When things get tough in adulthood, it might seem appealing to return to simpler times.

One bizarre marine creature has taken this approach to dire situations quite literally, regressing its physical adult body to a juvenile stage once the stress of starvation or injury has subsided.

Until now, the immortal jellyfish (Turritopsis dohrnii) was the only species thought to be able to wind back the clock on jelly-puberty like this, but now it’s joined by Mnemiopsis leidyi, better known as the sea walnut or the warty comb jelly.

We already knew comb jellies were pretty special: Their regeneration abilities are unmatched, they can fuse together to survive major injuries, they only form a butthole when they actually need it, and with total disregard for the usual rules of biology, they can reproduce sexually in their so-called larval stage.

Previous studies had also observed M. leidyi reducing its size and body mass considerably during starvation as a way of surviving leaner times, but experiments ruled out reverse-aging under these conditions.

Marine biologist Joan Soto-Angel, from the University of Bergen in Norway, was confused when an adult sea walnut he was keeping in a laboratory tank, with its plump gelatinous lobes that define adulthood in this species, suddenly disappeared. In its place pulsed a larva, more walnut-shell-shaped than any adult of its kind.

He sensed the existing research might not be the full story, and so in collaboration with Michael Sars Center colleague, Pawel Burkhardt, set out to check whether this jelly had somehow pressed rewind on aging.

