A film shows a large group of children walking out of Auschwitz concentration camp in the company of nuns. Regina Horowitz recognized her own child and begged the camera operator to give her the frames of the film depicting Ryszard.

There are very few survivors left as the world commemorates the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi death camp Auschwitz. The Horowitz family’s tale of survival is one such documentation.

The Kraków orphanage would send her Regina Horowitz to another address, where she miraculously found her five-year-old son, who was just as shocked to see his mom alive. And not just her, but also his sister Niusia and his grandmother . . . all three women saved by German industrialist Oskar Schindler.

HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS CAN LIVE ON FOR GENERATIONS WITH CREATIVE USE OF NEW TECHNOLOGY

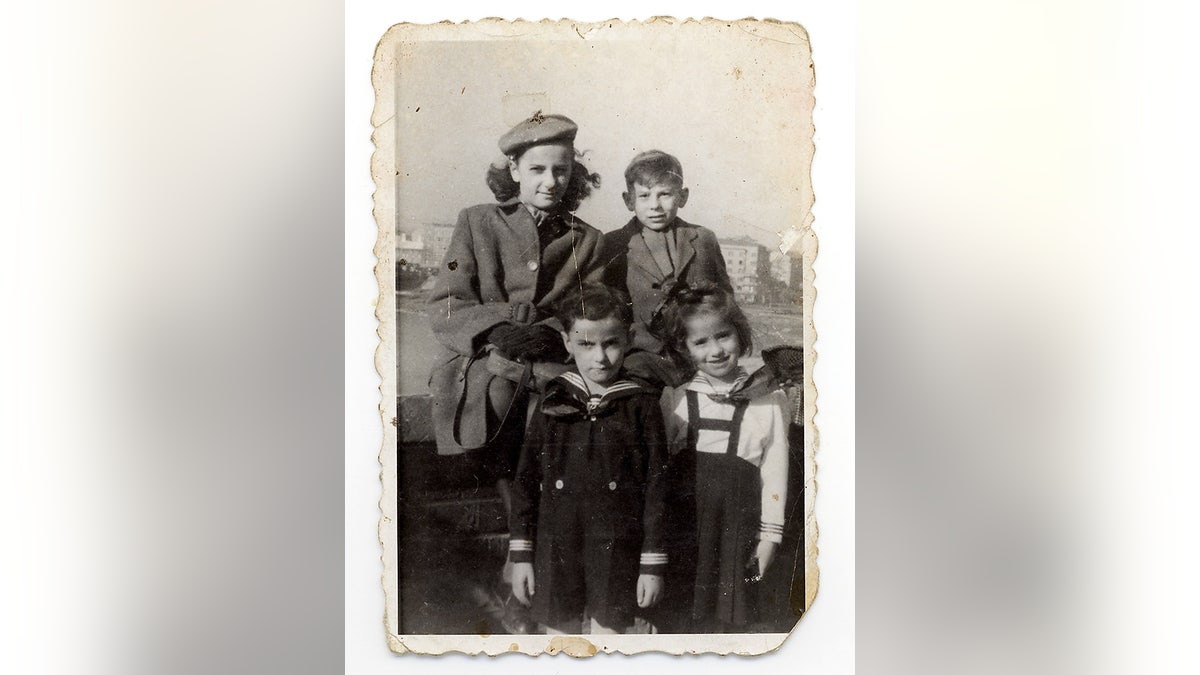

Ryszard Horowitz, Niusia Horowitz-Karakulska and Roman Polanski enjoying a day at Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków, with Roman’s uncle. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz )

