Wisdom teeth are the third set of molars located at the very back of the mouth. They look just like the first and second molars, but can sometimes be a little smaller.

They are commonly called wisdom teeth because they are the last of the 32 permanent teeth to appear, emerging between 17 and 25 years of age, when you are older and wiser.

You might know that not everyone grows all four wisdom teeth. You might also know many people get them pulled. So it’s fair to wonder – why do humans even have them?

We study teeth and can tell you the answer has a lot to do with the distant past – and a bit about the present day, too.

More powerful jaws

Just like you have many features in common with the people you’re related to, humans share features with their extended family – the primates. Monkeys, gorillas and chimpanzees all have wisdom teeth.

A few million years ago, early human ancestors had larger jaws and teeth than humans do today. For example, a species called Australopithecus afarensis, nicknamed Lucy’s species after a famous fossil specimen called Lucy, lived roughly 3 million to 4 million years ago.

The jaw and teeth of an Australopithecus afarensis individual were quite a bit larger and thicker than your own. They had three big molar teeth with thick enamel. The fossil skulls of some of these very early humans also show evidence of powerful chewing muscles.

Changes in diet

Scientists think more robust jaws and teeth were needed because the foods early human ancestors ate, like raw meat and plants, were much more difficult to chew than food is today.

Researchers look at things like marks and microscopic wear patterns on fossilized teeth to figure out what extinct ancestors may have eaten.

Today’s food is much softer than it was in the past due to many factors, including agriculture, cooking and food storage. Softer, easier-to-chew food means teeth have a less challenging job.

As a result, modern human jaws have evolved to be smaller and faces to be flatter than our extinct ancestors’ were, because our meals don’t require the same big, sharp teeth that theirs did.

Given these changes, which took place very slowly over millions of years, the third molars – wisdom teeth – might not be as important now as they once were.

Missing wisdom teeth

About 25% of people today are missing at least one wisdom tooth completely, meaning it never formed at all. While people occasionally don’t grow other teeth, it’s much more common for wisdom teeth.

Scientists are not sure why this is the case, but it may have to do with the genes you inherit from your parents. Some scientists have argued that the lack of wisdom teeth is an advantage for modern, smaller-jawed humans. It’s certainly easier to fit fewer teeth into a smaller jaw.

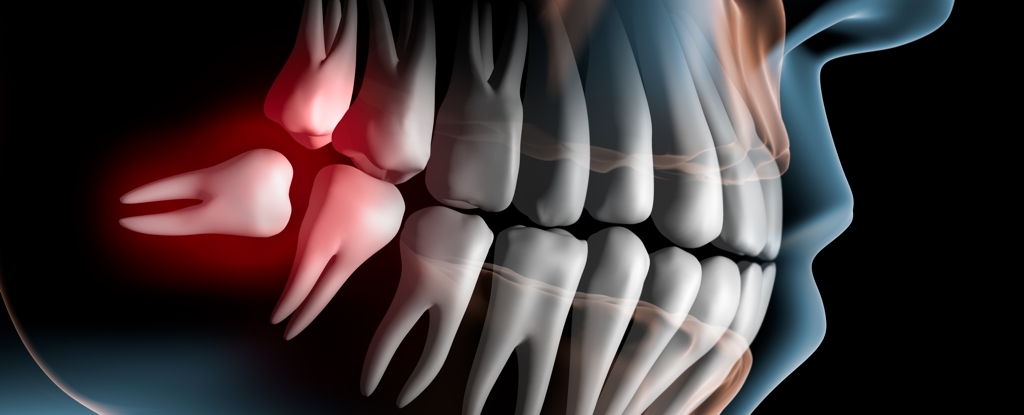

Sometimes, due to lack of space, wisdom teeth can get stuck inside the jawbone and never fully come up – or they only partially emerge.

A so-called impacted wisdom tooth happens more often in the lower jaw than in the upper jaw. In cases where wisdom teeth are only partially up, people can sometimes experience pain, tooth decay or gum inflammation, which is why they have them pulled by a dentist.

But wisdom teeth don’t usually need to be removed if they are fully erupted in the mouth, positioned correctly and healthy.

Dentists can examine your mouth to see if your wisdom teeth are present, or look at X-ray pictures of your jaw if these last molars haven’t yet emerged and you suspect they may be impacted.

Dentists can also advise you if any treatment – or removal – is recommended for your wisdom teeth. In the meantime, brushing at least twice a day and flossing daily will help keep all your teeth healthy.![]()

Ariadne Letra, Professor of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh and Seth M. Weinberg, Professor of Oral and Craniofacial Sciences and Human Genetics, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.