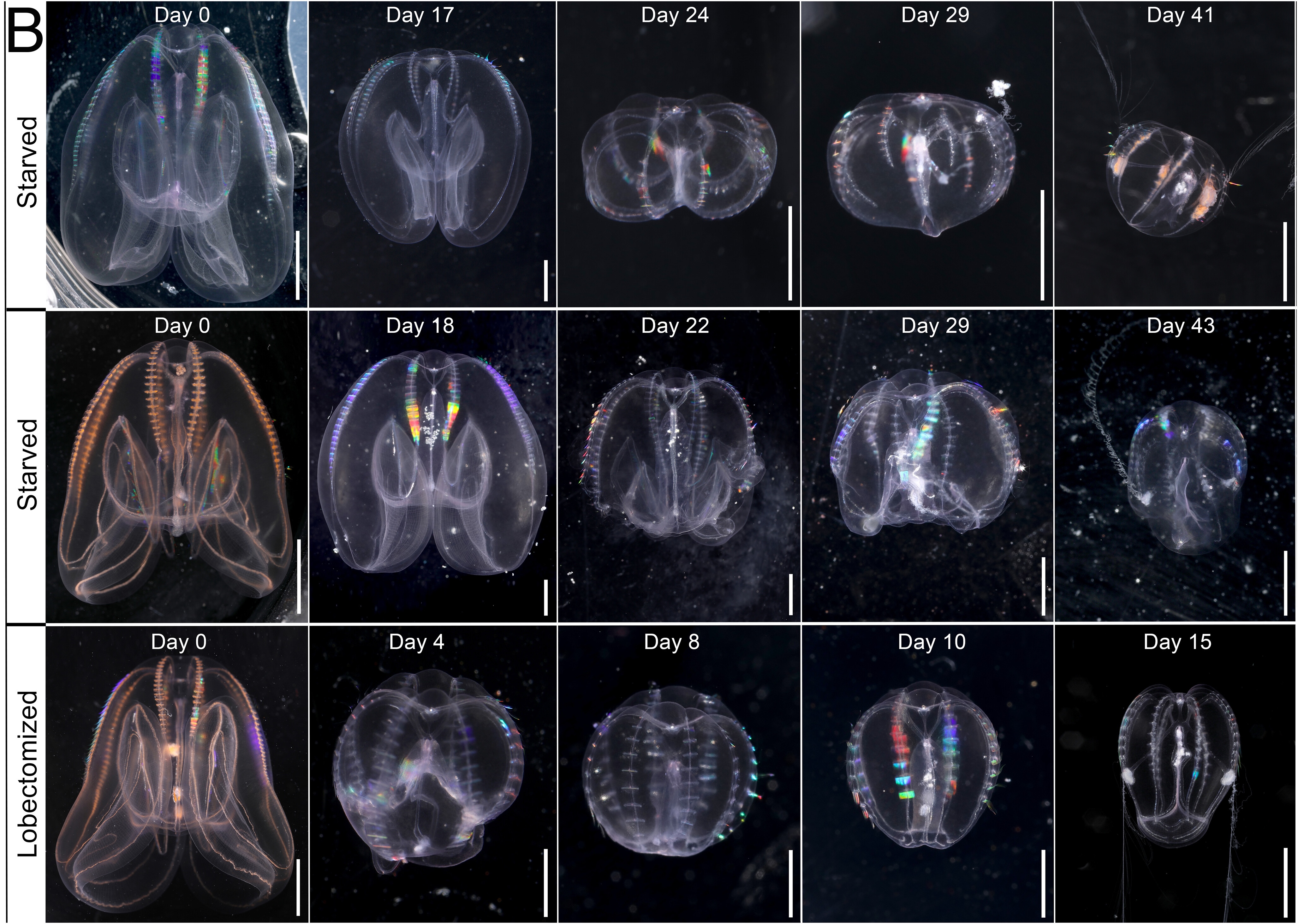

They kept 65 healthy adult comb jellies isolated in tanks, all of which had completely reabsorbed the tentacles of their youth, another defining feature of their maturity.

All were starved for 15 days, and then fed once a week with a small amount of rotifers, a much leaner diet than usual, and as expected, began to quickly shrink.

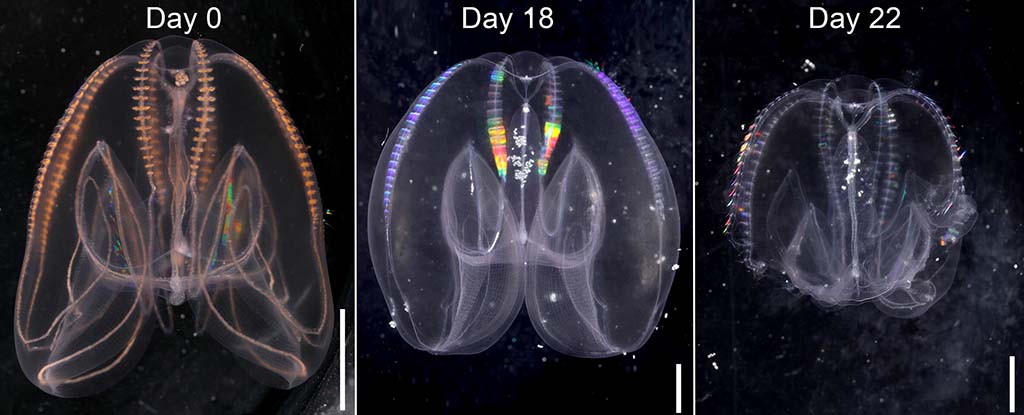

When their adult lobes began to ‘reabsorb’ into their diminishing bodies, feeding was resumed every second day. And Soto-Angel knew he was onto something.

Fifteen of these jellies also had lobes surgically removed at the start of the experiment, adding a further stressor that the previous experiments hadn’t captured.

“Over several weeks, they not only reshaped their morphological features, but also had a completely different feeding behavior, typical of a cydippid larva,” Soto-Angel says.

“Witnessing how they slowly transition to a typical cydippid larva, as if they were going back in time, was simply fascinating.”

The experiment showed the jellyfish could revert to a youthful form when stressed only by starvation, but this was far less common than in the lobectomy group: Only seven of the 50 starved jellies fully reverted, while six out of the fifteen injured animals were the jelly equivalent of ’17 again’.

This also means many of the juvenile jellies in experiments and records might not have been as youthful as they seemed.

“It will be interesting to reveal the molecular mechanism driving reverse development, and what happens to the animal’s nerve net during this process,” says collaborator Pawel Burkhardt, who is leading investigations into the evolutionary origins of neurons.

“The fact that we have found a new species that uses this peculiar ‘time-travel machine’ raises fascinating questions about how spread this capacity is across the animal tree of life,” Soto-Angel says.

This research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.