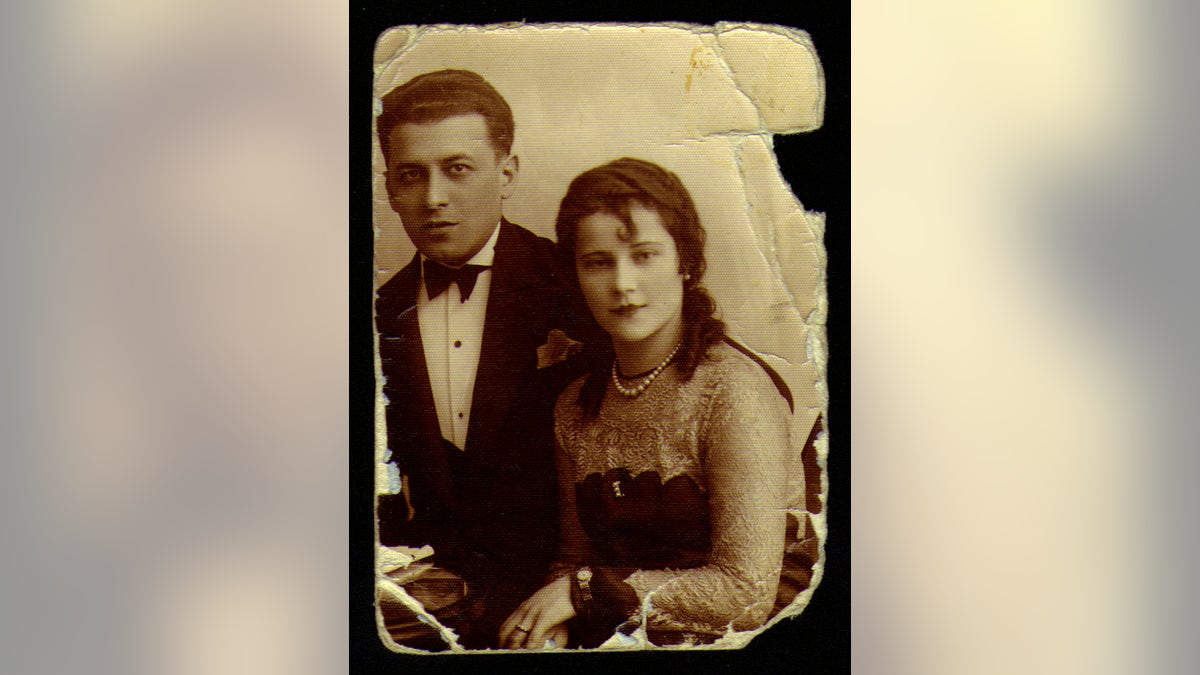

Renowned photographer Ryszard Horowitz was born on May 5th, 1939, to a loving family in the historic city of Kraków, the former capital of Poland, but just four months later Nazi Germany invaded Poland, resulting in utter devastation.

