Predicted over a century ago as monstrous mass concentrations torturing the fabric of the universe in traps of light and information, black holes are now established as objects of fact.

But could every distortion of light we encounter now be a certified concentration of infinite density, or should we leave room for the possibility that other exotic types of cosmic oddities might also look eerily like a hole in space?

Obtained with mathematical modeling for string theorya trio of physicists from Johns Hopkins University in the US found that some objects that look like black holes from afar might be something very different up close: a new type of hypothetical exotic star called a topological soliton.

Given that string theory is a hypothesis begging for a remedy to be tested, these strange objects exist only on paper, floating around in the realm of pure mathematics. At least as far as we know. But even as a theoretical construct, they could one day help us distinguish true black holes from imposters.

“How would you know if you didn’t have one black hole? We don’t have a good way of testing that,” says the physicist Ibrahima Bah. “Studying hypothetical objects like topological solitons will help us figure that out.”

Black holes are arguably the most mysterious known objects in the universe. Hell, we didn’t even have concrete confirmation of their existence until First detection of gravitational waves in 2015, less than 10 years ago. That’s because black holes are so dense that their gravity distorts spacetime around them so much that within a certain distance known as the event horizon, nothing in the universe travels fast enough to reach escape velocity. Not even light in a vacuum.

This means that black holes don’t emit any light that we can currently see, making them, well, invisible; and since light is the most important tool in our kit for understanding the universe, we can really only learn about them by studying the space around them.

The black hole itself is mathematically described as a one-dimensional point of infinite density – something that doesn’t really equate to anything meaningful in physics.

But we can think of other bizarre manifestations of physics that behave similarly. An example is boson starshypothetical objects that are transparent and therefore invisible, just like black holes.

Now the small group around the physicist Pierre Heidmann has discovered that topological solitons represent a different one. These are a type of gravitational kinks in four-dimensional spacetime predicted by string theory, in which the smallest elements of the universe are not pixelated dots, but tiny vibrating strings.

From a distance, the surroundings of these kinks are not that unusual. Up close, however, the topology of space is severely distorted.

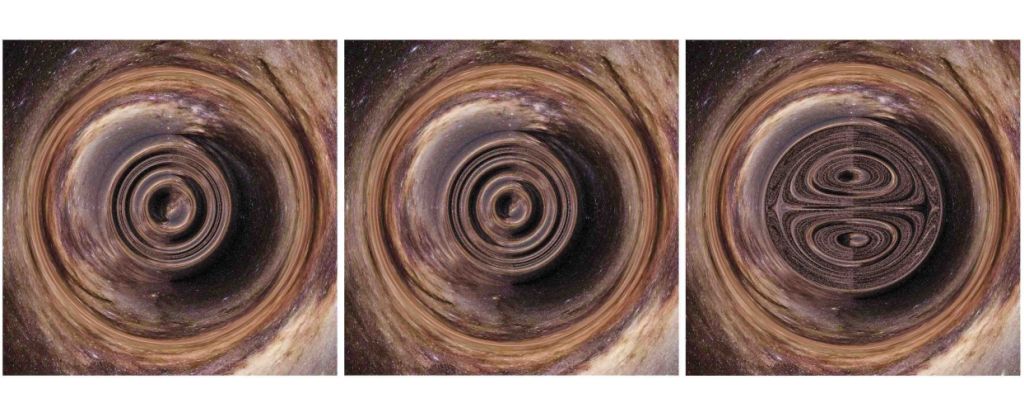

The team constructed their topological soliton mathematically, then fitted their equations into simulations to see how it would perform. They overlaid the simulations with real images of space to get the most accurate understanding possible of how their construct would behave.

From a distance, the topological soliton looked exactly like a black hole whose light seemed to be swallowed up.

However, at closer proximity, the topological soliton became strange. It didn’t capture any light at all like a black hole would, but instead encoded it and sent it out again.

“Light bends a lot, but instead of being absorbed like in a black hole, it scatters in crazy motions until at one point it comes back to you in a chaotic way.” says Heideman. “You don’t see a dark spot. You see a lot of blur, which means the light is spinning like crazy around this strange object.”

String theory is an attempt to resolve a long-standing and vexing tension in physics: between quantum mechanics, which describes how things behave on very small scales, and general relativity, which describes the larger scales. Quantum mechanics breaks down on relativity scales and vice versa, which bothers physicists to no end because they should can play well together.

A unified theory of the two, what we call quantum gravity, has proven elusive. The topological soliton is the first string theory-based object that conforms to black hole behavior, showing that quantum gravity objects can be used to describe real-world physics.

“These are the first simulations of astrophysically relevant string theory objects, as we can actually characterize the differences between a topological soliton and a black hole as if an observer saw them in the sky.” explains Heidemann.

We don’t expect to see them in the sky, of course, but studying the possibilities could help scientists better understand the tension between quantum mechanics and general relativity, hoping to one day lead us to a solution.

“This is the beginning of a wonderful research program,” Says Bah. “We hope that in the future we can propose truly new types of ultracompact stars composed of new types of quantum-gravity matter.”

The research was accepted Physical Check D.