itokawa showed the existence of debris-pile asteroids for the first time.

Early results from the team at JAXA that analyzed the returned samples showed that Itokawa formed after the complete destruction of a parent asteroid, which was at least 20 kilometers in size.

In our new study, we analyzed several dust particles reflected from the asteroid Itokawa using two techniques: the first fires a beam of electrons at the particle and detects electrons that are scattered back. It tells us if a rock has been rocked by a meteorite impact.

The second is called Argon-argon dating and uses a laser beam to measure how much radioactive decay has taken place in a crystal. It gives us the age of such a meteorite impact.

Huge space pillows that last forever

Our results showed that the massive impact that destroyed the Itokawa parent asteroid and formed Itokawa occurred more than 4.2 billion years ago, almost as old as the solar system itself.

This result was completely unexpected. It also means Itokawa has survived almost an order of magnitude longer than its monolithic counterparts.

Such an amazingly long survival time for an asteroid is attributed to its shock-absorbing nature. Being a rubble pile, Itokawa is about 40 percent porous.

In other words, almost half of it is voids, so constant collisions simply crush the gaps between the rocks, rather than breaking apart the rocks themselves.

So Itokawa is like a giant space cushion.

This result suggests that debris pile asteroids are much more common in the asteroid belt than we once thought. Once formed, they seem very difficult to destroy.

This information is crucial to prevent a possible asteroid collision with Earth. While the DART mission successfully nudged the orbit of its targeted asteroid, the transfer of kinetic energy between a small spacecraft and a debris-pile asteroid is very small. This means they don’t inherently fall apart when bumped.

So if there were an immediate and unforeseen threat to Earth in the form of an approaching asteroid, we would like a more aggressive approach.

For example, we may need to use the shockwave from a nuclear explosion in space, since large explosions would be able to transfer much more kinetic energy to a naturally padded asteroid of debris piles, thus knocking it away.

So should we actually test a nuclear shock wave approach? That’s a whole different question.![]()

Fred JourdanProfessor, Curtin University and Nick TimmsAssociate Professor, Curtin University

This article is republished by The conversation under a Creative Commons license. read this original article.