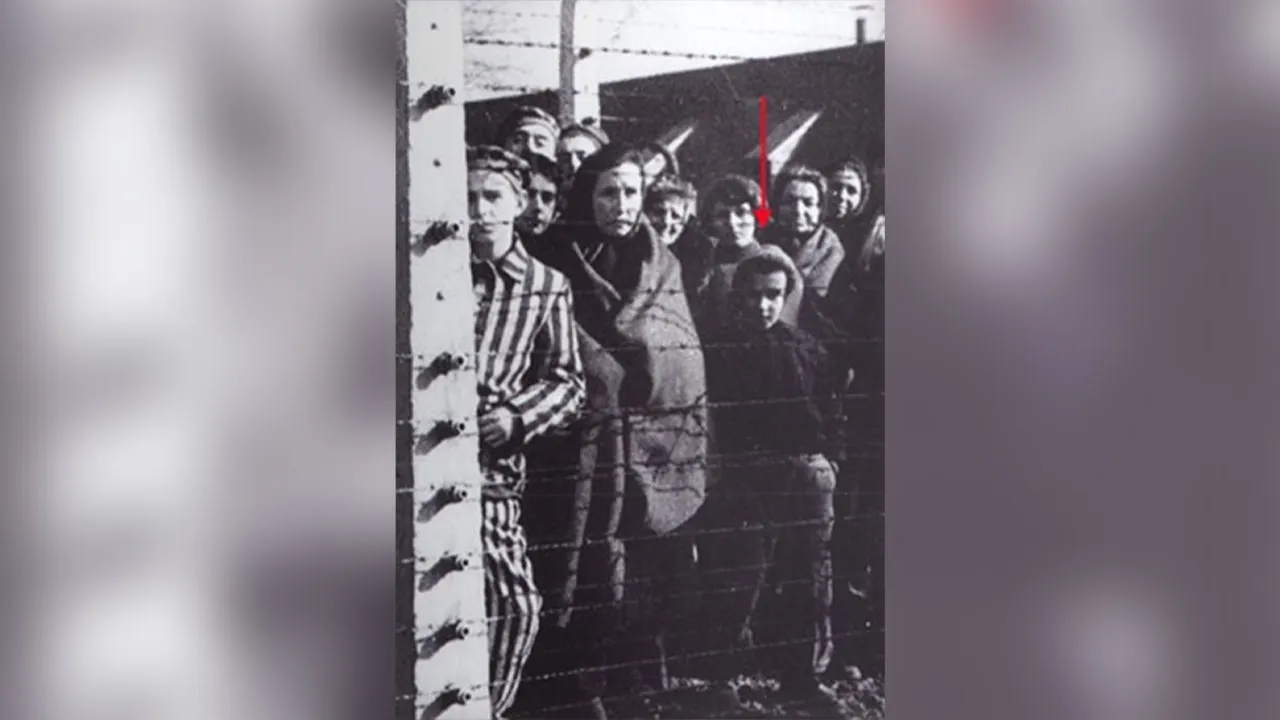

Ryszard Horowitz, highlighted, behind the barbed wire of Auschwitz Concentration Camp, Liberation of the camp in 1945. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz )

The war would turn brutal and sinister, especially for Poland’s Jews.

“When the Germans marched into Kraków,” Horowitz told Fox News Digital, “my parents’ first reaction was to run away. They packed their suitcases and left me with my non-Jewish nanny, Antosia. But soon they returned with my sister, because they did not want me to stay behind. So, we were reunited but eventually forced to relocate to the ghetto.”

Dawid and Regina Horowitz, wedding photo. Kraków, 1932. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz )

The Nazis segregated Jews from the rest of the population, forcing them into Krakow’s notorious ghetto. Life was bleak behind the fences, in constant fear of Nazi persecution.

Kraków Ghetto, gate one, 1941. Photo from the collection of The Historical Museum of the City of Kraków, Poland.

Fortunately for Ryszard, there was an older boy there, called Roman Liebling, known later as Roman Polanski, who attended his third birthday party. According to Polanski, although food was scarce, by some miracle Ryszard’s mother, Regina, managed to procure hot chocolate for the kids. Ryszard, however, did not care for hot chocolate and refused to drink it.

Niusia Horowitz, Roman Polanski, Ryszard Horowitz, Roma Ligocka in Kraków, 1946. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

By 1943, the Germans were liquidating Kraków’s ghetto, and the Horowitz family was forced to relocate to a Nazi concentration camp in Plaszow. It was run by a notorious Nazi commander, Austrian officer Amon Göth.

The remnants of a wall from the Jewish ghetto in Krakow, Poland. January 11, 2023. (Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

“It was a terrible camp, because the man in charge was an extremely brutal character. He created a tremendous sense of fear. He was shooting people right and left. He was like a God in terms of his power and made life there totally impossible,” Horowitz recalled.

Göth liked to throw parties in his villa, where two of Ryszard’s musician uncles were forced to play.

Ryszard Horowitz’s uncles had careers as entertainers before World War Two began. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

One of the men attending the parties was German industrialist Oskar Schindler. His friendship with Göth enabled him to run a business that would ultimately become a lifeline for many of the camps Jews.

“Oscar Schindler got permission to open a factory producing utensils for the German army, and my family worked there.” Horowitz explained.

Steven Spielberg, Ryszard Horowitz, Ania Bogusz and Bronisława Horowitz-Karakulska. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

Steven Spielberg introduced Oskar Schindler to the entire world in his 1993 movie “Schindler’s List,” and Horowitz shared some observations about the famed businessman.

