An investigation into nearly 1,700 aquifers across more than 40 countries found that groundwater levels in almost half have fallen since 2000. Only about 7 percent of the aquifers surveyed had groundwater levels that rose over that same time period.

The new study is one of the first to compile data from monitoring wells around the world to try and construct a global picture of groundwater levels in fine detail.

The declines were most apparent in regions with dry climates and a lot of land cultivated for agriculture, including California’s Central Valley and the High Plains region in the United States. The researchers also found large areas of sharply falling groundwater in Iran.

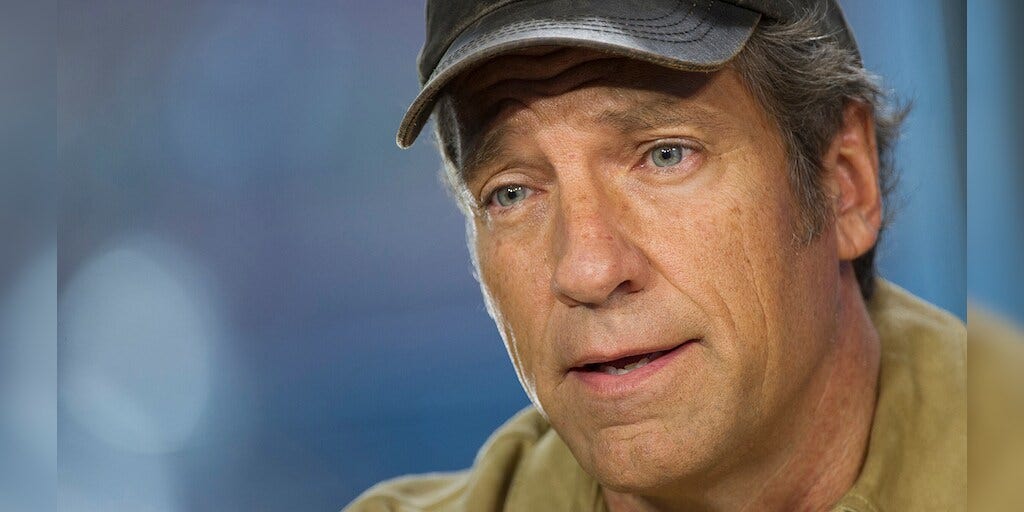

“Groundwater declines have consequences,” said Scott Jasechko, an associate professor at the University of California Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, and the study’s lead author. “Those consequences can include causing streams to leak, lands to sink, seawater to contaminate coastal aquifers, and wells to run dry.”

Past global studies have relied on satellite observations with much coarser resolution, and on models that calculate groundwater levels rather than directly measuring them.

The research, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, confirms widespread groundwater declines previously found with satellites and models, said Marc Bierkens, a professor of hydrology at Utrecht University who was not involved in the research. The paper also offers new findings about aquifers in recovery, he said.

The researchers compared water levels from 2000-20 with trends from 1980-2000 in about 500 aquifers. This comparison to an earlier era revealed a more hopeful picture than just looking at water levels since 2000. In 30 percent of the smaller group of aquifers, groundwater levels have fallen faster since 2000 than they did over the earlier two decades. But in 20 percent of them, groundwater declines have slowed down compared to earlier and in another 16 percent, trends have reversed entirely and groundwater levels are now rising.

The improvements are happening in aquifers around the globe, in places as diverse as Australia, China, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Spain, Thailand and the United States. These aquifers provide reason for cautious optimism, said Debra Perrone, an associate professor at the University of California Santa Barbara’s Environmental Studies Program and co-author of the new research.

“We can be optimistic in that our data reveal more than 100 aquifers where groundwater level declines have slowed, stopped or reversed. But cautious in that groundwater levels are rising at rates much smaller than they are declining,” she said. “It’s much easier to make things worse than to make things better.”

The study relies on data from about 170,000 monitoring wells that government agencies and researchers use to track the water table. Well data is not available or does not cover enough years everywhere, so the researchers were limited to studying aquifers in about 40 countries and territories.

A recent New York Times investigation analyzing more than 80,000 monitoring wells in the United States found broadly similar trends within the country.

The causes of groundwater decline differ from place to place. Some big cities rely on groundwater for household use. Outside of cities, irrigation for agriculture tends to be the biggest user of groundwater.

“It would not surprise me if many of the trends that we see globally are at least in part related to groundwater-fed irrigated agriculture,” Dr. Jasechko said.

One common correlation the researchers identified was a change in the amount of rain or snow falling over a region. In 80 percent of the aquifers where groundwater declines accelerated, precipitation also decreased over the 40-year time period.

Where aquifers are recovering, the causes vary. In some places, like Bangkok and the Coachella Valley of California, governments have created regulations and programs to reduce groundwater use. In others, like several areas of the Southwest United States, communities are diverting more water from rivers instead. In the Avra Valley of Arizona, officials are actively recharging their aquifer with water from the Colorado River, a water body facing pressures of its own. In Spain, water managers are recharging the Los Arenales aquifer using a combination of river water, reclaimed wastewater and runoff from rooftops.

A valuable contribution of this new research is pinpointing local distinctions, where data from wells on the ground diverge from larger regional trends that satellites can identify, said Donald John MacAllister, a hydrogeologist at the British Geological Survey who reviewed the paper.

“What we often hear is groundwater decline is just happening everywhere. And actually, the picture is much more nuanced than that,” he said. “We need to learn lessons from places where things are maybe slightly more optimistic.”