If you’re scientifically minded, you might not think much of horoscopes and their predictions of your fated future, even if they are based on the positions of stars and planets in the sky on the night you were born.

Some squid, however, seem destined to become sneaky or aggressive mating partners depending on when they hatched, according to new research from Japan.

University of Tokyo marine biologist Shota Hosono and colleagues studied Japanese spear squid (Heterololigo bleekeri) and found that males’ reproductive tactics depend on which month they hatch.

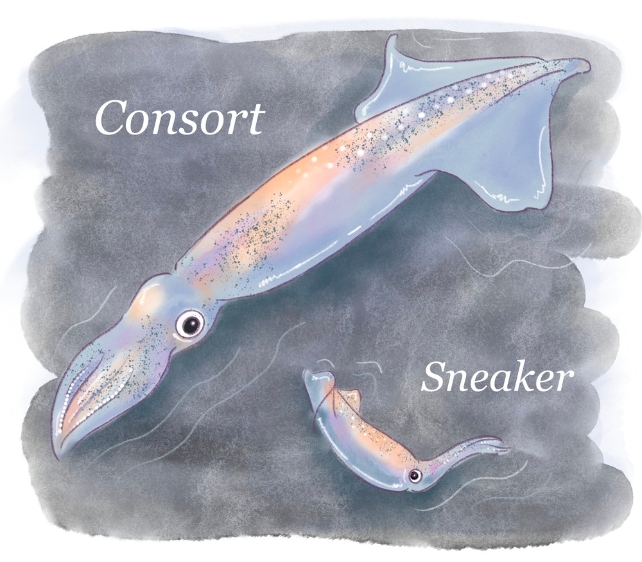

Squid hatching early in the breeding season, between early April and mid-July, had grown comparatively larger by mating time, so became consorts: squid that fight off rivals to impregnate a female and then guard her while she lays her eggs.

Squid that hatched later, between early June and mid-August, were typically smaller and became ‘sneakers’ – covertly depositing their sperm on the outside of a female near where she lays her eggs, in the hope of fertilizing them.

Those that hatched early July had an even chance of being a sneaker or a fighter.

This phenomenon is called the relative age effect, and can be seen clearly in the way that children born earlier in the year have a better chance of becoming professional athletes than others in their age group because they have more time to develop before selection.

However, before this squid study, this ‘birthdate hypothesis’ – as it’s otherwise known among biologists – had been tested only in several species of teleost fish, and no other taxonomic group in the broader realms of the animal kingdom other than humans.

“Typically, large males adopt a tactic of competing with rivals for mating, while small males adopt a tactic of stealing fertilization opportunities from the large males,” Hosono and colleagues explain in their published paper, after studying 201 male squids and 68 mature females.

This is the first time that evidence of the ‘birthdate hypothesis’ has been found in aquatic invertebrates, suggesting that male H. bleekeri are locked into mating behaviors from birth.

Even when male squid born early in the season failed to brawn up as expected, they didn’t buck the birthday trend and go the sneak approach; they’d postpone mating altogether and continue growing until they were large enough to be a consort.

“Our results showed that the hatching date determines the whole life trajectory in this species,” says Yoko Iwata, a marine ecologist at the University of Tokyo.

Moreover, these mating tactics aren’t simply inherited from their paternal line, Hosono, Iwata and colleagues reason.

“Female squid store sperm from both consort and sneaker males throughout the breeding season and use a mixture of sperm from both sources to fertilize their eggs during a spawning event,” the researchers explain.

Genetic variation stemming from alternative reproductive tactics can influence the mating behaviors of animals, including birds and damselflies, although documented examples of this are considered rare.

But Hosono and colleagues’ findings suggest that male mating tactics of H. bleekeri are likely determined by a heady mix of physical, biological, and environmental factors at birth. In beetles, for example, food availability is a key driver of physical traits linked to their sexual success in later life.

This seasonality is seen in humans too: the season in which you were born leaves its stamp on your DNA, affecting the odds you’ll have allergies for example.

“The difference in hatch date means that the squid experience different environmental conditions in early life, which may influence the growth trajectory,” Iwata says.

Squid are very sensitive to environmental conditions, particularly water temperature. Iwata says that if an extreme event, such as a marine heatwave, happened during their hatching season, it could affect the squid’s mature body size and subsequent mating tactic.

“This would also impact the amount that could be commercially caught enormously,” Iwata adds.

However, the study found that the growth rate early in life was not so different between consorts and sneakers, even though they grew up during different seasons, so further study is needed to untangle how environmental factors may affect mating behaviors in squid.

The study has been published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.