“Everybody will tell you something else about him. How good he was, how bad he was, how handsome he was, how many women he had, but the bottom line is . . . somehow, he felt this urge to save people. Once, he got into trouble when he kissed my sister when she gave him a cake for his birthday,” Horowitz said.

In 1944, the Germans decided it was time to dismantle Plaszow, disguise the traces of their atrocities, and close Schindler’s factory.

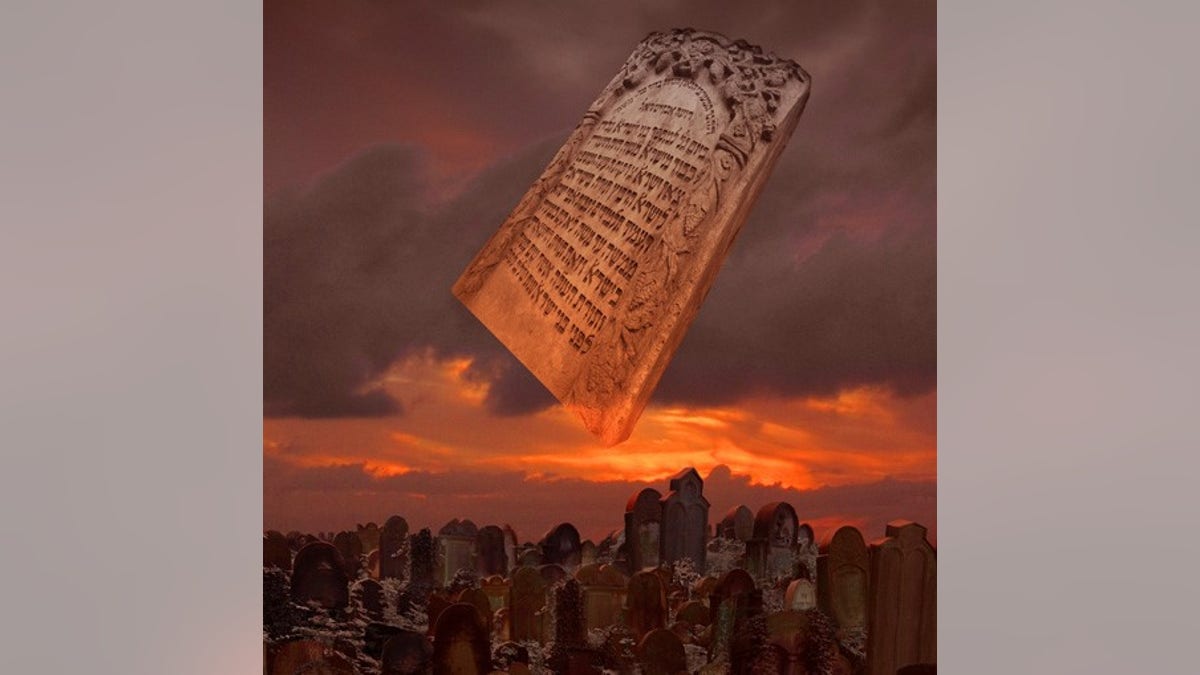

The Jewish Cemetery in Kraków, photocomposition by Ryszard Horowitz. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

“Schindler managed to get permission to move a certain number of workers to his factory in Brünnlitz, in Czechoslovakia,” Horowitz said.

Brünnlitz was a German labor camp, and as Spielberg showed in his film, a list was created with names of those who would be relocated there.

“There is no question that there was a list, and my family was on that list. I was not, because I was too small to work, but somehow, I managed to squeeze in. There were two transports, one of men and one of women. I was traveling with my father,” Horowitz explained.

Schindler’s men made it to Brünnlitz alive, but Ryszard’s life was about to unravel.

“We waited for the women to follow us to Brünnlitz. But, for some reason, we do not know why, they were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp instead,” he said.

Schindler hurried to Auschwitz to rescue his women and left Josef Leipold in charge of his factory.

“Leipold was the exact opposite of Schindler.” Horowitz said. “From the beginning, his idea was to finish us off. And he did not want children there. So, he packed us with our fathers and shipped us to Auschwitz.”

