If you’ve got a high school yearbook you can flick through, you might find that the least attractive people run a slightly higher risk of living a comparatively shorter life, according to a new study.

Researchers in the US analyzed the fates of thousands of teenagers who graduated high school in the US in the late 1950s, to take a closer look at how looks might be linked to mortality risk.

It’s not implausible that features we find attractive might convey information about our state of health. Past research has identified links between our immune systems and ratings of beauty.

Yet there is scant evidence on whether people commonly regarded as attractive are any more likely to see a ripe old age.

“Little is known about the association between facial attractiveness and longevity,” write social scientist Connor Sheehan from Arizona State University and economist Daniel Hamermesh from the University of Texas at Austin in their published paper.

“But attractiveness may convey underlying health, and it systematically structures critical social stratification processes.”

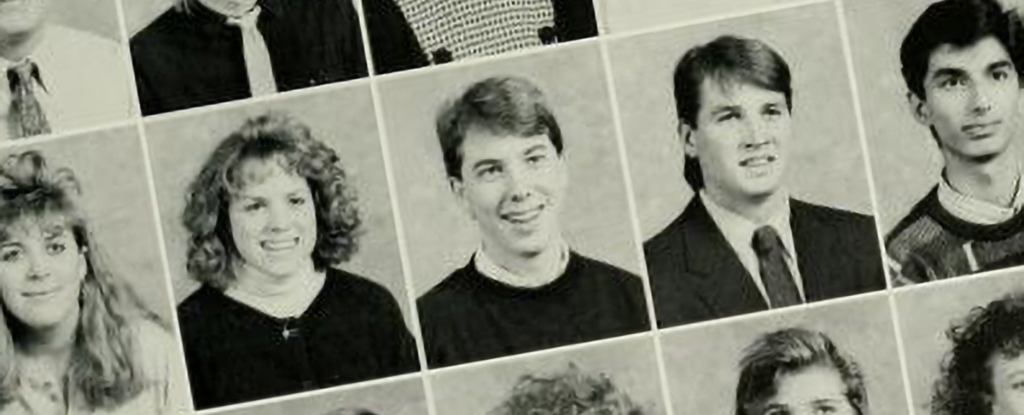

The researchers asked an independent panel of six male and six female judges to rank the attractiveness of 8,386 photographs taken of high school graduates in 1957 as part of the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study.

This beauty contest was then used to split the individuals into six different categories, rated from most attractive to least attractive.

Using the National Death Index, this was then compared with the deaths that occurred in the group up to 2022, by which time they were in their early 80s. Almost 43 percent of the people in the sample had passed away by the end of the follow-up period.

Those in the bottom sextile (or sixth) for attractiveness were some 16.8 percent more likely to have died than those in the middle four sextiles. However, the mortality rate difference between the middle four sextiles and the gorgeous-looking individuals in the top sextile wasn’t significant.

“Broadly, we found that those whose facial attractiveness was rated in the least attractive sextile had a higher mortality risk throughout life compared to those rated average or high,” Sheehan and Hamermesh write.

“Importantly, we found little advantage in longevity for those rated with high levels of attractiveness relative to the average.”

Accounting for factors such as education and earnings reduced the significance of the differences somewhat, with health being the most influential variable. This suggests, as you might expect, that in some cases, being in poor health and not looking great as a result could be playing a role.

The data here isn’t enough to prove direct cause and effect and is limited in that it focused on one geographical area, and the researchers acknowledge that the reasons for the association are unclear.

Nevertheless, it’s an interesting set of findings when it comes to looking after public health. Sheehan and Hamermesh are keen to see more research into the deeper connections at work linking health and disease with outward signs we can objectively measure over a lifetime.

“Social scientists should explore how attractiveness may influence still other processes that may contribute to its relationship to health and longevity,” write the authors.

The research has been published in Social Science & Medicine.