We stockpiled, considered building bunkers, and generally prepared for the first tech apocalypse on January 1, 2000, like it might be the end of the world. But the original Y2K came and went and was nothing compared to Y2K24.

That’s what many have come to call the CrowdStrike outage that sparked a global tech calamity on an unprecedented scale.

The particulars, as we understand them, are this: cybersecurity firm CloudStrike delivered a bad bit of code to Windows host systems around the world that led to those Windows systems and servers crashing and blue screening across the globe. CloudStrike has thousands of customers, many of them in business, enterprise, government, travel, health, and more… the list goes on.

Travel was upended, health providers couldn’t serve patients, banks were unavailable, stock markets closed, and shipments stalled. Everything basically went to hell for most of July 19th, a day that will go down in history as the worst IT outage ever and our Y2K24.

I didn’t make up that term.

A bit of me on @CNN this morning talking about the #CloudStrike outage pic.twitter.com/0tckiXxxujJuly 19, 2024

I spent most of Friday on TV explaining the outage and answering questions. Most revolved around how this could happen, but TV anchors were equally concerned with how we could prevent this from happening again.

The slow dawning recognition is that the interconnected world we thought we lived in 24 years ago is now real. We thought our globalized system with everything running on computers that had never been programmed to handle the change to the new millennium would doom us, but it turned out that we were missing one key ingredient: the cloud.

In 1999, there was no cloud computing with vast services being delivered to millions over the internet and often updated without knowledge, preparation, or consent.

Most business-level cloud services (sometimes known as Software as a Service or SaaS) do get consent and try to prepare clients. But when you’re trying to stay ahead of ever-changing threat factors, that can be difficult. Zero-day attacks mean you must deliver that update to clients now.

CloudStrike hasn’t fully revealed exactly what happened here and if this possibly bad code was security-related, or just a feature update. But there’s no question that this is the wake-up call we needed.

Our preparation for Y2K seemed almost silly in hindsight because virtually nothing happened. But here we are 24 hours after the biggest tech collapse in memory and some systems are still struggling to recover.

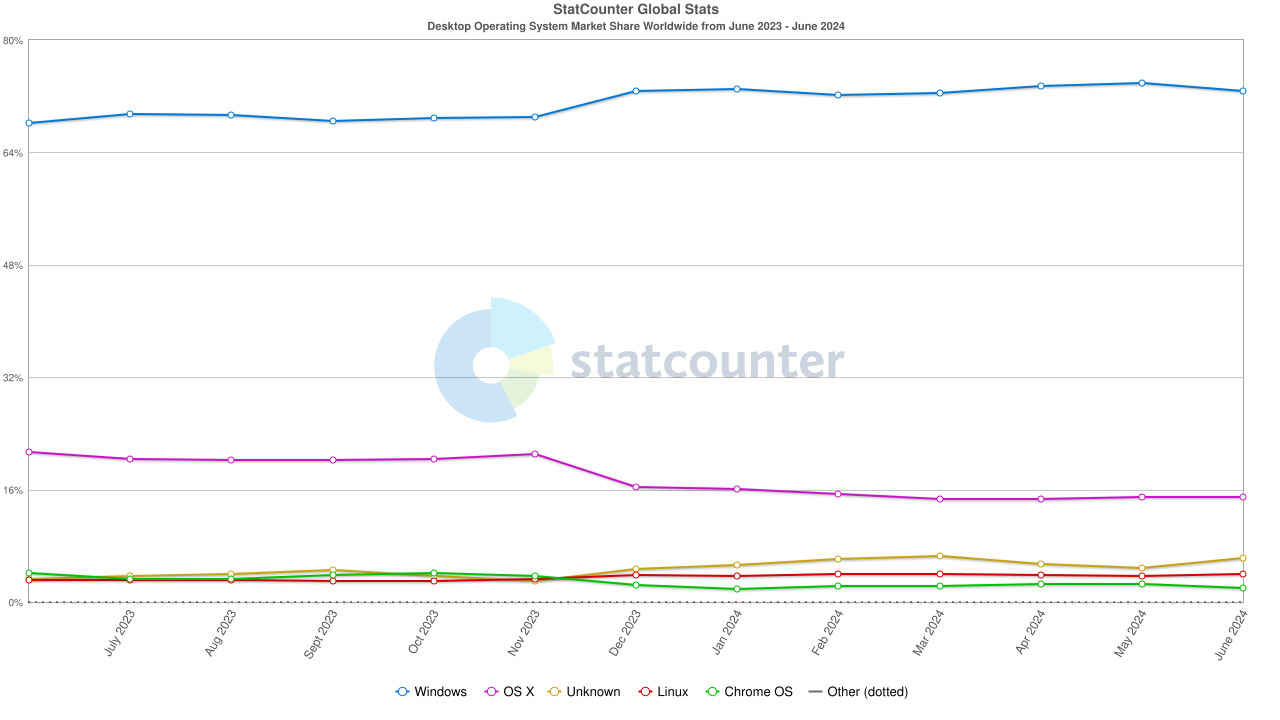

The roots of the global collapse are easy to trace. CloudStrike serves Windows host systems. Windows is still, by a wide margin, the most popular desktop OS (Statcounter has it at 72%). It’s like a global single point of failure. Windows had over 95% market share in 1998. It’s clear the missing component was a dominant cloud service with open-border code delivery to all those Windows systems (that not enough companies had sandboxes for incoming code is another issue).

If we don’t take mitigation steps now, like diversifying cloud-based providers beyond one dominant service, this will happen again. In some ways, we had a warning earlier this year when AT&T went down because of another code mistake. What’s worse is we saw how the knock-on effects can easily spread to other seemingly separate services.

In the case of CloudStrike, it cuts across so many industries that any time it has a significant failure, everything, and all of us are at risk.

Y2K was always real; it just took 24 years to arrive. I didn’t add this when talking to the anchors but maybe I should’ve: I have no idea how we prepare for the inevitable next global tech collapse.