Upon arriving at Auschwitz, Ryszard was selected to have concentration camp numbers tattooed on his forearm. Which meant he would stay alive, for a time.

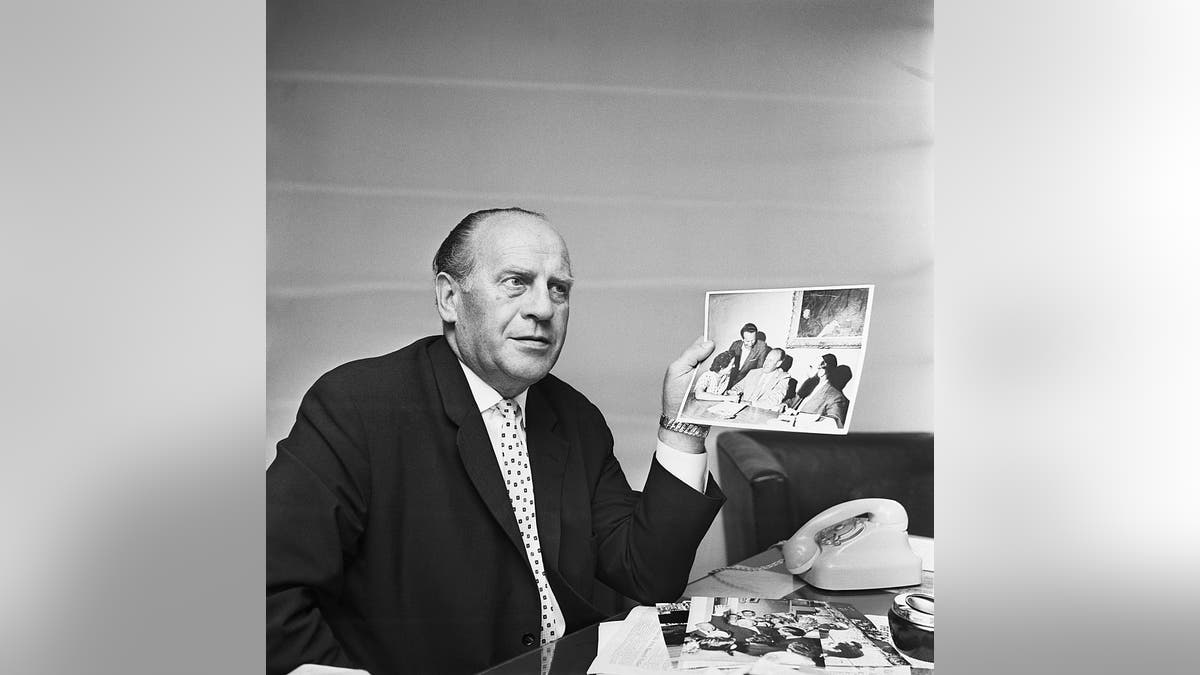

Businessman Oskar Schindler speaks about saving lives during the Holocaust of Germany’s Third Reich in an interview with United Press International. (Bettmann / Contributor/Getty Images)

YOUNGEST PERSON SAVED BY OSKAR SCHINDLER: ‘I FEEL GUILTY THAT I SURVIVED’

Oskar Schindler managed to rescue the women. They were aboard a train that was about to depart for Auschwitz.

Horowitz recalled these heartbreaking moments, “My cousin and I saw the train, and my mother was there, my sister, my grandmother . . . and they saw us. My mother was certain this was the last time she would see me. They went to Brünnlitz, and my father and I remained in Auschwitz.”

In January 1945, with the Red Army approaching, German SS forces marched thousands of prisoners out of Auschwitz to different camps on German territory. Richard’s father, Dawid “Dolek” Horowitz, was forced to leave his son behind.

“I think that one of the reasons I survived was that a man in charge of a warehouse, Roman Gunz, agreed to look after me. Sometimes he would feed me, and when things got difficult, he would hide me in the warehouse or inside the infectious hospital ward,” Horowitz said.

Then one day, the nightmare of Auschwitz came to an end.

