The nearest single star to the Solar System has just yielded up a rare and wonderful treasure.

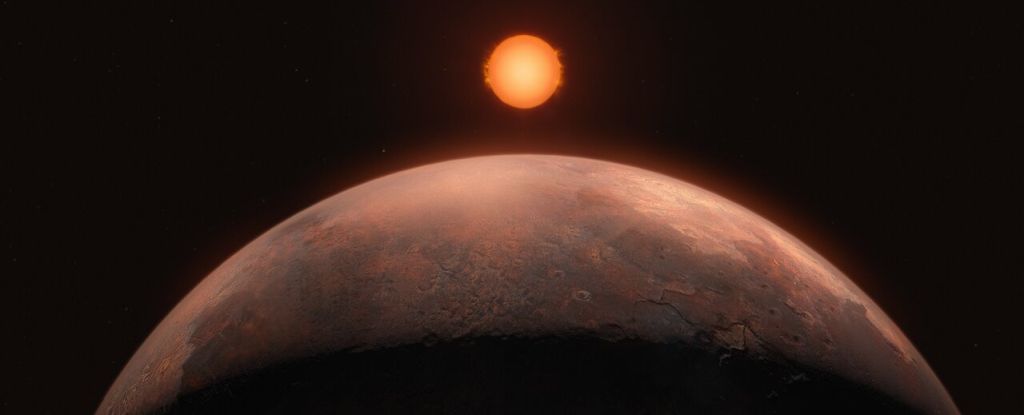

Around a red dwarf known as Barnard’s star, which lies just 5.96 light-years away, astronomers have found evidence of an exoplanet.

And not just any exoplanet. This fascinating world, known as Barnard b, is tiny, clocking in with a minimum mass of 37 percent of the mass of Earth. That’s a little shy of half a Venus, and about 2.5 Marses.

The reason it’s so marvelous is that tiny exoplanets are really, really hard to find. Although Barnard b is not habitable to life as we know it, its discovery is leading us closer to the identification of Earth-sized worlds that may be scattered elsewhere throughout the galaxy.

The discovery follows hints of a possible planetary signal orbiting the star in 2018. That hypothesized exoplanet was thought to be around three times the mass of Earth, orbiting at a distance of about 0.4 astronomical units.

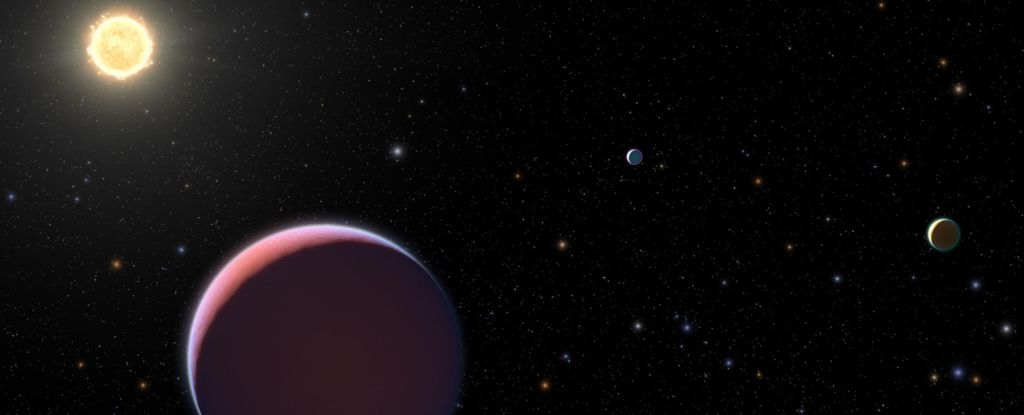

Though any planet matching that mass or distance is yet to be confirmed, the more teensy Barnard b emerged after researchers conducted a careful campaign to observe the star. What’s more, there might be three more exoplanets lurking even further from the star, out where they’re harder to spot.

“Even if it took a long time,” says astronomer Jonay González Hernández of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands in Spain, “we were always confident that we could find something.”

Barnard’s Star, also known as GJ 699, is of intense interest to planetary astronomers. The only stars closer to Earth are the Centauri trinary system. Barnard’s star isn’t just a lone star, like the Sun; it’s a red dwarf, the most common type of star in the galaxy. Studying it can tell us a lot about our galactic neighborhood and the planets there, planetary systems around single stars, and planetary systems around red dwarfs, and how habitable they might be.

Finding small exoplanets is a lot harder than finding the large ones. We find exoplanets mostly by identifying the effect they have on their host stars; the larger the exoplanet, the more prominent the effect.

If a star is smaller, though – like a small red dwarf, for instance – we can detect the signals of a smaller exoplanet than we would be able to for a larger star. And Barnard’s star is close, which means it’s easier to see than a star much farther away and therefore dimmer.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

The researchers used the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope to look for signs of radial velocity. That’s a signal that can be observed when a star moves around the mutual center of gravity it shares with an orbiting exoplanet. As the star wiggles slightly, the light it emits changes wavelength accordingly.

Astronomers can analyze this light and use it to work out if there is an exoplanet there, and how much mass that exoplanet has – since its mass informs how much the star wiggles.

Their data for Barnard’s star showed no signs of the exoplanet detected back in 2018. But it does show a wiggle with a periodicity of 3.15 days. That suggests an exoplanet that goes around the star every 3.15 days. The depth of the wiggle suggests that the mass of that exoplanet, now known as Barnard b, is at minimum around 0.37 times the mass of Earth.

On such a short orbit, the exoplanet is very close to the star, just 0.02 astronomical units. Although red dwarf stars are cooler and dimmer than the Sun, that’s still too close to the star to allow any life as we know it to exist.

“Barnard b is one of the lowest-mass exoplanets known and one of the few known with a mass less than that of Earth. But the planet is too close to the host star, closer than the habitable zone,” González Hernández says. “Even if the star is about 2500 degrees cooler than our Sun, it is too hot there to maintain liquid water on the surface.”

But that doesn’t mean that the system as a whole is uninhabitable. The data showed hints that three other exoplanets may be orbiting Barnard’s star, at greater distances than Barnard b. These signals are also faint, and more observations will be needed to confirm whether they are caused by orbiting exoplanets or something else.

“We now need to continue observing this star to confirm the other candidate signals,” says astronomer Alejandro Suárez Mascareño of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands.

“But the discovery of this planet, along with other previous discoveries such as Proxima b and d, shows that our cosmic backyard is full of low-mass planets.”

Maybe we should drop them a text message. It’s nice to be neighborly.

The research has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.