“When the Red Army came close to the camp, the Germans were in a panic. They rounded all the kids up and were ready to shoot us, but just then two German officers arrived on motorcycles screaming to drop everything and follow them, so they did,” Horowitz remembered.

A few hours later, Soviet troops entered Auschwitz.

“The Red Army arrived, most of them on horseback,” he said. “They gave us food and sweets. They had cameras with them, and they recorded a lot of footage. The following day, nuns arrived and took us to an orphanage in Kraków. Polanski’s aunt Tosia found me there and took me to her apartment on Dluga Street. And Roman was already there.”

The Horowitz Family survivors, Szachne, Sabina, Niusia, Regina, Ryszard and Dawid. Kraków, Poland. (Ryszard Horowitz)

In March 1945, Brünnlitz was liberated, and the Horowitz women returned to Kraków.

“One day, my mom was out in the market Square, where they were showing a documentary movie about the liberation of Auschwitz, and she recognized me in it,” Horowitz said.

The Horowitz women moved in with Roman Polanski’s family. They were soon joined by Dawid Horowitz.

“We all lived under one roof for two years, until my father got us a nice apartment near Market Square,” Horowitz said.

After the war, Poles found their country in ruins with a hostile communist regime in charge.

“Most of my closest friends and their families were anti-communists. Everybody’s dream was to get out of Poland as fast as possible,” Horowitz explained.

Regina and Dawid Horowitz reunite with Oskar Schindler and Henry Rosner in Vienna. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

Dawid Horowitz managed to open a store selling tools and building materials, with Polanski’s aunt Tosia as his business partner. Life went on.

“For me and my friends, life was pretty good at the time, because we were not engaged in politics. We were artists, and we believed that we lived in a totally free society, so we did what we wanted to do, and we had this amazing outlet, a cabaret called “Piwnica pod Barnami” (The Cellar under the Rams). And we had jazz,” Horowitz recalled.

Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond, in Kraków,1958. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

In 1958, American jazz pianist Dave Brubeck arrived in Kraków to perform. Ryszard Horowitz was there with his camera and documented it in pictures. Little did he know that photography was his future. And that future was on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Ryszard Horowitz, aboard the Polish ocean liner “MS Batory,” departing for America in 1959. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

“I had this opportunity because my uncles here in New York were ready to offer me room and board. And I also received a scholarship from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn,” Horowitz said.

With his father’s encouragement and some U.S. dollars hidden in the heel of his shoe, Horowitz boarded the Polish ocean liner “MS Batory.”

Life as an immigrant in the Big Apple was a mixed bag. But at the Pratt Institute, Horowitz quickly exhibited a unique talent for photography.

Ryszard Horowitz photo shoot for Tiffany & Co. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

“I created their first photography lab at Pratt, and I was asked to design their 75th anniversary yearbook, which I edited, and I pretty much took all the photographs for them. It was the first time in history that the New York Art Directors Club gave an award to a student. So, this became my portfolio,” Horowitz explained.

Photocomposer Ryszard Horowitz: One-Man show in Beijing, China. (Ryszard Horowitz)

Ryszard connected with influential people who helped pave his way to success. Among them were photographer Richard Avedon, graphic artist Saul Steinberg and ballet choreographer Sergei Diaghilev, as well as his idol, disc jockey Willis Conover, who hosted the Jazz Hour on the Voice of America.

Through the lens of his camera, Horowitz saw the world somewhat differently. His photographs looked like computer-generated graphics, except that they predated the digital age. He became known as the pioneer of special effects photography.

FULL-SCALE REPLICA OF ANNE FRANK’S HIDDEN ANNEX TO BE UNVEILED IN NEW YORK CITY

“I found a way of reversing perspective and juxtaposing large objects to make them look small and vice versa,” Horowitz said.

Horowitz was a master of light. He learned to manipulate light to photograph expensive jewelry and new cars.

“My art education in Kraków helped me – my devotion to the great masters of painting,” Horowitz explained.

Ryszard Horowitz receives an honorary doctorate at the University of Warsaw, Poland. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

His iconic commercial work captivated audiences in the world of advertising, bringing him fame and prestigious awards. He received honorary doctorates from the University of Warsaw and Wrocław in Poland, and in 2014, his hometown of Kraków made him an honorary citizen.

“Some of my photographs consist of different images taken in different parts of the world, and they are merged into a single unit that’s not jarring but believable. They appear as though they are an instance of a situation that never existed except in my head. That’s why I call myself a ‘photocomposer,” Horowitz explained.

Award-winning digital photo-composition: Allegory (1992) by Ryszard Horowitz. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz. (Ryszard Horowitz)

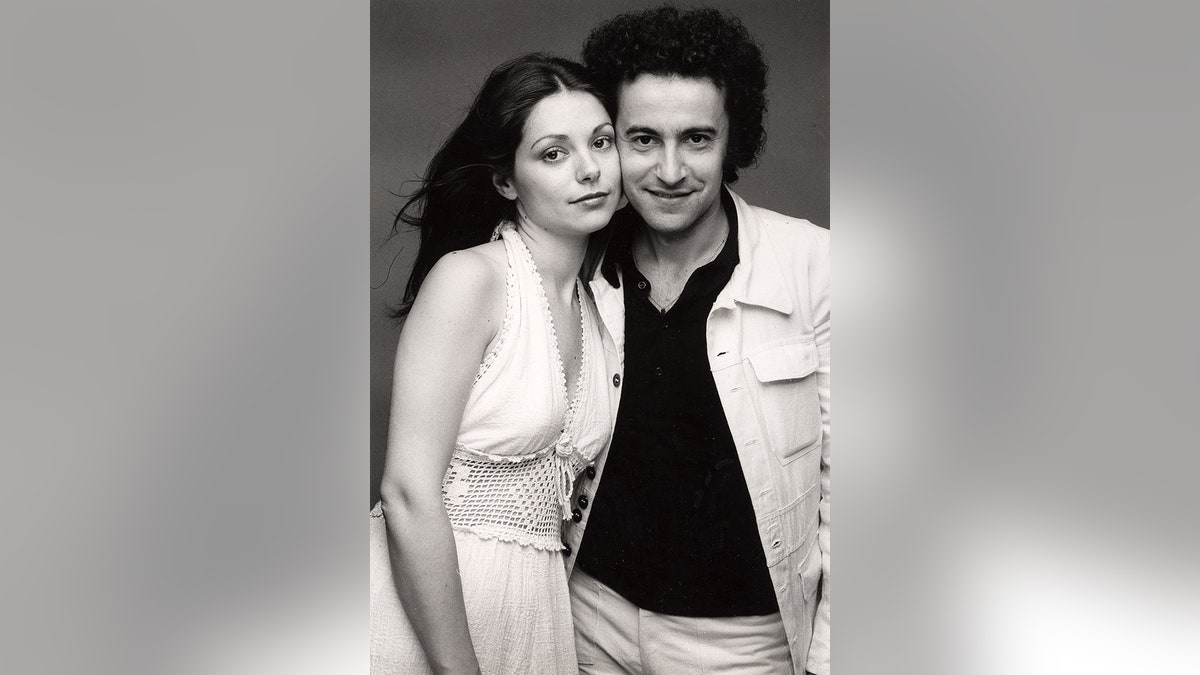

He achieved success in his personal life as well. Since 1974, he’s been happily married to Anna Bogusz, and they have two grown sons: Daniel and Emil.

Emil, Ania and Daniel Horowitz. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“I met Ania at a party. She was an architecture student from a Polish family living in Caracas, Venezuela. She was only passing through New York on her way to Paris to continue her studies. She never made it to Paris,” Horowitz smiled, recollecting meeting the love of his life.

Ania Bogusz and Ryszard Horowitz, 1974. Photo courtesy Ryszard Horowitz.

So many years after he walked out of Auschwitz alive, Ryszard Horowitz feels blessed to live the American Dream with his family, and doing what he loves most – creating his photo compositions . . . and listening to jazz.